Urchin and the Heartstone (31 page)

Following Larch and Cedar, they ran. Little was said, apart from Lugg’s exclamations about the size and structure of the tunnels, and the Whitewings squirrels explaining that these weren’t really tunnels, they were burrows.

“Nice burrows, then,” said Lugg, then stopped.

“Quickly, Lugg,” ordered Cedar.

“Sh!” said Lugg, and flattened himself on the ground, his ear down and his face grim with concentration. He scrambled up and listened at the wall. Urchin and Juniper glanced over their shoulders and curled their claws in impatience.

“Stand still!” said Lugg with a frown, then got to his paws and continued running. “There’s moles running along those tunnels like there’s Gripthroat behind them,” he muttered. “Wish I knew what was going on.”

“Are they following us?” gasped Cedar.

“No,” said Lugg. “Heading east. Toward Mistmantle.”

Juniper was falling behind, his breathing coming in rasps and wheezes. Urchin reached for his paw and pulled him along as he ran.

“King Silverbirch sent the moles,” gasped Urchin, still running. “He wants Mistmantle.”

“Well, he ain’t getting it,” grunted Lugg. “We can warn the king. The moles are on their way, but the boat can get there before them.”

The burrow widened into a network of tree roots, where the air tasted fresher. They must be near the surface.

“Not far now, Juniper,” whispered Urchin.

“Spread out,” said Larch. “It’s safer to come out different ways. We won’t be far from each other. Quickly!”

Urchin dived under a tree root and scrabbled forward, hearing Juniper’s struggling breaths behind him. Paw by paw he scrambled up through the tree roots, turned to extend a paw to Juniper, and finally stood up. He was far beyond the Fortress, under the icy sky. A pale arc of moon rode high above them, and starlight sparkled on a land already bright with snow and silver.

For the first time, the reality of the snow dawned on Urchin. Flakes tumbled softly, slowly to the earth. They melted on Cedar’s cloak as she slipped from the burrow, on Flame’s whiskers as he lifted his face to the sky. Watching from one side to the other, ears and nose twitching, Urchin and Juniper scurried forward. Lugg came after, and gradually they gathered together again, keeping their cloaks wrapped tightly about them for warmth and secrecy, pattering steadily up to the top of the dunes.

Somebody was moving nearby. Urchin didn’t dare turn his head, didn’t want to make himself conspicuous. There was somebody ahead of him, too.

“There are other animals about,” he whispered.

“I know,” said Larch, hurrying on. “They’re all on our side. They’ll rally to us if we have to fight. Since you came, they’ve had hope. Partly it’s because Cedar told me what you said, about how your captain on Mistmantle encouraged you to talk to the other animals, and tell them what was really going on. We’ve been doing that, since you came. But more than that, it’s you yourself, Urchin. Just knowing there’s a Marked Squirrel on the island gives them courage, especially knowing that he might be Candle and Almond’s son. It’s not only the Larchlings. Most of the animals have only put up with Silverbirch and Smokewreath because they were terrified. You’ve given them hope.”

“It’s getting lighter,” said Cedar. “Faster!” Hushed and hurrying, helping each other up the stony and slippery paths, they finally struggled to the top of the dunes.

By the pale rising light, Urchin looked down on the harbor and thought again that it was the loveliest place on the island. A stately ship still stood at anchor, tall and noble in the dawn. The small boat waited for them, very still on the water.

Our boat! thought Urchin with a thrill of excitement.

“Nearly there!” said Larch, and holding each other’s paws for balance, they rushed down the dunes toward the bay. Then a tug on his paw flung Urchin to the ground.

“They’ve found us!” gasped Juniper.

All of them lay flat in the sand and sharp grass. Urchin raised his eyes to see armed figures running onto the beach, lifting the bows from their shoulders, bending them, setting the arrows—he pressed his head down.

“Crawl backward!” hissed Cedar. “Burrow!”

Keeping his head down, Urchin crept backward into the nearest burrow.

Flights of arrows shrieked through the air. Juniper and Flame were on either side of him as they huddled as far back as they could in the shelter of a shallow, sandy burrow, where Cedar was already prodding at the walls, searching for a tunnel and not finding one.

“The only way out is the only way in,” she said. “Stay still and hope. Where are Lugg and Larch?”

Flame had flattened himself against the sandy earth. “Hiding in the undergrowth opposite us,” he said. “They’re safe.”

Voices were calling out, drawing nearer, barking orders, asking questions. Urchin drew in his shoulders as if he could make himself small enough to be invisible. Silently, they drew their swords and pressed backward. His own heartbeat and Juniper’s breathing sounded to Urchin as loud as a drumbeat. Juniper stifled a cough.

As animals tramped through the dunes, swishing through coarse grass, calling to each other, a sudden rage rose in Urchin, helpless simmering fury at the unfairness of it all. Why couldn’t they leave him alone? He’d never asked to come here. All he wanted was to go home!

He took a deep breath. There was no point in thinking like that. Never mind if this was fair or unfair, it was real, that was all. Vividly, he remembered something he had once said to Needle, on another shore.

There’s more that I have to do. And more that I have to be. It’s not as if you can do one special thing, and that’s it. It’s what you go on being that matters.

He was here. He couldn’t change that. He had talked about doing something to help this island, and Flame had said that he would, if he was meant to. Perhaps it was only by being here, hiding and hunted, that he could see what to do. His father had died for this island. He might be able to make a difference to it now, to continue the work his father had begun.

Paws hurried about above them. He heard guards calling to each other.

“If you find the Marked Squirrel, don’t kill him,” said a voice. “The king wants him for Smokewreath—if the king’s happy, Smokewreath’s happy, and then everyone’s happy. Except the Marked Squirrel. Oh, and Commander Cedar. The king wants her alive. By the time he’s finished with her, there’ll be nothing left for Smokewreath.”

Urchin rolled over and hugged his knees, gazing ahead of him. There was only one thing to do. He stood up, taking off his cloak and brushing soot from his fur so his true color would show clearly.

“Get down!” ordered Cedar.

Urchin took Juniper’s paw. “Thanks for everything you’ve done,” he said. “For staying with me. I wish you were my brother—you

are

my brother, as far as anyone can be. Cedar, Flame, thanks for everything.”

“We’re not beaten,” said Cedar. “Get down.”

“They’ll be here soon,” said Urchin. “Sooner or later the chances are they’ll find me, and that means they’ll find you, too. I’m the one Smokewreath wants. If I give myself up, they won’t come looking for you.”

Juniper gripped his paw. His eyes glowed with an intensity that astounded Urchin and frightened him.

“No!” he snarled. “Don’t you dare! I came all this way to save you, and you think you can just walk out and get yourself killed!”

“If I really am meant to do something for this island, maybe this is the way,” said Urchin.

“Don’t be stupid,” said Juniper. “How can this help anyone?”

“I just think it might,” said Urchin wretchedly. Juniper was making it much harder. “This will give you a better chance to get away and save Mistmantle. Silverbirch’s moles are on their way. If I go to the king, freely, now, you can slip down to the bay, take the small boat, and get home before the moles. Warn Crispin. You too, Cedar, it isn’t safe for you here. They’ll be so busy dragging me off to Smokewreath, they’ll even forget to hunt for you, at least long enough for you to get away. You can have my place in the boat. Tell them what happened to me, and tell them what Whitewings is like. Give everyone my love—Crispin, Padra, everyone. Hug Apple for me, and tell her I said thanks for everything.”

Cedar looked beseechingly up at Flame. “Tell him he’s wrong!” she pleaded. “Urchin, I won’t let you.”

“You can’t stop me,” said Urchin.

“I will,” said Juniper. He confronted Urchin with fierce eyes and outstretched claws. “Don’t you take one more step. I’ve seen that dungeon Smokewreath works in, and it’s foul, and I won’t let you go there. What if he really can make evil magic out of you? Magic that can endanger Mistmantle? Had you thought of that? Tell him, Brother Flame!”

But Brother Flame’s eyes were heavy with sorrow. He laid his thin paws on Juniper’s shoulders. He looked wise and strong, and reminded Urchin of Fir.

“Urchin is right,” he said sadly. “I wish he weren’t. He has seen the thing he must do, and he will do it. Whatever Smokewreath can do, he can never make evil magic out of such a true heart. The Heart is stronger than all Smokewreath’s sorcery. The Heart creates, evil can only destroy. Urchin, we’ll give time for Cedar and the others to get away; then if the Larchlings can rescue you, we will. Perhaps this will make the islanders stand up to Smokewreath at last.”

“Thanks,” said Urchin, but there didn’t seem much hope. He lowered his head. “May I have your blessing?”

“The Heart keep you, warm you, and receive you,” said Flame. “And forever may the Heart be with those you love, Urchin of the Riding Stars.”

Juniper hugged him, then Flame, and at last Cedar embraced him like a mother before she reached into the satchel under her cloak.

“Your mother’s bracelet,” she said. “Do you want to take it with you?”

He looked at the pale circle on her paw and touched it gently. It mustn’t fall into Smokewreath’s paws, but it was good to see it once more.

“Take it to Crispin, please,” he said. “Ask him to keep it for me.”

It hurt that he couldn’t say more. But there wasn’t time, and no words were strong enough. Juniper could have become a tower squirrel too, and they could have worked together, taught each other new skills, skimmed stones, and messed about in boats—that couldn’t happen now. He wriggled to the burrow entrance.

“Heart keep me,” he whispered as he stepped from the burrow. “Father, Mother, if you can see me, help me.”

He crept, staying close to the ground, until he was at a safe distance from the burrow where his friends sheltered, and quite alone. Then he stood up, squared his shoulders, and lifted his head. Finally, he left his cloak lying on the ground and gave his fur one more brushing, so that everyone could see who he was. Climbing the dunes, he held up his paws. The singing of arrows stopped.

“I am the Marked Squirrel,” he called out, “Urchin of the Riding Stars, Companion to Crispin the King. Do you want me alive?”

EAR THE TOP OF THE DUNES

EAR THE TOP OF THE DUNES

, he turned to look about him. At every second he had expected rough paws to grab at him, but nobody had touched him.

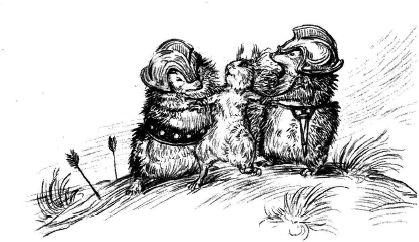

All about him, hedgehogs and squirrels stood and stared. Those who didn’t wear helmets were glancing uncertainly at him, then at each other, as if they didn’t know what to do. Wondering if this were all a dream, he marched on. He wished somebody would do something. It was as if they were watching to see if his courage would hold. It was almost a relief when two hedgehogs ran to his side and took hold of his arms and shoulders, but it felt as if they wanted to apologize for arresting him.

They marched him onward. Other animals gathered around them and followed, but it seemed to Urchin that he was the one leading the way until they stood at the highest point on top of the dunes, the point from which he could see as far as the Fortress and beyond it to the crags. On this bare winter day, the Fortress was clearer than ever.

The hedgehogs holding him were gaining confidence. They’d arrested the Marked Squirrel and he wasn’t resisting, and, gripping his arms tightly, they quickened the pace. Archers and guards, keen to share the glory, ran to help them. Paws grabbed at Urchin, elbowing each other aside to reach him, pushing and dragging him.