Vegetable Gardening (99 page)

If your soil is dry, water well, and let it sit for a few days before digging. Then, to determine whether your soil is ready to turn, take a handful of soil and squeeze it. The soil should crumble easily in your hand with a flick of your finger; if water drips out, it's too wet.

Don't work soil that's too wet. Working soil that's too wet ruins the soil structure — after it dries, the soil is hard to work and even harder to grow roots in.

Don't work soil that's too wet. Working soil that's too wet ruins the soil structure — after it dries, the soil is hard to work and even harder to grow roots in.

The easiest way to turn your soil, especially in large plots, is with a

rototiller

(or

tiller,

for short). You can rent or borrow a tiller, or if you're serious about this vegetable-garden business, buy one. I prefer tillers with rear tines and power-driven wheels because you can really lean into the machines and use your weight to till deeper. If you have a small (less than 100 square feet) vegetable plot, consider using a minitiller (see Chapter 20 for more details on this tool) or hand dig it if you're up for a little exercise.

If you use a rototiller, adjust the tines so the initial pass over your soil is fairly shallow (a few inches deep). As the soil loosens, set the tines deeper with successive passes (crisscrossing at 90-degree angles) until the top 8 to 12 inches of soil are loosened.

To turn your soil by hand, use a straight spade and a digging fork. You can either dig your garden to one spade's depth, about 1 foot, or

double dig

(that is, work your soil to a greater depth), going down 20 to 24 inches. After turning the soil, level the area with a steel rake, breaking up clods and discarding any rocks. Although double digging takes more effort, it enables roots to penetrate deeper to find water and nutrients. If you're double digging, dig the upper part of the soil with a straight spade to remove the sod and loosen the

subsoil

(usually any soil below 8 to 12 inches) with a spade. Replace the original topsoil often when you loosen the subsoil.

Don't overtill your soil. Tilling to mix amendments or loosen the soil in spring or fall is fine, but using the tiller repeatedly in summer to weed or turn beds ruins the soil structure and causes the organic matter (the good stuff) to break down too fast.

Don't overtill your soil. Tilling to mix amendments or loosen the soil in spring or fall is fine, but using the tiller repeatedly in summer to weed or turn beds ruins the soil structure and causes the organic matter (the good stuff) to break down too fast.

Making Your Own Compost

Making your own compost is a way to turn a wide array of readily available organic materials — such as grass clippings, household garbage, and plant residue — into a uniform, easy-to-handle source of organic matter for your garden. Even though finished compost is usually low in plant nutrients, composting enables you to enrich your soil in an efficient, inexpensive way. You can add organic matter that isn't decomposed to your soil and get a similar result, but most people find that dark, crumbly compost is easier to handle than half-rotten household garbage — yuck.

A

compost pile

(a pile of organic matter constructed to decompose) can be free standing or enclosed and can be made any time of year. However, you'll have the most organic matter in summer and fall when decomposition occurs faster due to the warm weather.

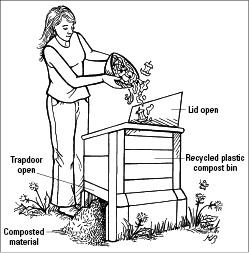

Wire fencing makes a good container because it lets in plenty of air. You also can purchase easy-to-use composters at garden centers or through mail-order catalogs (see Figure 14-3). Some composters simplify the turning process (see "Moistening and turning your compost pile" later in this chapter), because they rotate on swivels or come apart in sections or pieces. They're easy to use, but usually aren't large enough for the amount of material produced in a large garden. You can build your own composter as well.

In the following sections, I show you how to build, moisten, and turn a compost pile; I also warn you about materials that should never, ever go into a compost pile.

Figure 14-3:

Easy-to-use containers make composting simple.

Building a compost pile

Building a good compost pile involves much more than just tossing organic materials in a pile in the corner of your yard, though many people (including me at times) use this technique with varied success. Because, you know, everything does eventually rot. But to compost correctly, you need to have a good size for your pile, add the right types and amount of materials, and provide the correct amount of moisture.

Here are the characteristics of a well-made pile:

Here are the characteristics of a well-made pile:

It heats up quickly — a sign that the decay organisms are at work.

It heats up quickly — a sign that the decay organisms are at work.

Decomposition proceeds at a rapid rate.

Decomposition proceeds at a rapid rate.

The pile doesn't give off any bad odors.

The pile doesn't give off any bad odors.

The organisms that do all the decay work take up carbon and nitrogen (the stuff they feed on and break down) in proportion to their needs.

The organisms that do all the decay work take up carbon and nitrogen (the stuff they feed on and break down) in proportion to their needs.

You can easily come up with the correct amounts of materials for a compost pile by building the pile in layers. Just follow these steps:

1. Choose a well-drained spot in your yard.

If you build your compost pile on a naturally wet spot, the layers will become too wet and inhibit the decomposition process.

2. Create a 4- to 6-inch layer of "brown" materials that are rich in carbon.

These brown materials include roots and stalks of old plants, old grass clippings, dried hay, leaves, and so on. The more finely chopped these materials are, the more surface area that decay organisms can attack, and the faster the materials decompose.

3. Add a thin layer of "green" materials that are high in nitrogen.

Green materials include green grass clippings, kitchen vegetable scraps, a 2- to 4-inch layer of manure, or a light, even coating of blood meal, cottonseed meal, or organic fertilizer high in nitrogen (see Chapter 15 for more on fertilizers).

4. Repeat these green and brown layers (Steps 2 through 3) until the pile is no more than 5 feet high.

If a pile is higher than 5 feet, too little oxygen reaches the center of the pile, enabling some nasty anaerobic decay organisms to take over and produce bad odors; I hate that. Five feet is a good maximum width for the pile as well.