Various Pets Alive and Dead (16 page)

Read Various Pets Alive and Dead Online

Authors: Marina Lewycka

She rummages in her drawer for a T-shirt with a suitable slogan, which she keeps for such occasions. Ah! This is the one for a social worker! ‘

Be realistic – demand the impossible

.’ She slips it on over her head, and notices with regret that her breasts, which used to push out ‘r’ and ‘t’ now hover above ‘m’ and ‘h’. (Her mother had been right about the ‘brazeer’, as about so much else.) A quick comb-through of her hair, and she’s already on her way downstairs when the doorbell rings.

Mr Clements is a young plain-spoken Yorkshireman with a pleasant ruddy face framed by thick fair hair that sticks straight up from his forehead and blond stubble around his chin, which may be destined for a beard. He looks a bit like Clara’s previous boyfriend, Josh, who disappeared off the scene in circumstances which Clara refuses to discuss, and this causes Doro to feel a twinge of dissatisfaction with her daughter, who has not yet settled down with a suitable partner and shows no signs of producing the grandchildren that she yearns for.

‘Hiya, Mrs Lerner. How’s it going?’

‘Fine.’ She resents being called Mrs when she’s not married, and Lerner, which is Marcus’s name, instead of Marchmont, which is hers. ‘Would you like a cup of tea?’

‘Ta, duck. Milk but no sugar.’

He seats himself at the kitchen table and shrugs off his blue denim jacket. Just to show him she’s not a person to be trifled with, she hands him his tea in a cracked and chipped ‘

BATTLE OF ORGREAVE

1984

VETERANS

’ mug, a relic of the miners’ strike.

‘Blimey, that was a long while ago.’ He takes a long sip and studies it with interest. ‘I was just a lad. I remember, my dad got arrested, and my mam thought it were the end of the world. But it spurred me on to do summat different with my life, instead of just going down the pit like everybody else.’ He pulls a file out of his briefcase. ‘So how’s Oolie-Anna been getting on at Edenthorpe’s?’

‘Fine.’

Mr Clements nods, ticks a paper in his folder, and she’s grateful that he resists pointing out that the job was his idea, which she had strongly opposed at the time.

‘Yes, she’s a right character. Edna says she has them all in stitches.’

‘She enjoys the company,’ Doro admits grudgingly. She still finds it disconcerting to think of Oolie having relationships outside the family.

‘The next stage we have to think about is independent living, Mrs Lerner. A flat of her own.’

‘She’s not ready for it,’ Doro snaps back.

Mr Clements shuffles the papers in his folder and takes another sip of tea.

‘You’re right to be concerned, Mrs Lerner. But in the long term it’ll be better for everybody if Oolie-Anna can spread her wings and learn to fly. Don’t you agree?’

His cheeriness is relentless. Doro knows she’s being manoeuvred into saying yes.

‘We all want what’s best for her, Mr Clements, but we have different interpretations of her needs.’

‘So can I take that as a yes?’

‘No, you can’t. I know Oolie-Anna a lot better than you do.’

She stares furiously across the table at the pink young face.

‘We have to plan for the possibility of kiddies with Down’s outliving their parents nowadays.’ His tone is unwaveringly upbeat. ‘We want to avoid the situation where they lose not just their parents but their familiar living environment at the same time. So we like to start the process of separation early –’

‘You think Marcus and I are going to croak any minute now?’ she interrupts, feeling the heat build up in her cheeks.

Mr Clements, unruffled, drives home his advantage. Dealing with client rage is all part of his training.

‘That’s not what I’m saying, Mrs Lerner. On the contrary, we need to plan as far in advance as possible so we’re not caught out when … when you and your husband are no longer able to care.’

He doesn’t raise his voice or deviate from his script. She wants to throttle him.

‘It’ll help if you can confront your fears, Mrs Lerner. If there’s any particular worries you have, we can discuss them. It’s natural for you and your hubby to feel concerned …’

What else does he know, she wonders? Do the social services files of 1994 cross-refer with the police records of the day?

‘If it’s because we’re not married, we are actually planning –’

‘Your ages are the main factor we have to think about, Mrs Lerner – though of course that’s often the case with Down’s kiddies.’

Doro resists the impulse to vomit all over his briefcase.

‘Oolie-Anna is not a kiddy.’

‘That’s just my point, Mrs Lerner. So shall I book us another meeting for next week, when you and your hubby’ve had a chance to talk it over?’

He’s persistent, this boy.

‘No. That won’t be necessary.’

She stands and frowns until he rises to his feet.

‘Well, I’d better be getting along. Thanks for the tea, Mrs Lerner.’

He smiles, patient and confident. He thinks he’s making progress.

After he’s gone, she sits at the kitchen table for several minutes. For some reason she feels utterly drained. On the wall in front of her, a clock is ticking away above a faded group photograph of the Solidarity Hall commune, taken in the back garden. Megan is in the photo, with Oolie, so it must have been sometime between 1985 and 1988. They all look so ridiculously young, the women with long untidy hair, the men with fluffy sideburns and moustaches, the children scruffy and mischievous. Where have all the years gone? She wishes she hadn’t been so aggressive with the young social worker – he didn’t deserve it, he means well, and actually he’s quite good at his job. She knows that her resistance to Oolie moving away must appear irrational to him, but she isn’t ready to unpack the carefully put-away past.

Not yet.

Marcus comes down and slips an arm around her shoulder – he must have heard the front door click.

‘Okay?’

‘Okay. How’s the book going?’ she asks.

‘Great. I’ve finished the analysis of the left and I’m just about to start on the role of the women’s movement.’ His eyes brighten.

‘Mm.’ She sits forward, trying to look interested, but her mind is still replaying the conversation with the social worker, snagging at the points at which she should have said something different.

‘I’m coming to realise just how important feminism is in the history of our movement.’ He glances up at Doro, and his eyes soften. ‘Maybe

you

could write that chapter, love. From the woman’s perspective.’

Doro tries to think about feminism, but all that comes to mind is an image from long ago of a handful of Moira Lafferty’s auburn hair clutched in her fist. She reaches out and squeezes his hand, realising she’s being offered a great honour, but the earlier feeling of exhaustion and resentment has congealed like cold porridge around her heart.

‘You write it, dear. I’m sure you know much more about it.’

He wanders through into the kitchen to put the kettle on.

‘So how d’you get on with the social worker?’

Doro gives the leg of the chair where Mr Clements was sitting a petulant kick.

‘He’s determined to get Oolie into that bloody sheltered housing scheme. He’ll go on and on till he gets his way.’

‘That might not be such a bad idea, you know, love.’

He fishes in his cup for the submerged tea bag, and squeezes it with his fingers.

‘Have you forgotten the kids throwing bricks at her, Marcus? Have you forgotten the fire? She’s too vulnerable. No.’

What she doesn’t say is that out of all the chaos, fun and disappointment of the commune, Oolie is her surprise accomplishment, even more than Clara and Serge, the unsteady twinkling star who illuminates those years.

By the time Serge gets into the disabled loo to place his stop order, he’s already £40,000 down.

Back at his desk, he starts to feel panicky about the scale of his losses. But the little brown cockroach that will see him right is nestling in his pocket. He’ll copy it on to his hard drive when he gets home. The more he thinks of it, the more it seems like a sign: the Mersenne prime; the wanton tango of the market; the cockroach capsule of information. They must be linked together.

He doesn’t believe in destiny or karma or any other mystical mumbo-jumbo – the commune inoculated him against all that – but he does believe in patterns. He’s seen them with his own eyes, intricate beautiful patterns, configured out of apparently random events. He knows that chance is seldom as random as it seems – chance and its close cousin, risk.

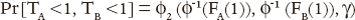

What is the risk that Chicken will come back, looking for his lost memory stick? What is the risk he’ll find out if Serge downloads his data? Will the risks be offset if he sets up a decoy, by dropping the stick next to someone else’s desk? Or is it best to gamble that Chicken won’t find out at all? Actually, there is a formula for figuring out these complex risks. It’s the Gaussian copula, beloved of derivatives analysts.

Thinking about the copula brings to mind copulation, and his thoughts stray back to Maroushka. The chances of them ending up in bed together, he reckons, are about 50 per cent. If Maroushka ends up in bed with him, though, then the chance that he will end up in bed with her is 100 per cent. If Maroushka ends up in bed with Chicken, however, his chances are greatly reduced, but still not zero (there is, after all, the possibility of a threesome, though the thought of a threesome with Maroushka and Chicken is distinctly scary). The risk of two people in bed together being struck by lightning is infinitesimal. But if one is struck, the risk to the other person in the same bed jumps to, say, 99 per cent, while the risk to the person sleeping on their lonely own in a faraway bed is still almost zero. On the other hand, if one person has a heart attack in bed, the risk to the other person (or people) in the same bed is still much the same as it was before. A heart attack and a lightning strike are different kinds of risks, yet neither of them comes completely out of the blue.

Now let’s jumble up these risks and repackage them. Let’s put together a bundle which includes, say, the lightning strike, him and Maroushka in bed, and Chicken having a heart attack. The chances of them all happening are still pretty low, because of the lightning strike. But if you take out the lightning strike, what are you left with? Serge hasn’t a clue – and the truth is, neither have most people who trade in risk-based derivatives.

Okay, so forget about lightning strikes and threesomes, and think mortgages, car loans, hire-purchase agreements – these are the sorts of risks that preoccupy the guys on the FATCA Securitisation desk. They’re all hard at it, tapping at their keyboards, late on Friday afternoon. What’s the risk that someone will notice he’s not participating? He stares at his screens, and attempts to engage with the shifts and turns of the market, but his heart is hammering so much that he soon gives up and takes the lift up to the cafeteria for a calming cup of chamomile and ashwagandha tea.

Outside the cafeteria window a bank of cloud, electric blue, is massing over the city. A few heavy raindrops spatter against the pane like falling stars. Far below, people the size of ants are unfurling umbrellas, hurrying into cabs and buses, rushing to get home before the storm breaks. In an hour or so, he will be down there too, hurrying towards the tube with the mysterious contents of the cockroach capsule in his pocket. A rumble of thunder spreads and dissipates into the air. Somewhere, there has been a lightning strike.

It’s raining in Sheffield too, as Clara stands at the checkout queue in Waitrose on Friday evening, piling her purchases on to the belt, wondering whether it’s bad to have chocolate mousse

and

tarte au citron

and

cheesecake

and

two bottles of prosecco. No, it’s not bad. Because I’m worth it. And because I need cheering up.

‘Cash or card?’ asks the girl.

She pulls one of Ida’s twenties out of her pocket, and takes her feast back home.

The theft of her purse has soured her mood all week, like a bad taste in the mouth. In her mind, she’s still replaying the scene where Jason knocked against her as he ducked under her arm to get away on Monday afternoon. That must have been when it happened. Talking to the class next day, she’d given Jason the Look, but he’d avoided her eye and kept his head down. Mr Kenny’s description of Jason sticks like gum on the floor of her mind, filthy but stubborn.

When she asked Mr Philpott whether she’d dropped it in the boiler room, all he offered was, ‘Who steals my purse gets trashed.’

Mr Gorst/Alan twinkled sympathetically, and asked if she wanted to call the police. She shook her head. It was her fault – she should have left it in her locker in the staffroom. She didn’t blame the kids, she just said her purse had vanished from her bag, and she appealed to the kids’ better nature.

‘If anyone would like to return something to me, I won’t say anything and I’ll be very happy and grateful. You can just leave it in my desk drawer. If one of you knows what I’m talking about, you know the right thing to do.’