Unknown

Authors: Unknown

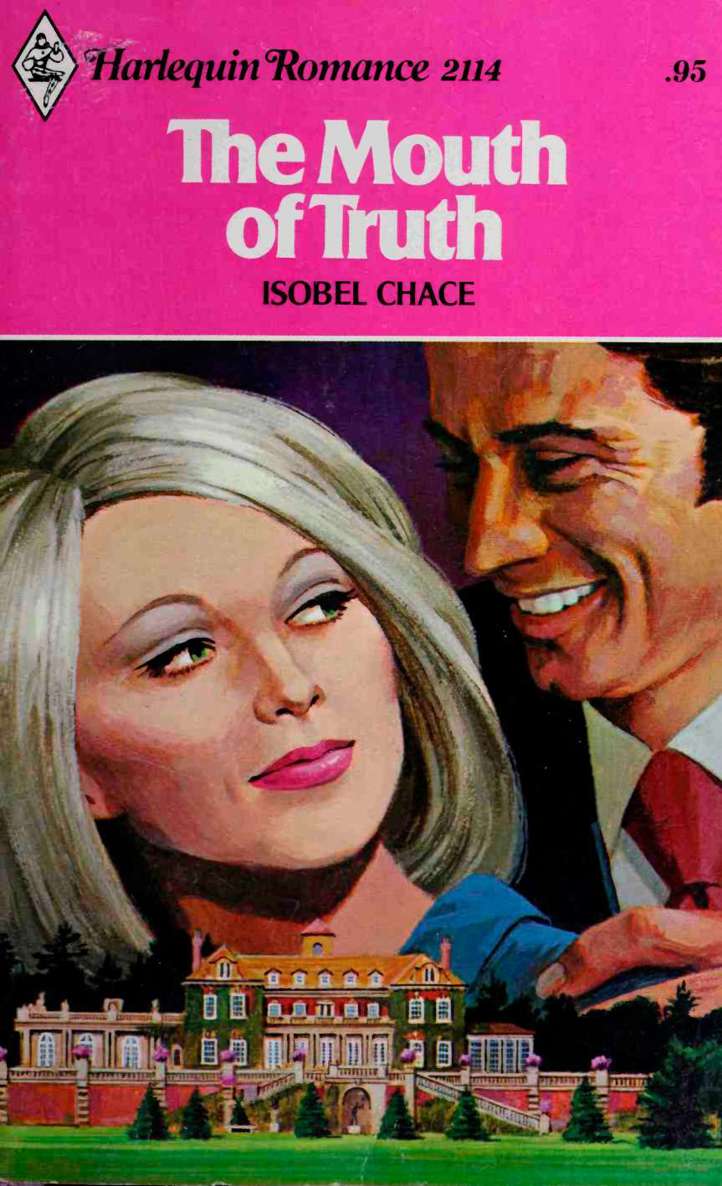

THE MOUTH OF TRUTH

Isobel Chace

Domenico Manzu was like no one else she had ever met, and Deborah hadn't the remotest idea how to cope with him.

If she'd heeded her father's warning, she'd never have come to Rome. Now, here she was, virtually kidnapped, yet treated like a guest.

Domenico was a very charming villain. But Debbie knew that while he had captured her person, she'd be a fool if she allowed him to capture her heart! Yet, ridiculous as it was, she wanted to stay....

Original hardcover edition published in 1977

by Mills & Boon Limited

ISBN 0-373-02114-3

Harlequin edition published November 1977

Copyright © 1977 by Isobel Chace.

All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in whole or in part in any form by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, is forbidden without the permission of the publisher. All the characters in this book have no existence outside the imagination of the author and have no relation whatsoever to anyone bearing, the same name or names. They are not even distantly inspired by any individual known or unknown to the author, and all the incidents are pure invention. The Harlequin trademark, consisting of the word HARLEQUIN and the portrayal of a Harlequin, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in the Canada Trade Marks Office.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

The

stranger who was also her father looked disapprovingly at her across the huge double desk.

'Your mother tells me you are going to Rome,' he said at last.

Deborah nodded. It was so long since she had seen him that she was fascinated to try and find some familiar ground between them. Looking at his strong, essentially cold features, she could find none. He didn't feel like her father at all.

'With friends?' he prompted her.

'Of course with friends!' she responded immediately. 'You didn't suppose I was going on my own, did you? There's a whole crowd of us going.'

'Hmm. It's not the place I'd choose for you at the moment. We have large business interests in Italy '

'Have you?' She was only marginally interested. 'But what has that got to do with me?'

'As my daughter '

Deborah shrugged. 'Do you really think of me like that?' she demanded, knowing the answer with a depressing certainty even before she voiced the question.

'Of course,' he murmured. His face took on a shine of embarrassment. 'I may not have seen much of you in past years, Deborah, but that was not of my choosing. You bear my name, after all, and who else do you suppose has paid your bills all these years?'

Yes, they shared a name, but there had to be more than that, she thought. Was there nothing else between them but a name and a few bills marked paid with thanks?

'I wish we knew each other better,' she said aloud.

'Quite. Perhaps this holiday of yours is the moment for doing so. Why don't you come and stay at our house for a while? Agnes would be pleased to put on some parties for you with people of your own age. You wouldn't be dull with us!'

It was her turn to feel awkward. 'I'd rather not,' she said honestly. She had only met Agnes once, but she had no wish to repeat the experience. 'What have you got against Rome?'

Her father leaned back in his chair. 'Sometimes I think your mother has never got over a childish desire to upset me! I suppose it was she who put this idea into your head?'

'Mother? I don't think so. All she said was that you wouldn't like it and that I'd better talk it over with you myself, because she wasn't going to do your dirty work for you yet again. So what's wrong with Rome?'

Her father sighed. 'The company has been having a lot of bad publicity in Italy these last few weeks, if you must know. I don't like the thought of your being there on your own '

'But I won't

be

on my own! I'll be with friends!'

'Beside the point, my dear. There won't be anyone there who knows who you are to protect you.'

'Protect

me? Whatever from?'

Her father looked grim. 'From the enemies of the company. You're not paying attention, Debbie! I've already told you we have large business interests in Italy.'

'But they're nothing to do with me!' she said. 'Are they?'

'You're my daughter.'

'Yes, but hardly.' She hoped he wouldn't think she was trying to be rude to him, but he must know that he scarcely felt like a father to her at all. 'None of my friends connect me with you,' she added.

'Don't they know you as Deborah Beaumont?'

'Well, yes, of course they do! But there are hundreds of Beaumonts, after all, and I don't go round boasting that my father is Beaumont's International. Why should I?'

Her father was silent for a long moment. 'You should be proud of Beaumont's,' he said at last. 'It's my life's achievement.'

But one didn't feel proud of something one knew nothing about. However, she recognised the hopelessness of explaining that, or anything like it, to him, and settled instead for a vivid description of the kind of holiday she had in mind.

'It's got nothing to do with business,' she said gently, trying hard not to offend him further. 'And certainly it's got nothing to do with Beaumont's. I'm going to Rome with five friends of mine, none of whom have any money at all, living in the cheapest lodgings we can find—you know the sort of thing. You wouldn't consider it a holiday at all!'

'Probably not.' Her father managed a tired smile. 'And do you intend to wear the kind of garments you have on now? You'll never get into the Vatican dressed like that!'

Deborah looked down at her jeans and sweater with a little frown. 'I'll be taking a dress with me too. I'd have put one on today to come and see you, but your summons rather took me by surprise. You've never insisted on my visiting you here before, have you? I wish you'd tell me what you're afraid might happen to me in Rome instead of muttering about Beaumont's. It must be more than that you don't think my clothes do credit to the firm?'

'My dear Deborah, I'm not totally out of touch with what young people think and wear these days '

Belatedly, Deborah remembered that he had other children and that though they had Agnes for a mother, an ex-model who had never been seen by anyone including, she suspected, her husband, with a single hair out of place, they probably also wore jeans on occasion.

'No, of course not!' she agreed dutifully.

'Beaumont's has had a very bad time in the Italian Press recently. One would think we'd been infiltrated by the CIA at least, and even the most ordinary business methods have suddenly become suspect. There was a small incident where we were accused of helping a certain politician into power '

'And did you?'

Mr Beaumont winced. 'I hope not, but it seems likely that we did. It was a good opportunity for getting several contracts for the company—but these things are better done with a certain panache or not at all. If you bungle a thing like that you're asking for trouble!'

'And you got it?'

'We got a great deal of adverse publicity, but we could have weathered that easily enough. No, the worst part of it all was an inquiry into our finances—our

personal

finances, you understand, and certain people in the firm were found to be much better off than anyone had supposed.'

'Including the tax office?' she suggested with only a touch of malice.

'In Italy everyone is in arrears with their taxes. Most people refuse to pay them at all! At least we don't do that!'

Deborah laughed. 'Are you much richer than we all thought?'

Her father did not share her amusement. 'I have no intention of discussing my finances with you, young lady! All I'm saying is that you might be recognised as my daughter while you are in Italy and the results could be extremely harassing for both of us. Won't you change your mind and stay at home this year, Deborah?'

Deborah rose to her feet, feeling a little sorry for the tight-lipped man on the other side of the desk.

'I'm sorry, Father. I want to go and I'm going, but don't worry about it. If anything happens to me, I'll deny any connection between us with my dying breath, so there won't be any comeback on you. Okay?'

'I don't believe you've thought this thing through properly '

'Probably not,' Deborah agreed gently. 'I'm sorry, Father, but I really can't take it very seriously. All I want to do is have a look at Rome with my friends. Is that really going to bring ruin on your life's work?'

'Let's hope not,' he grunted. 'I'll have to let them know you're coming, that's all. They'll have to deal with it at their end!'

Deborah chewed on the inside of her lip. 'Father, I don't want to be bothered with Beaumont's while I'm away. Can't you understand that it doesn't mean anything to me? It isn't

my

life's work!'

'You're my daughter. Beaumont's may not mean anything to you, but they paid for your schooling '

'So what, Father?'

'You owe me and the firm some gratitude for that, surely?'

Deborah stared at him. 'Do you grudge what I cost you?' she demanded, now as angry as he.

'Of course not, but I am your father and I think you should listen to my advice, especially when I'm only thinking of your own good.'

'Are you?' Her mother would have recognised the light of battle in her sea-green eyes at once, but her father was less observant and knew her less well. 'Aren't you thinking of the firm?'

'It's the same thing, my dear,' he protested. 'Beaumont's supports us all—your mother as well as yourself, I may point out!'

'My mother is supported by you, I agree,' she said slowly and clearly, 'but I am not. You bought Agnes, and maybe you can buy your other children, but you won't buy me! Goodbye, Father. I'll send you a card from Rome!'

'Deborah!'

She had, she supposed, been unpardonably rude, but she didn't care. She walked out the door, slamming it behind her, nodding to her father's surprised secretary as she went. She was burning with rage, and with humiliation too. What kind of person did he think she was? Some puppet who could be controlled by pulling the strings like he did with everyone else? Well, she was not! And if she had to go to Rome to prove her point to him once and for all, then to Rome she would go!

The plane was completely full as most charter flights are. Not for the first time, Deborah wished that her friends could have had their luggage pared down to a ruthless minimum by her mother as had happened to her. Even though Michael Doyle had insisted she should take the window-seat, he had then proceeded to load her up with packages, his friendly, sheepish grin effectively destroying any protest she might have made.

'Only the rich have suitcases to be stowed neatly away in the luggage hold,' he said. 'You shouldn't mix with the idle poor and then these little inconveniences wouldn't happen to you.'

Deborah was used to being teased about her riches. Once or twice she had explained that they were her mother's riches rather than hers and that she was no richer than anyone else, but she had to admit that most of her friends weren't even rich by association and, she supposed, if the worst ever came to the worst, she had the comfortable knowledge that she would be rescued from her plight while they had no such assurance. Michael certainly hadn't. She had never even heard that he had any relatives. He was always on his own and would be now if she had not come along and taken him in tow. He was the cleverest person she knew. His intelligence shone out of his thin, bony face and knotted his digestion whenever she relaxed her vigilance over his diet, which wasn't often these days because she, who had never suffered a twinge of indigestion in her life, found his patient suffering in the face of chronic heartburn more than she could bear.

Michael made stained-glass windows for a hobby. He had sold some recently and it was that which had enabled him to come to Rome.

'I want to study the churches,' he had said.

'The stained glass too?' she had asked him.

He had shaken his head. 'Not their tradition, thanks be to God. They distract me from all the other things I want to see in France, where it's their tradition. I hope I don't see a single coloured window in the whole of Rome!'

Deborah didn't much mind either way. 'I'm glad we're going together,' she had said, and she had kissed him with rather more enthusiasm than she had actually felt because somehow everybody always paired her off with Michael and, if he was the best and most romantic thing in her life, she thought she should do something to encourage him.

Her other friends who made up their particular party had paired off long before she and Michael had come on the scene. John and Mary were both nice and blessedly unexciting. Patty had a kittenish prettiness and was quite the most selfish person Deborah had ever known and, therefore, perhaps it was only just that Jerry, dark, moody, and motivated by a spiteful envy of anyone better off than himself, should have caught her attention, for if anyone could stand up to her exclusive interest in herself and her own affairs it was he.