Upon the Altar of the Nation (57 page)

Read Upon the Altar of the Nation Online

Authors: Harry S. Stout

But in 1864, Frémont attracted little support. Frémont’s strongest supporter, the radical anti-Lincoln abolitionist Wendell Phillips, represented an alliance sure to win more enemies than friends. Few Republicans or Democrats expressed much interest. At the nominating convention on May 31 in Cleveland, the “Radical Democratic Party” denounced Lincoln’s softness on abolition and reconstruction. They further advocated that Congress, not the executive, set plans for reconstruction that included the confiscation of rebel land for redistribution. But they garnered little national support.

13

13

For Martha LeBaron Goddard, an admirer of Wendell Phillips, the prospects did not look good: “I was dreadfully disappointed in the Cleveland convention, for I had hopes that the opposition to Lincoln might accomplish something. Now I despair—Fremont is my man, but his party looks forlornly weak to me, so far as I know anything about it; and I suppose we and the poor negroes must suffer another 4 years of Abe’s slowness and feel guilty and mean explaining and apologising for every decent thing he has done.”

14

If Lincoln failed to impress Goddard, the generals were a different story: “This last month of fighting has told upon the Worcester soldiers, and some of our best and bravest soldiers have fallen.... Grant and Lee are by far the most interesting men in the country to me now.”

15

14

If Lincoln failed to impress Goddard, the generals were a different story: “This last month of fighting has told upon the Worcester soldiers, and some of our best and bravest soldiers have fallen.... Grant and Lee are by far the most interesting men in the country to me now.”

15

Abijah Marvin, an abolitionist minister, also evidenced concern over a war fought for war’s sake. Citing earlier American barbarities in the Seminole War and Mexican War, he wondered if the present war was any different: “When I picture to myself two armies composed of such profane men rushing into deadly conflict, the idea of humanity seems to be withdrawn, and to my mind’s eye, two armies of incarnate fiends are venting the rage of hell itself. O what a terrible necessity is war!”

16

16

In the Confederacy President Davis continued to do battle with the Carolinas and Georgia over his policy of centralization and conscription, but the army seemed in good spirits.

17

Longstreet’s corps returned to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, ready to help “Marse Lee” beat off a Union attack. And General P. G. T. Beauregard was reassigned from Charleston to lead the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, with responsibility for defending Richmond and North Carolina against Butler’s threatened invasion from the South. While no large battles had taken place since the fall of 1863, the pieces were falling neatly into place for destruction of military and civilian lives and property on an unprecedented scale. A shaken writer for the Richmond Daily Whig recognized that “upon the eve of a momentous campaign, within the period of which lie undisclosed events, inscrutable to the most earnest gaze, affecting the destiny—the very existence perhaps—of our people as a free people.”

18

17

Longstreet’s corps returned to Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, ready to help “Marse Lee” beat off a Union attack. And General P. G. T. Beauregard was reassigned from Charleston to lead the Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, with responsibility for defending Richmond and North Carolina against Butler’s threatened invasion from the South. While no large battles had taken place since the fall of 1863, the pieces were falling neatly into place for destruction of military and civilian lives and property on an unprecedented scale. A shaken writer for the Richmond Daily Whig recognized that “upon the eve of a momentous campaign, within the period of which lie undisclosed events, inscrutable to the most earnest gaze, affecting the destiny—the very existence perhaps—of our people as a free people.”

18

In his classic treatise

On

War, Carl von Clausewitz defined war as “politics by other means,” and so it had begun with the Civil War. But by 1864, as battles resumed, war was becoming its own end. Richmond’s papers could print little else than news of the war—and with it stories of the generals who dueled like industrial knights commanding engines and explosives alongside horses and sabers. Headlines fed the public lust for new conquests. Civilian anticipation for massive battles would not wait long to be satisfied. If Antietam stands as the military and political “crossroads” of the war, 1864 would stand as the moral crossroads of a war pursued with unprecedented violence on soldier and civilian alike. By 1864 even Lincoln was through with efforts at compromise and conciliation. With black soldiers under arms, there would be no further talk from Lincoln of colonization or compensated emancipation. Instead, it was all-out war.

On

War, Carl von Clausewitz defined war as “politics by other means,” and so it had begun with the Civil War. But by 1864, as battles resumed, war was becoming its own end. Richmond’s papers could print little else than news of the war—and with it stories of the generals who dueled like industrial knights commanding engines and explosives alongside horses and sabers. Headlines fed the public lust for new conquests. Civilian anticipation for massive battles would not wait long to be satisfied. If Antietam stands as the military and political “crossroads” of the war, 1864 would stand as the moral crossroads of a war pursued with unprecedented violence on soldier and civilian alike. By 1864 even Lincoln was through with efforts at compromise and conciliation. With black soldiers under arms, there would be no further talk from Lincoln of colonization or compensated emancipation. Instead, it was all-out war.

CHAPTER 34

“IF IT TAKES ALL SUMMER”

S

hortly after midnight on May 4, 1864, Grant began the dreaded spring campaign by posting the Army of the Potomac across the Rapidan under cover of darkness. On the other side, Lee waited patiently in his command headquarters at Orange Court House with his veteran army of just under sixty-five thousand loyal disciples willing to sacrifice themselves for their master. Instead of challenging Grant’s invasion at the Rapidan, Lee posted his army north of Richmond in the thick and familiar tangle of trees and undergrowth that was the Wilderness.

hortly after midnight on May 4, 1864, Grant began the dreaded spring campaign by posting the Army of the Potomac across the Rapidan under cover of darkness. On the other side, Lee waited patiently in his command headquarters at Orange Court House with his veteran army of just under sixty-five thousand loyal disciples willing to sacrifice themselves for their master. Instead of challenging Grant’s invasion at the Rapidan, Lee posted his army north of Richmond in the thick and familiar tangle of trees and undergrowth that was the Wilderness.

The choice was brilliant. Rather than confront Grant’s superior numbers in a frontal assault, Lee would force Grant to come to him on his turf, just as he had done with Hooker at Chancellorsville, five miles to the north. In the Wilderness, there would be no massed army to flank—or even to see. Artillery, which had proved so devastating at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, would be of little use. Lee hoped that by effectively silencing Federal artillery and capitalizing on the advantages of terrain and local knowledge, he might once again humble the Goliath from the North.

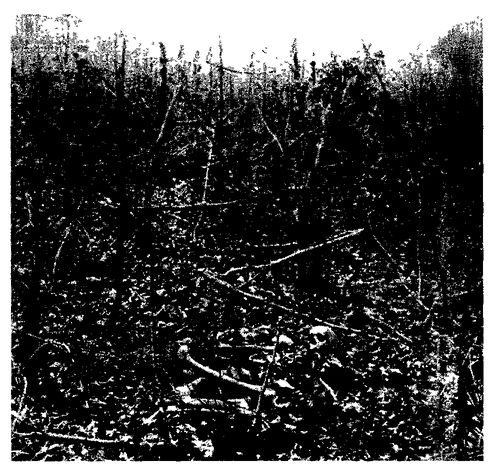

Winslow Homer’s painting of the Wilderness captured the haunting, almost surreal quality of the terrain where the two armies would soon grapple in a desperate battle. The dark forestation was so thick with small pines and scrub oak, cedar, and dogwood that visibility all but ended beyond ten yards, making coordination between large military elements virtually impossible.

Though fighting without Stonewall Jackson and unhappy with Longstreet’s tardiness at Gettysburg, Lee still enjoyed a general corps roughly the equal of Grant’s in terms of ability and experience. Such were the talents of the battle-hardened commanders on both sides that none would flinch or run. Neither would the equally hardened soldiers, Darwinian survivors all. Great commanders and veteran soldiers ensured great battles—and great losses.

“Bones of Dead Soldiers in the Wilderness.” This photograph of skeletons in the woods captured the tangled morass of the Wilderness, where some of the war’s fiercest fighting took place.

Grant thought he knew all about the terrain from reports about the debacle at Chancellorsville. Hoping to get through the Wilderness as quickly as possible, he divided his forces into two columns marching in two directions. But his hopes were not realized.

1

1

Like Gettysburg, the Battle of the Wilderness began accidentally with a chance early-morning encounter on May 5 between Gouverneur K. Warren’s Fifth Corps and Richard Ewell’s Second Corps on the Orange Turnpike. Warren was ordered to attack what he believed to be no more than a division. When it became apparent that Ewell’s entire corps was on the road before him, Warren realized that this attack would soon rise to the dignity of a full-fledged battle. Fierce fighting broke out on Orange Plank Road between Confederate A. P. Hill’s advancing Third Corps and Winfield Scott Hancock’s Second Corps. Though outnumbered forty thousand to fifteen thousand, Hill fought a brilliant and successful holding action by shifting his interior lines to concentrate his limited forces against the specific points of Federal attack.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Hill was so exhausted and weakened from the day’s fighting that he failed to adequately reorganize his front, which remained scattered and unprepared for renewed fighting the next morning. At the same time, Lee worried about Ewell’s health and resolution in the face of battle. Lee could ill afford to lose any of his depleted warrior priests. Fortunately, he still had Longstreet, who was moving rapidly to join up with him.

By morning Longstreet had still not arrived, leaving Lee shorthanded and desperate. But timing is everything in battles, and just as hope was waning, Lee spotted approaching soldiers. He asked where they were coming from. When the answer came back “Texas,” he knew that Longstreet had arrived.

With uncharacteristic glee, Lee left his position and rode to meet the loyal Texans. For their part, they were no less moved by the sight of “Marse Robert” in the field. One courier cried out, “I would charge hell itself for that old man.” Caught up in a frenzy of his own, Lee assumed a position as if to lead the charge until cries of “Go back!” “Lee to the rear!” rang through Longstreet’s corps. When, at length, Lee’s staff officer caught the bridle of Lee’s mount Old Traveller and turned Lee back, the rebels followed Longstreet with renewed passion into the fray.

The moment was indeed Longstreet’s, and he never shone brighter. The energized rebels pushed Hancock’s Yankees hard down the Orange Plank Road and single-handedly turned the tide of attack. With room to breathe, Hill’s units reordered and reconnected with Ewell as the new center of the Confederate line.

2

Later, Longstreet praised the intrepid courage of his men “at the extreme tension of skill and valor.”

2

Later, Longstreet praised the intrepid courage of his men “at the extreme tension of skill and valor.”

As Longstreet pushed forward down the Orange Plank Road, the Federals fell back, leaving Lee’s forces in place to turn Grant’s left flank at Brock Road and roll up his army. But just as rapidly the tide turned again. At the critical moment of attack, Longstreet was struck by a volley of fire issued by his own pickets and fell, badly wounded in his neck, coughing blood and unable to continue. The “Old War Horse” had fallen at the hands of his own men, just as Jackson had fallen in the Wilderness a year before.

Longstreet would live to fight another day, but his glorious moment was lost. Still, this would not be Lee’s last thwarted opportunity. At the other end of Lee’s line, General John B. Gordon’s scouts informed him that, incredibly, Union General John Sedgwick’s right flank was exposed and “in the air.” A skeptical Gordon crawled past his lines toward the end of Grant’s breastworks, where he beheld the most amazing sight: “There was no line guarding this flank. As far as my eye could reach, the Union soldiers were seated on the margin of the rifle pits, taking their breakfasts.”

3

3

Ecstatic at the sight, Gordon proposed that he attack at once. His immediate superior, timid Jubal Early, refused permission to make the assault. When apprised of Gordon’s intelligence hours later, Lee immediately countermanded Early’s orders and sent Gordon forward in the waning daylight. The surprise was total as wave after wave of Gordon’s rebels rolled back entire regiments of stunned Yankees.

Throughout the day, men fought in clumps of desperate engagement that became lonely worlds unto themselves. Lacking any visibility or contact, soldiers sometimes fired on their own men. Worse, in the dense and dry underbrush, artillery and musketry ignited fires up and down the line. Dead trees burned like kindling as two hundred wounded Union and Confederate soldiers and their fallen horses suffocated or burned where they lay. Victory could not be seized; precious daylight waned and rebel soldiers got caught in crossfire from their own troops. As later summarized by a recovered Longstreet: “Thus the battle, lost and won three times during the day, wore itself out.”

4

4

Grant knew he had not taken the day, but was consoled by the fact that Longstreet was removed. His loss, Grant observed, “was a severe one to Lee, and compensated in a great measure for the mishap, or misapprehensions, which had fallen to our lot during the day.”

5

Grant determined nevertheless that Lee’s entrenched defenses were too powerful to carry. The next morning, May 7, both armies remained in their respective positions along the five-mile line from Germanna Plank Road to Spotsylvania Court House. With Lee well entrenched in the Wilderness, any offensive would have to originate with Grant. He was not yet ready to roll the dice again, and with good reason. The losses from the Wilderness fight were staggering on both sides. Of 115,000 Federals engaged, 17,666 were killed, wounded, or missing; of Lee’s 65,000 Confederates, the combined casualties stood at more than 7,500. Furthermore, Lee had lost the services of two of his three commanders. In addition to Longstreet, A. P. Hill was too ill to continue in front of his army and had to be replaced by Jubal Early.

5

Grant determined nevertheless that Lee’s entrenched defenses were too powerful to carry. The next morning, May 7, both armies remained in their respective positions along the five-mile line from Germanna Plank Road to Spotsylvania Court House. With Lee well entrenched in the Wilderness, any offensive would have to originate with Grant. He was not yet ready to roll the dice again, and with good reason. The losses from the Wilderness fight were staggering on both sides. Of 115,000 Federals engaged, 17,666 were killed, wounded, or missing; of Lee’s 65,000 Confederates, the combined casualties stood at more than 7,500. Furthermore, Lee had lost the services of two of his three commanders. In addition to Longstreet, A. P. Hill was too ill to continue in front of his army and had to be replaced by Jubal Early.

Amazingly, despite the losses on both sides, neither commanding general was deterred. As Grant smoked a cigar and whittled wood, preoccupied with his next move, Lee correctly ascertained that Grant was neither a retreating McClellan nor a rash Hooker, but rather a general of grim determination. As Grant’s army slid past Lee’s army and moved south, Lee also deduced that his destination was Spotsylvania Court House, a small village where a number of roads converged with vital strategic implications for command and communications.

For the first time, Lee faced a general who would press on the offensive no matter what the cost in human sacrifice. No moralists moved to caution Grant. To the contrary, the people cried for more. Grant’s strategy left no room for nuance. “It was my plan, then, as it was on all other occasions,” he would later write, “to take the initiative whenever the enemy could be drawn from his intrenchments if we were not intrenched ourselves.”

6

At that moment in the Wilderness, with Grant’s decision to press on, the fate of the Army of Northern Virginia was sealed. But not even Grant could estimate the butcher’s bill that Lee would extract.

6

At that moment in the Wilderness, with Grant’s decision to press on, the fate of the Army of Northern Virginia was sealed. But not even Grant could estimate the butcher’s bill that Lee would extract.

Other books

Scandal Never Sleeps by Shayla Black, Lexi Blake

Blind Faith by Cj Lyons

Just One Spark by Jenna Bayley-Burke

Immortal Essence Box Set: Aligned, Exiled, Beguiled by Rashelle Workman

The Civil War: A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian by Shelby Foote

Dancing Shoes and Honky-Tonk Blues by MCLANE, LUANN

Murder on the Ol' Bunions (A LaTisha Barnhart Mystery) by Moore, S. Dionne

Fallen Angel by Melody John

Heat Vol. 4 (Heat: Master Chefs #4) by Kailin Gow

Dangerous by Reid, Caitlin