Until I Say Good-Bye (10 page)

Read Until I Say Good-Bye Online

Authors: Susan Spencer-Wendel

A

fter the party, with kids back in school and John back at work, I gave myself another gift. One based more on want than necessity: permanent makeup.

I love fashion, always have and always will. I was no beauty queen, but I always prided myself on being well put together. Perhaps a form-fitting black dressânot too tight or too short for work. And black heels, four inches, closed toe, a thick heel to signal “not stripper shoes.”

Ah, heels, love them. Wore them every day of my adult life, even nine months pregnant. With bunions. Then my legs became too weak. Out went the high heels.

No way was I letting that happen with makeup.

Makeup was my friend. It opened my beady eyes, created cheekbones where none existed, transformed my gullet gateway into kissable lips.

Makeup is precise, an art of millimeters. Fine lines erased around eyes, shadowsâsometimes three shadesâapplied just so on eyelids and under brows, with a dot of sparkly white on the brow bone to open the eyes and make a twinkle.

Like so many women, I had spent scads of money finding the just-so combo for my face. Found a lip color I lovedâRaisin Rageâa shade of plum that looked natural and nice. Wore it every day.

Lined my beady eyes to open them up, careful not to draw the line too close to the center, which makes the eyes look closer together.

Brushed multiple coats of mascara on my lashes. I owned three different colorsâVery Black, Black, and Brownish Blackâplus their waterproof versions.

Even as my hands weakened, I applied makeup. When my fingers curled, I twisted open bottles with my teeth. My magic tubes had chew marks on their sides.

Finally, I gave up closing thingsâtoo hard to reopen. I drove around with an open tube of Raisin Rage poised for application, propped in the center console of my car. That worked until the heat came. Then I had a molten plum mess.

My hand began to shake so much I could no longer line my eyes. The mascara wand quivered, so I ended up with more Brownish Black on my eyelid than on my eyelashes.

Failure was not an option. Me without makeup was NOT an option.

Vanity, thy name is Susan.

And I am claiming you. Caring about how you look is not shallow. Pride is the engine of self-respect. Nothing important ever was accomplished by letting the little things slip.

Besides, without makeup, I looked like I had not slept in a decade.

And John putting it on me? Never even entered the realm of possibility.

So I gave myself a late Christmas present: permanent makeup. A euphemism for: tattoo your face. Yes, that is how vain I am. I didn't think twice about needling ink into my eye sockets and lips.

I Googled away. A site advertising “wake up with makeup” caught my beady eye. The artist, Lisa, was a certified micropigmentation specialist. Yes, it's real. Lisa worked in a plastic surgeon's office, where they might tattoo an areola on a new breast after a mastectomy or eyebrows on an accident victim's face.

And she had worked on disabled people like me.

I called. Lisa said something right away that gave me confidence: “I refuse to tattoo anything unusual or that will look bad.” Women often asked her to tattoo mole beauty marks on their faces. She declines, she said, because they fade and look blotchy.

Lisa offered tattooing of the eyebrows, eyes, and lips. I signed up for all three.

“Oh, gosh, honey, are you sure?” Steph, also a makeup maven, said. “It's permanent. And painful.”

“And my only option,” I said.

Pain was not an issue for me. I have a high tolerance for pain. Pregnant in high heels, that was me. I have subjected myself to the most painful body maintenance women can elect to do: the Brazilian bikini wax. After that hair-ripping horror show, pain was not a problem.

“Well, I am definitely going with you,” Steph said. “To make sure her tools are clean and she doesn't turn you into a clown.”

It takes hours to tattoo a face. Brows, for example, are drawn one hair at a time, underneath a high-power magnifying glass. Lips take hundreds of pinpricks, each injecting a dot of color under the skin.

But oh, what color? That was the hardest part.

Lisa had custom-ordered a color she thought would work on my lips. She put some on me. It looked like orange Vaseline.

“You won't see that much orange,” Lisa said. Permanent ink, she assured me, looks vastly different under the skin.

“No way,” I said. “No orange!”

She tried a red. Now, I love red, but only at night.

I asked her to re-create Raisin Rage. She mixed up a plum, which I liked. We selected browns for the eyeliner and brows.

Lisa plucked my brows, then drew on the shape I wanted to add.

Heaven! I thought happily. I'll finally have arches! All my life, I had had skewer-straight brows.

Lisa numbed the area with a cream. She turned on the needle tool.

Zzzz . . . zzzz . . . zzzz

, it sounded each time it injected color.

I held my breath for the first ten minutes. Steph watched each stroke. The brown brow color looked purple. Steph asked if that was normal.

“Yes,” Lisa said. “Don't worry.”

She

zzz, zzz, zzz

ed for an hour on each brow.

She held a mirror up for me to see. My brows looked swollen and bloody, but otherwise fine.

Next came the eyes, open as she

zzz

ed a line flush with my lashes.

“I'd need a sedative for that,” Steph said.

I could not flinch. I could not move a hair with the needle so near my eye. I lay still as stone, a deep calm coming over me.

Get your Zen on, Susan.

We decided to add a wee flourish on the outside corners, like an extra-thick lash at the end. A makeup trick that makes eyes look larger and more open.

Lips were last. Lisa warned they would be the most painful and slathered numbing cream all over.

I wanted the entire lip colored, not just lined. Lipstick that has worn away, revealing just lipliner, has always looked ridiculous to me.

Lisa started

zzz-zzz-zzz

ing. I flinched. Lips are sensitive. Why else is a kiss so enchanting?

The wee dip in the center of the top lip is called a Cupid's bow. It felt like Cupid's bow was stabbing me as Lisa worked. I wanted to jump out of my sensitive skin.

I took a deep breath and thought of the most perfect kiss I ever had: a first kiss of intense ardor, yet not too hard, on lips just the right size, touching every millimeter of mine, the soft point of his tongue tracing the outline of my mouth.

I thought and thought of that kiss, that night so many years ago.

And then my lips were done.

I looked in the mirror. Swollen and bloody.

“The appearance will change in the coming weeks,” Lisa emphasized for the twentieth time. “The true color comes only after the skin has shed.”

She gave me an information sheet on what, when, where, including phases where the tattoos appear blue as skin sheds, or colors disappear altogether, or brows appear markedly larger and darker as they cure.

“Don't worry. It's going to be beautiful!” she said.

Steph and I got in the car for the drive home. I took a look in the rearview mirror. Groucho Marx stared back at me. My brows were big black slugs stuck on my forehead.

I did not look again, just hoped for the best. What's done is done, I thought. No sense in worrying.

Over the next few weeks, my face went psychedelic. I held my breath and religiously put on the healing ointment Lisa recommended and waited, checking off phases on my info sheet.

“How's it look?” I asked John, my husband of twenty years.

Poor guy.

I not only looked like Groucho Marx, I was also a Groucho. What in heaven's name was my husband of twenty years supposed to say?

“Let me put that ointment on so it heals faster,” he said.

Good answer.

As my body withered and my looks changed, John always had a good answer. He stuck with me without a word, even when my face was blotchy.

And then the makeup cured. It looked good. Far better than no makeup at all.

It was me, the way I had presented myself to the world for twenty years. Thinner in the cheeks. Less muscle control. But me.

Ah, makeup. Still mine to control.

A part of my body that will remain the same, permanently.

I

met John Wendel at Lake Lytal Pool in suburban West Palm Beach. I was a lifeguard, just graduated from UNC. John was a high school teacher, swim coach, and former collegiate swimmer who practiced there.

I was transfixed watching him swim, his long, fluid strokes torpedoing his gorgeous bodyâhe was a six-foot-one bronze statueâthrough the water.

John was so handsome that after two years of razzin' each other, I had a friend call and tell him he'd been selected for the Palm Beach Lifeguard Swimsuit Calendar.

John called me that night, the sap. I was in graduate school by then, and we were dating long-distance. “Hey, Susan, guess what?” he said. “I'm going to be in a swimsuit calendar. They let me pick the month. I asked for December because of your birthday.”

“John . . .”

“Yes?”

“What day is it today?”

“Tuesday.”

“No, what date?”

“April first . . .”

April Fools' Day. He laughed.

The April Fools' Day calendar-hunk caper started a tradition that continued all the way through Marina and Aubrey's chocolate-radish/slippery toilet classic. In twenty-three years, we have pulled some zingers, especially in the early days.

One year, I hid John's pricey bike, making him think it had been stolen.

“Goddammit!” he hollered as he hurtled his bike helmet across the apartment in frustration.

“April Fools!” I said.

The next year, oh boy, he got me back good. We were fooling aroundâI mean a moaner of a roll in the darknessâand John called out a name. “Beth! Beth!”

His old girlfriend.

'Twas I who went hurtling across the room that time.

I've always enjoyed that about John: he can laugh at himself. And he can laugh at me. Inside that beautiful body, I recognized a soul: a modest (yes, really), smart, steady-yet-fun soul.

When John talks about meeting me, though, he mentions my shorts. “She was wearing a University of North Carolina sweatshirt, and these blue shorts.” He always stops there and shakes his head, thinking about my rear end.

I trust John with my life, and now with the lives of our children. In more than twenty years together, I have never seen him make a rash, senseless decision. (Except once, purchasing a used Ford with 80,000 miles on it.)

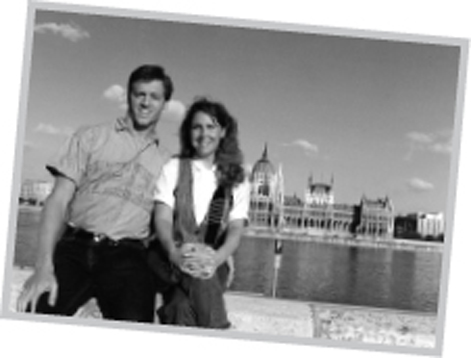

Even marriage was a practical decision. John received a Fulbright Commission berth to teach at a high school in Budapest, Hungary, in 1992. I had urged him to apply. Actually, I filled out the Fulbright application for him. He's an awful procrastinator.

John asked if I would go with him. We had to be married for me to accompany him on Fulbright functions, so one of us said, “Why don't we get hitched?”

We don't remember who.

And the other said, “Okay.”

We casually mentioned it to my mother at Thanksgiving. Within days, she had the church, the pastor, the music, the organist. It was so swift, people musta wondered if I was pregnant. Let 'em wonder! I thought.

All I had to do was buy a wedding dress and show up. Which I did. Smiling the whole time. It was a small wedding, just family and our closest friends, at a nondenominational church.

Nancy, of course, was there.

We spent our wedding night at the local Hilton. Sat back in bed, looked at each other, and said, “What the hell did we just do?”

Five months later, we were living in Budapest.

People who know me a little think that doesn't sound like me at all. I'm a very together person. I don't make rash decisions.

When they know me better, they say, “That's so Susan.” When I know what I want, I grab it. No waiting. No what-ifs. Just stop talking and do it already.

I wanted John, and I wanted Budapest. I was twenty-five. I was an international studies major with a master's degree in my cherry-picked portable profession, journalism.

It was time for travel and adventure.

Budapest turned out to be one of the best decisions of our lives.

It was 1992, so the Berlin Wall had just come down. The city was rejoicing. Businesses going up. Statues coming down. It was the Wild West. Anything possible. A magnet for hucksters, youngsters, dead-enders, dreamers, anyone who wanted a chance.

And writers. I must have met a hundred. I met a recent Princeton graduate who was starting an English-language newspaper, the

Budapest

Post

. Within a week, I was writing articles. Within two months, I was a senior editor, mentoring recent college journalism grads out to see the world.

At a news conference, I asked a question of Queen Elizabeth. At another, Boris Yeltsin. I flew on a relief mission over Bosnia and covered the Bulgarian rose harvest.

When I sat in the Hungarian Parliament, I'd see legislators with our paper, reading my articles. I was a twenty-five-year-old who didn't speak Hungarian, who had a translator for most of her interviews, and I was helping shape the opinions of legislators!

Then the kid ran out of money. The paper went belly-up. But someone knew someone at

Forbes

, the magazine of the ultra-wealthy. The paper was reborn as the

Budapest Sun

. My salary was now a pile of Hungarian cash. No checks or bank accounts. John and I hid the wad in a book in our apartment.

When we had money, we scoured the city, toured the nation and neighboring ones (we were almost killed in traffic in Turkey!), attended operas and concerts. We drank homemade wine in the midafternoon Budapest winter gloom.

When our cash ran out, we sat tight until the next payday. Laughing, talking, exploring each other. Surviving, like the newspaper, hand-to-mouth and day-to-day.

Those days, those adventures together, bonded us. Like glue on a piece of furniture, they were the invisible underpinning that held us together for a lifetime, strained or unstrained.

T

he Fulbright ended. We came home, after two years abroad, to boring jobs and American excess. John didn't like his teaching position. I didn't like being a grunt at the

Palm Beach Post

after two years as a managing editor in Budapest. Even our small apartment with the air conditioner unit stuck in the dining-room window felt hollow.

And quick as a Florida thunderstorm, depression was upon me.

Thwack! Boom!

I did not realize I was mentally ill until I'd lost fifteen pounds. Until my mind was so frazzled by lack of sleep, I'd have a panic attack when I lay down to try again.

In Hungary, every sense had been massaged with new sights, sounds, tastes, smells. Even the ordinary journalism assignments were fascinating.

Like when I was dispatched to cover the Eastern European debut of the Chippendales, an America-based franchise of muscular men who stripped down to thong undies and thrusted for the hundreds of young women assembled.

“DO YA WANNA GET NASTY?” the buff boys hollered to the audience.

Which responded with absolute silence.

Delight.

Now I felt lousy, and everything seemed blah. John, increasingly depressed himself, felt powerless. We argued. I stayed with my sister for a brief spell. Stephanie drove me straight to the psychiatrist.

“Is the television talking to you?” the psychiatrist asked.

“I'm depressed, not psychotic!” I replied. The doc put me on an antidepressant. I felt much, much better.

I deeply believe we are the masters of our minds. That healthy, we can choose how we feel. But we are also our minds' lone caretakers, and we must keep them healthy. Now I practice my slow breathing, getting my Zen on. Living with joy.

Back then, John and I sought another post abroad, trying to recapture the wonder.

About a year later, we went to an international job fair for teachers. “There's a teaching position at a high school in Colombia,” John pointed out. “They don't have spouse benefits . . . but they do have a job running the school yearbook.”

My heart skipped. It was 1995, and Colombia was in the middle of a drug war. The year before, a soccer player on the national team had accidentally kicked the ball into his own goal during the World Cup. When he returned home, he was murdered. At that time, Colombia was widely considered the kidnapping capital of the world.

I agreed anyway. Life's an adventure, right? We signed a two-year contract.

This adventure wasn't so carefree. The cocaine wars were in their dying stages, but violence was rampant. Every corner shop had an armed guard. I'm talking ice cream shops, not banks. The school where John and I taught had a metal gate and armed guard turrets. There were men milling outside the gates with Italian suits, bad dental work, and machine guns. They were the students' bodyguards.

Kidnapping had devolved to a street-level crime: people were getting snatched on their way to the grocery store.

“I want to go home,” I told John after seven months.

Honorable John didn't want to break our two-year contract. But I finally convinced him. We would leave at the end of the school year.

A month later, we hiked into the mountains during spring break. We were headed to La Ciudad Perdida (the Lost City), site of an ancient civilization hidden in the jungle for hundreds of years. It had only been rediscovered in the 1970s.

The hike was majestic. Mountains. Canopied forest. Streams. Toucans flying across terraced landings.

It was also long days of walking uphill. With a guide and armed bodyguards, because this was guerrilla country. No showers. No toilets. Our group slept in hammocks on the second story of open-sided huts. On the first story, a fire was kept lit to ward off the bugs. The smoke kept me awake.

By the sixth day, I couldn't take it anymore. It was raining. I was sick. I snapped. “That's it,” I said, on the verge of tears. “I'm tired. I'm hungry. I'm filthy and nauseous and sore. And I think I'm pregnant!”

I turned to stomp off into the jungle and slammed right into a support post for the hut. I fell flat on my back in the mud.

Splat

.

And that's how John found out about our first child. Then did the mathâback to our celebration on the night we'd decided to go home.

Life is perfect like that. Otherwise I would have delayed and delayed having children, wanting to travel more. I was thirty years old.

The pregnancy began as twins and was high-risk. We couldn't afford health insurance without our jobs, so we had to stay in Colombia for another year. Talk about nerve-rackingâtry being pregnant at an altitude of 9,000 feet in the kidnapping capital of the world.

I miscarried one twin.

Then, a week short of due, the remaining baby stopped moving. I was at school, working, so I talked to the nurse.

“Eat sugar,” she said.

It didn't work. The baby didn't start moving again. By the afternoon, we were in panic mode. John ran out into the rain to hail a cab to the hospital, couldn't find one, and stopped the next best thing.

“Come on,” he said, dripping wet. “I got us a ride.”

It was the kindergarten school bus. Full of children. Sure enough, it went right past the hospital, opened its hydraulic doors with a sigh, and dropped us off.

“What have you had to eat in the last six hours?” the anesthesiologist asked.

I had taken the nurse's sugar advice. “Two Cokes and three brownies,” I replied.

The doc gave me that look. You know the one. Pathetic.

An hour later, I was in the operating room. The baby was breech, and the cord was wrapped around its neck. It would have to be a C-section. John watched them make the incision. Then his face turned gray and he started to sway.

“Unlock your knees!” I yelled. “Don't pass out!”

He did and stayed upright. I heard a cry and asked him the baby's sex.

“I think it's a girl.”

“What do you mean, âyou think?'Â ”

“Well, everything's kinda swollen.”

We could not name our child without meeting her. So a few hours later, in a hospital bed, I asked John what name popped into his head when he saw our little girl.

“Brie,” he said.

Like all babies, she had been covered with white goo.

I rolled my eyes and decided on Ella.

The notary said the name would not be approved. In Spanish,

ella

means “she.” Nope, it wouldn't do. The woman didn't care if it was common in English.

So we gazed at our baby for days. At the wonder of her. Finally, we named her Marina.

Partly because it sounded Spanish. Partly because it was Greek, like my mother. Mostly because she had blue eyes. A calm, gentle blue that reminded me of the ocean on a sunny day, a place I always felt safe and warm.

Oh, Marina. Beautiful girl. I remember holding you. And learning to nurse you.

My milk came in full force the night we arrived home from the hospital. “You look like an exotic dancer,” John said of my supersized self. This was the same man who had brought my thong underwear and skinny jeans to the hospital, as if I was going to immediately spring back into my old shape.