Vintage Sacks (12 page)

Driving back from the ranch was a stimulating, at times terrifying, experience. Now that Bennett was getting to know me, he felt at liberty to let himself and his Tourette's go. The steering wheel was abandoned for seconds at a timeâor so it seemed to me, in my alarmâwhile he tapped on the windshield (to a litany of “Hooty-hoo!” and “Hi, there!” and “Hideous!”), rearranged his glasses, “centered” them in a hundred different ways, and, with bent forefingers, continually smoothed and evened his mustache while gazing in the rearview mirror rather than at the road. His need to center the steering wheel in relation to his knees also grew almost frenetic: he had constantly to “balance” it, to jerk it to and fro, causing the car to zigzag erratically down the road. “Don't worry,” he said when he saw my anxiety. “I know this road. I could see from way back that nothing was coming. I've never had an accident driving.”

40

The impulse to look, and to be looked at, is very striking with Bennett, and, indeed, as soon as we got back to the house he seized Mark and planted himself in front of him, smoothing his mustache furiously and saying, “Look at me! Look at me!” Mark, arrested, stayed where he was, but his eyes wandered to and fro. Now Bennett seized Mark's head, held it rigidly toward him, hissing. “Look, look at me!” And Mark became totally still, transfixed, as if hypnotized.

I found this scene disquieting. Other scenes with the family I had found rather moving: Bennett dabbing at Helen's hair, symmetrically, with outstretched fingers, going “whoo, whoo” softly. She was placid, accepting; it was a touching scene, both tender and absurd. “I love him as he is,” Helen said. “I wouldn't want him any other way.” Bennett feels the same way: “Funny diseaseâI don't think of it as a disease but as just me. I say the word âdisease,' but it doesn't seem to be the appropriate word.”

It is difficult for Bennett, and is often difficult for Touretters, to see their Tourette's as something external to themselves, because many of its tics and urges may be felt as intentional, as an integral part of the self, the personality, the will. It is quite different, by contrast, with something like parkinsonism or chorea: these have no quality of self-ness or intentionality and are always felt as diseases, as outside the self. Compulsions and tics occupy an intermediate position, seeming sometimes to be an expression of one's personal will, sometimes a coercion of it by another, alien will. These ambiguities are often expressed in the terms people use. Thus the separateness of “it” and “I” is sometimes expressed by jocular personifications of the Tourette's: one Touretter I know calls his Tourette's “Toby,” another “Mr. T.” By contrast, a Tourettic possession of the self was vividly expressed by one young man in Utah, who wrote to me that he had a “Tourettized soul.”

Though Bennett is quite prepared, even eager, to think of Tourette's in neurochemical or neurophysiological termsâhe thinks in terms of chemical abnormalities, of “circuits turning on and off,” and of “primitive, normally inhibited behaviors being released”âhe also feels it as something that has come to be part of himself. For this reason (among others), he has found that he cannot tolerate haloperidol and similar drugsâthey reduce his Tourette's, assuredly but they reduce

him

as well, so that he no longer feels fully himself. “The side effects of haloperidol were dreadful,” he said. “I was intensely restless, I couldn't stand still, my body twisted, I shuffled like a parkinsonian. It was a huge relief to get off it. On the other hand, Prozac has been a godsend for the obsessions, the rages, though it doesn't touch the tics.” Prozac has indeed been a godsend for many Touretters, though some have found it to have no effect, and a few have had paradoxical effectsâan intensification of their agitations, obsessions, and rages.

41

Though Bennett has had tics since the age of seven or so, he did not identify what he had as Tourette's syndrome until he was thirty-seven. “When we were first married, he just called it a ânervous habit,'” Helen told me. “We used to joke about it. I'd say, âI'll quit smoking, and you quit twitching.' We thought of it as something he

could

quit if he wanted. You'd ask him, âWhy do you do it?' He'd say, âI don't know why.' He didn't seem to be self-conscious about it. Then, in 1977, when Mark was a baby, Carl heard this program, âQuirks and Quarks,' on the radio. He got all excited and hollered, âHelen, come listen! This guy's talking about what I do!' He was excited to hear that other people had it. And it was a relief to me, because I had always sensed that there was something wrong. It was good to put a label on it. He never made a thing of it, he wouldn't raise the subject, but, once we knew, we'd tell people if they asked. It's only in the last few years that he's met other people with it, or gone to meetings of the Tourette Syndrome Association.” (Tourette's syndrome, until very recently, was remarkably underdiagnosed and unknown, even to the medical profession, and most people diagnosed themselves, or were diagnosed by friends and family, after seeing or reading something about it in the media. Indeed, I know of another doctor, a surgeon in Louisiana, who was diagnosed by one of his own patients who had seen a Touretter on the Phil Donahue show. Even now, nine out of ten diagnoses are made, not by physicians, but by others who have learned about it from the media. Much of this media emphasis has been due to the efforts of the TSA, which had only thirty members in the early seventies but now has more than twenty thousand.)

Saturday morning, and I have to return to New York. “I'll fly you to Calgary if the weather's fine,” Bennett said suddenly last night. “Ever flown with a Touretter before?”

I had canoed with one,

42

I said, and driven across country with another, but flying with one . . .

“You'll enjoy it,” Bennett said. “It'll be a novel experience. I am the world's only flying Touretter-surgeon.”

When I awake, at dawn, I perceive, with mixed feelings, that the weather, though very cold, is perfect. We drive to the little airport in Branford, a veering, twitching journey that makes me nervous about the flight. “It's much easier in the air, where there's no road to keep to, and you don't have to keep your hands on the controls all the time,” Bennett says. At the airport, he parks, opens a hangar, and proudly points out his airplaneâa tiny red-and-white single-engine Cessna Cardinal. He pulls it out onto the tarmac and then checks it, rechecks it, and re-rechecks it before warming up the engine. It is near freezing on the airfield, and a north wind is blowing. I watch all the checks and rechecks with impatience but also with a sense of reassurance. If his Tourette's makes him check everything three or five times, so much the safer. I had a similar feeling of reassurance about his surgeryâthat his Tourette's, if anything, made him more meticulous, more exact, without in the least damping down his intuitiveness, his freedom.

His checking done, Bennett leaps like a trapeze artist into the plane, revs the engine while I climb in, and takes off. As we climb, the sun is rising over the Rockies to the east and floods the little cabin with a pale, golden light. We head toward nine-thousand-foot crests, and Bennett tics, flutters, reaches, taps, touches his glasses, his mustache, the top of the cockpit. Minor tics, Little League, I think, but what if he has big tics? What if he wants to twirl the plane in midair, to hop and skip with it, to do somersaults, to loop the loop? What if he has an impulse to leap out and touch the propeller? Touretters tend to be fascinated by spinning objects; I have a vision of him lunging forward, half out the window, compulsively lunging at the propeller before us. But his tics and compulsions remain very minor, and when he takes his hands off the controls the plane continues quietly. Mercifully, there is no road to keep to. If we rise or fall or veer fifty feet, what does it matter? We have the whole sky to play with.

And Bennett, though superbly skilled, a natural aviator,

is

like a child at play. Part of Tourette's, at least, is no more than thisâthe release of a playful impulse normally inhibited or lost in the rest of us. The freedom, the spaciousness, obviously delight Bennett; he has a carefree, boyish look I rarely saw on the ground. Now, rising, we fly over the first peaks, the advance guard of the Rockies; yellowing larches stream beneath us. We clear the slopes by a thousand feet or more. I wonder whether Bennett, if he were by himself, might want to clear the peaks by ten feet, by inchesâTouretters are sometimes addicted to close shaves. At ten thousand feet, we move in a corridor between peaks, mountains shining in the morning sun to our left, mountains silhouetted against it to our right. At eleven thousand feet, we can see the whole width of the Rockiesâthey are only fifty-five miles across hereâand the vast golden Alberta prairie starting to the east. Every so often Bennett's right arm flashes in front of me, his hand taps lightly on the windshield. “Sedimentary rocks, look!” He gestures through the window. “Lifted up from the sea bottom at seventy to eighty degrees.” He gazes at the steeply sloping rocks as at a friend; he is intensely at home with these mountains, this land. Snow lies on the sunless slopes of the mountains, none yet on their sunlit faces; and over to the northwest, toward Banff, we can see glaciers on the mountains. Bennett shifts, and shifts, and shifts again, trying to get his knees exactly symmetrical beneath the controls of the plane.

In Alberta nowâwe have been flying for forty minutesâthe Highwood River winds beneath us. Flying due north, we start a gentle descent toward Calgary, the last, declining slopes of the Rockies all shimmering with aspen. Now, lower, to vast fields of wheat and alfalfaâfarms, ranches, fertile prairieâbut still, everywhere, stands of golden aspen. Beyond the checkerboard of fields, the towers of Calgary rise abruptly from the flat plain.

Suddenly, the radio crackles aliveâa huge Russian air transport is coming in; the main runway, closed for maintenance, must quickly be opened up. Another massive plane, from the Zambian air force. The world's planes come to Calgary for special work and maintenance; its facilities, Bennett tells me, are some of the best in North America. In the middle of this important flurry, Bennett radios in our position and statistics (fifteen-feet-long Cardinal, with a Touretter and his neurologist) and is immediately answered, as fully and helpfully as if he were a 747. All planes, all pilots, are equal in this world. And it is a world apart, with a freemasonry of its own, its own language, codes, myths, and manners. Bennett, clearly, is part of this world and is recognized by the traffic controller and greeted cheerfully as he taxis in.

He leaps out with a startling, ticlike suddenness and celerityâI follow at a slower, “normal” paceâand starts talking with two giant young men on the tarmac, Kevin and Chuck, brothers, both fourth-generation pilots in the Rockies. They know him well. “He's just one of us,” Chuck says to me. “A regular guy. Tourette'sâwhat the hell? He's a good human being. A damn good pilot, too.”

Bennett yarns with his fellow pilots and files his flight plan for the return trip to Branford. He has to return straightaway; he is due to speak at eleven to a group of nurses, and his subject, for once, is not surgery but Tourette's. His little plane is refueled and readied for the return flight. We hug and say good-bye, and as I head for my flight to New York I turn to watch him go. Bennett walks to his plane, taxis onto the main runway, and takes off, fast, with a tailwind following. I watch him for a while, and then he is gone.

THE VISIONS OF HILDEGARD

The religious literature of all ages is replete with descriptions of “visions,” in which sublime and ineffable feelings have been accompanied by the experience of radiant luminosity (William James speaks of “photism” in this context). It is impossible to ascertain, in the vast majority of cases, whether the experience represents a hysterical or psychotic ecstasy, the effects of intoxication, or an epileptic or migrainous manifestation. A unique exception is provided in the case of Hildegard of Bingen (1098 to 1180), a nun and mystic of exceptional intellectual and literary powers, who experienced countless “visions” from earliest childhood to the close of her life, and has left exquisite accounts and figures of these in the two manuscript codices which have come down to usâ

Scivias

and

Liber divinorum operum simplicishominis.

A careful consideration of these accounts and figures leaves no room for doubt concerning their nature: they were indisputably migrainous, and they illustrate, indeed, many of the varieties of visual aura earlier discussed. Singer (1958), in the course of an extensive essay on Hildegard's visions, selects the following phenomena as most characteristic of them:

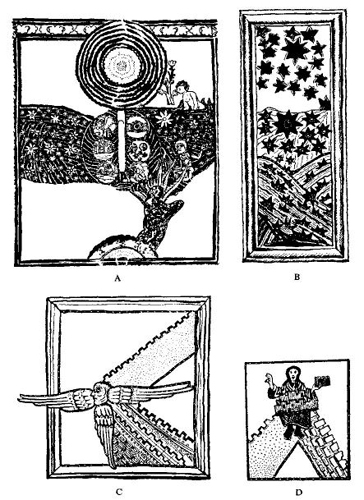

FIGURE 1.

Varieties of migraine hallucination represented

in the visions of Hildegard

Representations of migrainous visions, from a MS. of Hildegard's

Scivias

, written at Bingen about 1180. In Figure 1A, the background is formed of shimmering stars set upon wavering concentric lines. In Figure 1B a shower of brilliant stars (phosphenes) is extinguished after its passageâthe succession of positive and negative scotoma: in Figures 1C and 1D, Hildegard depicts typically migrainous fortification figures radiating from a central point, which, in the original, is brilliantly luminous and coloured (see text).

In all a prominent feature is a point or a group of points of light, which shimmer and move, usually in a wave-like manner, and are most often interpreted as stars of flaming eyes. In quite a number of cases one light, larger than the rest, exhibits a series of concentric circular figures of wavering form; and often definite fortification figures are described, radiating in some cases from a coloured area. Often the lights gave that impression of

working

, boiling or fermenting, described by so many visionaries . . .

Hildegard writes:

The visions which I saw I beheld neither in sleep, not in dreams, nor in madness, nor with my carnal eyes, nor with the ears of the flesh, nor in hidden places; but wakeful alert, and with the eyes of the spirit and the inward ears, I perceived them in open view and according to the will of God.

One such vision, illustrated by a figure of stars falling and being quenched in the ocean signifies for her “The Fall of the Angels”:

I saw a great star most splendid and beautiful, and with it an exceeding multitude of falling stars which with the star followed southwards . . . And suddenly they were all annihilated, being turned into black coals . . . and cast into the abyss so that I could see them no more.

Such is Hildegard's allegorical interpretation. Our literal interpretation would be that she experienced a shower of phosphenes in transit across the visual field, their passage being succeeded by a negative scotoma. Visions with fortification-figures are represented in her

Zelus Dei

(Figure 1C) and Sedens Lucidus (Figure 1D), the fortifications radiating from a brilliantly luminous and (in the original) shimmering and coloured point. These two visions are combined in a composite vision, and in this she interprets the fortifications as the

aedificium

of the city of God.

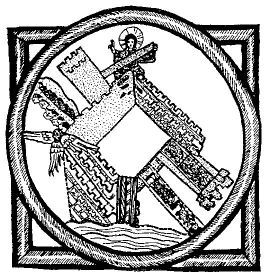

“Vision of the Heavenly City”

Great rapturous intensity invests the experience of these auras, especially on the rare occasions when a second scotoma follows in the wake of the original scintillation:

The light which I see is not located, but yet is more brilliant than the sun, nor can I examine its height, length or breadth, and I name it “the cloud of the living light.” And as sun, moon, and stars are reflected in water, so the writings, sayings, virtues and works of men shine in it before me. . . .

Sometimes I behold within this light another light which I name “the Living Light itself.” . . . And when I look upon it every sadness and pain vanishes from my memory, so that I am again as a simple maid and not as an old woman.

Invested with this sense of ecstasy, burning with profound theophorous and philosophical significance, Hildegard's visions were instrumental in directing her toward a life of holiness and mysticism. They provide a unique example of the manner in which a physiological event, banal, hateful, or meaningless to the vast majority of people, can become, in a privileged consciousness, the substrate of a supreme ecstatic inspiration. One must go to Dostoevski, who experienced on occasion ecstatic epileptic auras to which he attached momentous significance, to find an adequate historical parallel.

43