Upon the Altar of the Nation (77 page)

Read Upon the Altar of the Nation Online

Authors: Harry S. Stout

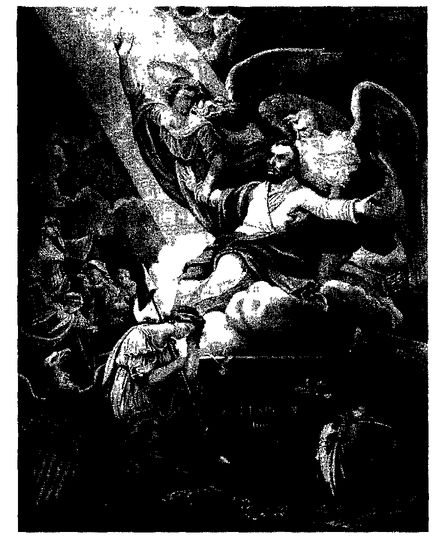

Apotheosis

by D. T. Wiest, modeled after John James Barralet’s

Apotheosis of George Washington.

Ascending to immortality, Abraham Lincoln is pictured surrounded by angels. At his feet are Columbia—the reunited nation—and a Native American, with heads bowed.

by D. T. Wiest, modeled after John James Barralet’s

Apotheosis of George Washington.

Ascending to immortality, Abraham Lincoln is pictured surrounded by angels. At his feet are Columbia—the reunited nation—and a Native American, with heads bowed.

The Universalist pastor Adoniram J. Patterson, who held the opposite opinion of evangelicals on almost all issues save the nation, agreed with Boardman:

The haters of liberty crucified the son of Mary. But he rose to life again, and his resurrection is celebrated by the Christian church throughout the world. By his death he acquired a power and influence which he could never have attained in life. So shall it be with our lamented dead [President]. Power shall be born of his ashes, even as a corn of wheat dying brings forth an hundred fold,—and the wrath of man be made to praise thee, O God.

8

8

Abraham Lincoln, the single most photographed subject during the Civil War, could not escape the photographers’ selective display of images. With his assassination and apotheosis into America’s messiah, photographers, statesmen, and family refused to reproduce the most recent photographs of the living Lincoln, taken in 1865 by Alexander Gardner and Henry Warren. The reason? He looked too thin and emaciated:

Most portraitists resolutely refused to record the physical consequences of the Lincoln presidency on its chief executive, for as a martyr, they probably reasoned, he should not appear wasted or even haggard. Part of the dying-god legend required that its heroes be struck down in their prime. So printmakers romanticized Lincoln’s features in their post-assassination portrayals, making his now-gaunt physique heroic rather than taking the commercial risk required to reveal the truth.

9

9

As word spread throughout the South of the assassination, no celebrations ensued. Real enemies celebrate enemy deaths at the hands of insurgents as a call for guerrilla warfare. But in this war, they remained Americans all. Richmond’s Sallie Putnam, writing from her occupied city, conceded, “In the wonderful charity which buries all quarrels in the grave, Mr. Lincoln, dead, was no longer regarded in the character of an enemy.”

10

10

On April 17 General Sherman met with a shocked General Johnston at the James Bennett house near Durham Station, North Carolina. Johnston feared the assassination would ruin negotiations for a generous peace and informed Sherman that it was a great “calamity” for the South no less than the North. The two then began negotiating not only the surrender of Johnston’s army but the surrender of all armies in the field. Neither president was consulted on these conversations, and even Grant remained in the dark. From these negotiations emerged a remarkably merciful “Memorandum on basis of agreements,” drawn up by Sherman, that called for an armistice by all armies in the field. Beyond that, the memorandum dictated terms of reconstruction, agreeing to obey Federal authority, and reestablish the Federal courts. The existing state governments would be recognized when their officials took oaths of allegiance to the United States. In return, the United States would guarantee rights of person and property and issue a general amnesty for Confederates.

11

In that memorandum, General William Tecumseh Sherman, the “scourge of the South,” stood incongruously as the Confederacy’s last best hope. No one would be more hated in Southern memory than Sherman, but no American showed more generosity of spirit at that moment than Sherman.

11

In that memorandum, General William Tecumseh Sherman, the “scourge of the South,” stood incongruously as the Confederacy’s last best hope. No one would be more hated in Southern memory than Sherman, but no American showed more generosity of spirit at that moment than Sherman.

Sherman clearly went well beyond anything Grant had negotiated at Appomattox, though he always maintained that everything he did was in the spirit of Lincoln’s wishes as they were expressed on the River Queen. But clearly he had overstepped his bounds and usurped powers that were not his to exercise. An outraged Congress and cabinet immediately assailed the memorandum, and Grant was promptly dispatched to meet with Sherman and rein him in. On April 24, the two generals and friends met, and Grant gently reminded Sherman that he did not have the authority to impose terms of surrender and reconstruction. President Johnson, Sherman was informed, had rejected the memorandum. Sherman was to apprise General Johnston of the rejection and allow two days for unconditional surrender without terms, after which hostilities would resume.

Throughout the North, an outraged and still mourning nation learned of Sherman’s agreement, and Northern newspapers assailed the terms, crying instead for revenge. For his part, Sherman was equally outraged. He fumed against Secretary of War Stanton and the New York papers for printing a communique of March 3 from Lincoln to Grant stating that the generals should accept nothing but surrender and should not negotiate peace. Sherman claimed he had never received such a message and reiterated what Lincoln twice told him aboard the

River Queen

on March 27 and 28:

River Queen

on March 27 and 28:

[I]n his mind he was all ready for the civil reorganization of affairs at the South as soon as the war was over; and he distinctly authorized me to assure Governor Vance and the people of North Carolina that, as soon as the rebel armies laid down their arms, and resumed their civil pursuits, they would at once be guaranteed all their rights as citizens of a common country; and that to avoid anarchy the State governments then in existence, with their civil functionaries, would be recognized by him as the government de facto until Congress could provide others.

12

12

Some people looked for plots and conspiracies. Certain that the South was behind the assassination, Northern papers railed against Sherman, complaining that “the favorable terms given to the rebel generalissimo in surrendering” encouraged bold moves. In the view of such critics, however, Southern conspirators had only managed to remove the South’s best hope. Ultimately, one religious writer declared, God allowed this to happen “in a way utterly unexpected and afflictive [so that] he has opened the eyes of the blind to the malignant and implacable character of the rebellion. He has removed the one most disposed to a policy of leniency.”

13

Now was the time for revenge!

13

Now was the time for revenge!

In like fashion, the

New York Observer

spread the rumor of Confederate machinations: “As yet there is no reason to believe that the leaders of the Rebellion had any part or lot in the crime; but the crime itself is nothing more and nothing less than the personification of the whole insurrection.... This department has information that the President’s murder was organized in Canada, and approved in Richmond.”

14

New York Observer

spread the rumor of Confederate machinations: “As yet there is no reason to believe that the leaders of the Rebellion had any part or lot in the crime; but the crime itself is nothing more and nothing less than the personification of the whole insurrection.... This department has information that the President’s murder was organized in Canada, and approved in Richmond.”

14

On April 19 funeral services were held for President Lincoln. In thinking ahead to the ceremonies, Grant instructed his officers to send a black regiment to march in the procession with the Army of the Potomac. After a brief service, the funeral carriage carried the slain president past throngs of mourners to the rotunda of the Capitol.

Throughout the North and in “Union” pulpits in the South, the messianic praises of Lincoln rang like the peals of the mourning bells. Many lauded his Christlike character, averring that “malice seems to have had no place in his nature.” To complete the identification, Lincoln’s faith was also transformed into that of a converted evangelical. In a sermon preached in the Union Church of Memphis, Tennessee, T. E. Bliss began the mythmaking with the description of Lincoln as “[h]e who but a few months ago told the story of his love for Jesus, in tears, and with all the simplicity of a child.”

15

15

For Frederick Douglass, Lincoln’s assassination spurred apocalyptic sensibilities tied to the American nation and its new birth of freedom. As the news set in, Douglass sensed, “a hush fell upon the land as though each man in it heard a voice from heaven and paused to learn its meaning.” The meaning Douglass divined lodged in what his biographer, David Blight, terms a “millennial nationalism” in which

[t]he United States was seen as God’s redemptive instrument in history, and with providential appointments went burdens of world significance. The notion of an elected nation included both promise and threat. How could the model republic, called to nationality by the Founding Fathers, endure its own tragic flaws? The Civil War became the crucible in which the nature and existence of that nationalism would be either preserved and redefined, or lost forever.

16

16

Alongside his purported lack of malice, Lincoln’s morality received significant attention. Lincoln had, one eulogist claimed, given the nation a “moral genius.” Another amplified on the theme, noting, “It was mainly his adherence to ethical principles in political discussions that gave such point and force to his reasonings; for no politician of this generation has applied Christian ethics to questions of public policy with more of honesty, of consistency, or of downright earnestness.”

17

17

If Lincoln had a problem, most eulogists agreed, it was that very likeness to Christ, especially as it appeared in his lack of malice or revenge toward the South. Some went so far as to suggest that in God’s Providence, Lincoln had been taken up prematurely because he would not “have been equal” to the harsh penalties that divine justice required of the beaten South, but instead would “have been too lenient.”

18

18

In an unpublished sermon on Lincoln’s death, Abijah Marvin likened Lincoln to Jonathan Edwards and Stephen Douglas. Death spared all three greats from later failures. For Edwards, his magisterial History of Redemption project, if completed, “would never satisfy the majesty of the vision.” Douglas “was taken from the evil he might do if his life were prolonged.” And “clouds seemed to be gathering over [Lincoln’s] head” in regard to reconstruction. But from all of that, he had been saved: “Fortunate in his death he has entered the pantheon of history as the great and good president—Lincoln.”

19

19

Hard justice required a different president in peace than Lincoln would have been. Many Christian moralists in the North agreed that justice required revenge:

If now we strip all who have knowingly, freely, and persistently upheld this rebellion, of their property and their citizenship, they will become beggared and infamous outcasts ... like Cain, with the brand upon their foreheads, and with a punishment greater than they can bear.... The Union people of the South ... would plant farms and villages upon the old slave plantations; and with our help in schools and churches, a new social order would arise upon the basis of freedom and loyalty.

20

20

One of the more astute sermons to be preached about Lincoln’s assassination came from N. H. Chamberlain, who delivered it to his St. James parish in Birmingham, Connecticut. Chamberlain recognized that blood was needed for America’s religion to bloom. The Civil War, together with Lincoln’s assassination, provided what mere rhetoric could never achieve—a sacred compact. He began, as he must, with blood: “A nationality is a sublime, a solemn, a sacred thing. It has its history, its prophecy, its destiny. It is always built upon solemn sacrifices; it is a compact always sealed with blood.”

From blood he turned to the national totem for which the blood was shed: “Our flag ... is the symbol of our nationality, and is sacred with its history. As a nation changes or advances, so does its flag, which wraps in its folds its story.... The last four years have encircled it with a new halo of glory. It hath endured a new baptism, wherein the smoke of battle stained not and the fire consumed not.” From the flag in general, Chamberlain turned to its sacred component parts:

Henceforth that flag is the legend which we bequeath to future generations, of that severe and solemn struggle for the nation’s life.... Henceforth the red on it is deeper, for the crimson with which the blood of countless martyrs has colored it; the white on it is purer, for the pure sacrifice and self-surrender of those who went to their graves upbearing it; the blue on it is heavenlier, for the great constancy of those dead heroes, whose memory becomes henceforth as the immutable upper skies that canopy our land, gleaming with stars wherein we read their glory and our duty.

Other books

The Dress Lodger by Holman, Sheri

Magic Below Stairs by Caroline Stevermer

Here Be Dragons by Alan, Craig

CONCEPTION (The Others) by McCarty, Sarah

Winning Her Over by Alexa Rowan

Jezebel by Jacquelin Thomas

One Summer in Santa Fe by Molly Evans

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You: A Novel by Cameron, Peter

The Archon's Assassin by D. P. Prior