U.S.S. Seawolf (11 page)

Authors: Patrick Robinson

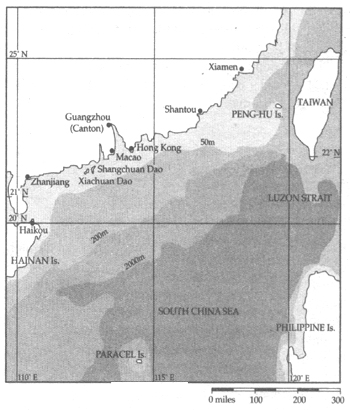

Pearson estimated they would be right off Canton (Guangzhou in modern Chinese) by first light on July 1. Meanwhile, in company with

Xia III

, they charged through the night on a head of steam generated by Thompson’s sweet-running pressurized water reactor (PWR).

The other major head of steam in Chinese waters that evening was generated by a fuming Admiral Zhang, who glowered across at the lazy, gaff-rigged junks while he made the short ferry journey home to Gulangyu. No wreckage had been found, no one had reported any kind of a hit or oil slick, and his captains had been driven to the conclusion that no American nuclear boat was tracking the new

Xia

at this time. Each of the surface warships had kept up the barrage around the new Chinese submarine for a total of two hours, and had blown upward of 200 depth charges and the same number of ASW mortars. Result: a big fat nothing.

Zhang did not believe them. At least, he did not believe their conclusion. But he did believe they had tried and missed. Which was a personal blow to him, because in his heart he had truly hoped one of those depth charges would have blown a big hole in the hull of USS

Seawolf

. The fact that they had not done so merely meant they had

not fired one close enough. It did not mean

Seawolf

was not there. It meant that she was devilishly hard to find, and that she was being driven by a master, with a brilliantly competent crew.

0900. Friday, June 30

.

Office of the National Security Adviser

to the President

.

At one minute past the hour Admiral Morgan let fly, ignoring as ever the state-of-the-art White House telephone system.

“

COFFEE

!” he bellowed.

At one minute and eight seconds past the hour, his door opened briskly and Kathy O’Brien walked in.

“Good. Nice and quick. The way I like it. Bit more practice and you’ll be just fine.”

The admiral did not look up.

“I am afraid that even I, even at my most devoted, cannot produce coffee the way you like it in under ten seconds.”

“Right,” he said, still not looking up. “Three buckshot and stir,

s’il vous plaît

…”

The admiral had taken to the use of occasional French phrases ever since their perfect weekend in Paris in April. Kathy hoped that one more visit would persuade him that the

t

in

plaît

was in fact silent.

“Oh, Great One,” she said, “whose mind operates only on matters so huge the rest of us mortals can’t quite get it…I bring messages from the military.”

And she scuffed his papers all over the place and told him that she loved him, even though she had only just got to work, whereas he had been at his desk since 0600.

“Where’s my coffee?” he wondered, grinning, faking absentmindedness.

“Christ, you’re impossible,” she confirmed. “Listen, do

you want me to get Admiral Mulligan on the phone or do you not? His assistant called two minutes ago and asked you to get back to him secure.”

“Of course, and hurry, will you? Goddamned women fussing about coffee when the country’s far eastern fleet may be on the brink of destruction.”

“It’s you who stands on the brink of destruction,” retorted Kathy as she marched out of the door. “Because I may of course kill you one day.”

“Now what the hell have I done?” the admiral asked the portrait of General Patton. “And where’s the goddamned CNO if it’s that urgent?”

The pastel green telephone tinkled lightly, grotesquely out of character with its master. “Faggot phone. Faggot ring. I’d rather listen to a goddamned battleship’s klaxon.” He picked it up.

“Hey, Joe. What’s hot?”

And then Arnold Morgan went very quiet as the Navy’s top man in the Pentagon outlined the recent uproar in the Taiwan Strait.

“Taipei came in right away when it started, sometime before lunch today. They reported a small Chinese battle fleet about twenty miles off their southwestern naval base at Kaohsiung, hurling hardware every which way.

“The Taiwanese have a pretty big air base down there at P’ingtung and they sent up a couple of those Grumman S2E turbo trackers…worked the place over from twenty-five thousand feet, reported a lot of action, ordnance flying around, mortars and depth charges. They reported no missiles over their land, and they were not fired on.

“The only thing that surprised them was a big ICBM submarine, heading southeast, probably out of Xiamen, on the surface, flying the pennant of the People’s Liberation Army/Navy. They didn’t report any other submarine in the area, either on or below the surface. Which I thought was surprising, because the Taiwanese have

turned those Grummans into real specialist ASW aircraft—new sensors, new APS 504 search radar, sonobuoys, Mark 24 torpedoes, depth charges, depth bombs, the lot. If there was another big sub in the Chinese ops area, they’da surely found it. Hell, we’ve sold ’em all our latest stuff. They have, legally, nearly as much as the Chinese stole…”

“And your conclusion, CNO?”

“I don’t know where our man is.”

“Well, they plainly haven’t hit him, or half the world would know by now.”

“Right. According to Taipei, the bombardment was over by fourteen-thirty.”

“So I guess he’s still there, lurking.”

“Well, he could hardly have followed them into the Taiwan Strait, Arnie. Not without a big risk. Too shallow. Maybe he hung around to the south, then picked up the

Xia

on her way to her ops area. I presume she’s conducting sea trials.”

“And our people believe she’s going to be based at the Southern Fleet headquarters at Zhanjiang, Joe…so she’s plainly on her way south, probably right off that base.”

“I guess we oughtta be grateful we’re undetected. Anyway, I’m just checking in. Thought you’d wanna be kept up to speed.”

“I’m grateful, Joe. By the way, you know my conclusion? The Chinese

believe

we’re out there watching. And if they get half a chance, I think they may actually hit our ship. And then say how goddamned sorry they were, but we really should have told them if we wanted to go creeping around their coastline.”

“Wouldn’t that be just like them? Devious Orientals.”

“Chinese pricks. ’Bye, Joe.”

Admiral Mulligan was oblivious to the compliment. The National Security Adviser never said good-bye to anyone except the CNO. He was too busy, too preoccupied to bother with that. Even the President was occa

sionally left holding a dead phone while his military adviser charged forward with zero thought for the niceties of high office.

“He just don’t pay no one no never mind,” was the verdict of Arnold’s permanently cowed chauffeur, Charlie. “Ain’t got time, man…ain’t got no-o-o-o time.”

020130JULY06

.

20.50N 116.40E South China Sea

.

Speed 25. Depth 200

.

Course 250

.

Lt. Commander Clarke had the conn as they ran through deep water more than 100 miles south of the Chinese Naval Base at Shantou. The

Xia

was showing no signs of stopping, turning, or slowing down, just heading resolutely southwest down the coast.

Judd Crocker’s team assessed that her ops area would be somewhere out around 20.25N 111.46E, east-southeast of Zhanjiang, Southern Fleet HQ. And there she would doubtless dive, before heading out to begin her deep submergence trials. But there she would also probably come up occasionally, access her satellite, report defects if anything urgent popped up, and perhaps rendezvous with a surface escort.

The first time she did that, night or day, Judd Crocker would personally take

Seawolf

deeper and slide with the utmost stealth under her keel. Dead under. Accurate to a few inches, unseen, undetected, pinging sonar all along the hull, drawing an automatic picture on the fathometer trace; the one that would tell the U.S. Navy scientists back in Washington whether or not China had the capacity to hurl a big missile at Los Angeles and hit it.

By any standards, Captain Crocker had been charged with the most stupendous task. Spying on a foreign submarine, listening and watching, recording and tracking, was one thing. Trying to get a real close look, straight up

her skirt, as it were, was entirely another, even more so without being caught doing it. But it had been done before, notably by the Brits in the Barents Sea at the height of the Cold War in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Seawolf

’s Southern Ops Area

One of their COs got very close underneath a 10,000-ton Soviet Delta-class nuclear boat designed to carry submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBM), and took soundings upward along the entire submerged part of the hull. He got away with it, too…but to complete the measurements he had to raise his periscope 100 yards off her port quarter for the photographs that would reveal the above-water height of the missile tubes.

He eased the periscope up, the tip of it only 18 inches above the flat, calm surface. His aim was a seven-second, three-exposure snatch. But an oil smear wrecked all that.

To his horror, he saw an image too badly blurred for camera work. And that meant at least a 30-second delay while it hung out to dry in the hostile Russian air.

To his further horror, as the image cleared he saw a small crowd gathering on the Delta’s bridge. And they were pointing straight at his periscope, and his recording camera, the eyes of the West, the ultimate intruder.

A massive three-day ASW hunt ensued, conducted by most of the Russian Northern Fleet, but the British commanding officer essentially ran rings around the Soviets and got away with the required measurements scot-free.

Very few American commanders knew that story, and none of them knew the man who did it. But not many COs had been tasked with repeating the maneuver, as Judd Crocker now was.

Happily he was sound asleep as Linus Clarke sped southwest, astern of the

Xia

, covering 25 nautical miles every hour.

The watch changed at 0400. Captain Crocker came back into the control room, and Clarke handed over formally.

“You have the conn, sir.”

“I have the conn.”

Both men were surprised at the noise the new Chinese boat was making. At 25 knots you could hear her for a long way, but then she was traveling fast for her, whereas

Seawolf

was merely cruising, just a little over half-speed, right in her quarry’s deaf stern arcs.

As Admiral Zhang had remarked that morning, “If only we could find a way to adapt that American satellite technology we acquired from them. But alas, we seem doomed to failure on that one. As I seem doomed to failure to find and ‘accidentally’ sink the American prowler. They cannot fool me, however. I know they’re out there, still tracking my very beautiful new

Xia

.”

It was 4:00

A.M.

now and the C-in-C could not sleep.

He remained alone in his study, overlooking the water. He was still in uniform, but he wore no shoes. Outside it was raining hard, with the onset of the South China monsoon season. Tomorrow there would be heavy mist out over the water.

But for now he just pored over his chart. The one that gave him all the depths after the 100-meter line south of Zhanjiang, the one that marked out clearly the operations area of

Xia III

.

At 0430 he tapped in a message to Zu Jicai, the Southern Commander, instructing him to place all 14 of his operational destroyers and frigates on one hour’s notice to leave for the

Xia

’s ops area. He instructed each ship to be on full ASW alert, laden to the gunwales with depth charges, depth bombs, torpedoes and, for those equipped with launchers, ASW mortars.

He ordered a satellite message to be delivered to the

Xia

’s CO that he was to surface immediately if he detected even the slightest suggestion of an American nuclear boat, and to report instantly to HQ. That way he could get his ASW fleet out there fast. That way the

Xia

would be safe. Even the American gangsters would not dare to hit her while she was on the surface in full view of the satellites.

He paced the room, slapping his left palm with his big ruler, running his fingers through his hair. “The trouble is, I have to rely on the American CO making a mistake. And since he is driving the top submarine in the American Navy, he probably makes very few.

“But if he does, I’ll get him. And what a moment that would be.” And in his mind he imagined the moment when he would speak to the C-in-C of the American military, sympathizing with the terrible loss of

Seawolf

.

But Mr. President, we are so sorry. However, if you send a big nuclear boat into any part of the South China Sea, especially so close to our coastline, to spy on our perfectly legal naval operations…then accidents can

sometimes happen. What more can I say? If only you had told us you were coming, we would have been so much more careful

.

Perhaps you will in the future. Again, our profound apologies, and deepest sympathies to the families of the brave men who died

.

And for the first time in this longest of nights, a thin smile flickered across the broad face of the Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Liberation Navy.