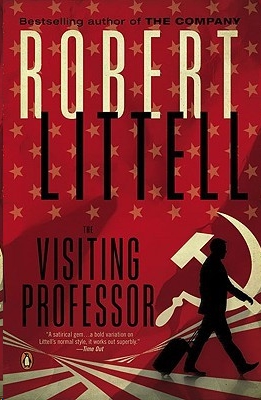

Visiting Professor

Legends

The Company

Walking Back the Cat

An Agent in Place

The Once and Future Spy

The Revolutionist

The Amateur

The Sisters

The Debriefing

Mother Russia

The October Circle

Sweet Reason

The Defection of A.J. Lewinter

This edition first published in the United States in 2006 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

Woodstock & New York

WOODSTOCK:

One Overlook Drive

Woodstock, NY 12498

[for individual orders, bulk and special sales, contact our Woodstock office]

NEW YORK:

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 100127

Copyright © 1994 Robert Littell

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-59020-906-6

F

OR

H

ENRI

B

ERESTYCKI

I

N MEMORY OF

S

UZANNE, HIS SISTER

So where is the visitin’ professor visitin’ from, huh?

And when he gets his act together, what is his act?

—Word Perkins

Order. Routine. Chaos. Joie de vivre.

—M. Ravel

Hey, I like your music. C major, wow! Rock ‘n’ roll.

—The Tender To

Lemuel Falk, a Russian theoretical chaoticist on the lam from terrestrial chaos

, threads thick, callused fingers through a tangle of ash-dirty hair that manages to look wind-whipped even in the absence

of wind. He leans his brow against an icy pane as the train spills through the marshaling yard toward the terminal; departures

he can cope with but arrivals give him indigestion, migraines, shooting pains in his solar plexus. An implausible fiction

stirs in his brain: he is the Great Headmaster, circa 1917. Long shot of a train creeping into the Finland Station. Tight

on the paramount

Homo sovieticus

, seen through a rain-stained window, worrying himself sick he will be lynched or, worse, ignored. Vladimir Ilyich’s edginess

infects Lemuel. His headache presses against the back of Lemuel’s eyeballs; his cramps pinch Lemuel’s intestines.

The fiction ebbs as Lemuel’s train docks at the quay. Shabby billboards advertising budget rental cars, mint-fresh toothpaste,

a local MSG-free Chinese restaurant, graffiti denouncing plans to establish a nuclear waste dump in the county, piles of freight

stenciled

THIS SIDE UP

drift past the window. In any given country, who gets to decide which side is up? Lemuel wonders. Under foot, there is a

hiss of hydraulics, a shriek of wheels. The train shudders to a stop. On the overhead rack, an enormous cardboard valise teeters.

Lemuel, with

improbable agility, reaches it in time and wrestles it to the floor. Outside the window, a figure Lemuel instantly identifies

as a

Homo antisovieticus

is stamping his feet to ward off frostbite. Immediately behind him, two men and two women breathe great clouds of vapor into

the night as they eye the passengers descending from the train.

Lemuel recognizes a reception committee, as opposed to a lynching party, when he sees one. Heartened, he raises a paw and

salutes them through the rain-stained window. A woman wearing fox cries, “That has got to be he,” and holds aloft a cellophane-wrapped

beacon to guide him to the Promised Land. Shrugging a worn strap of his old Red Army knapsack onto a shoulder, clutching the

cardboard valise in one hand, a duty-free shopping bag in the other, Lemuel lurches up the aisle to the vestibule, spots the

reception committee milling on the platform in a brackish pool of light cast by a naked overhead electric bulb. Struggling

with his luggage, he backs down the steel steps, turns to confront the reception committee.

The Director, tall, thin, abstemious, floating in a ski parka that makes him look lighter than air, peels off a sheepskin

mitten, cracks several knuckles and offers a cold hand. “Welcome to America,” he declares with manifest sincerity. “Welcome

to upstate New York. Welcome to the Institute for Advanced Interdisciplinary Chaos-Related Studies.” He tries to smile but

his facial muscles, frostbitten, only get as far as a smirk. His lips, which appear to be blue, barely move as he pumps Lemuel’s

hand. “I am delighted the Commie bastards finally let you out.”

“Out is where they let me,” Lemuel agrees fervently.

“To tell the truth, I never thought I’d see you on this side of the Iron Curtain.”

Lemuel mumbles something about how there is no Iron Curtain any more.

A gust of Arctic air brings tears to Lemuel’s eyes. The woman wearing fox lunges forward and thrusts six cellophane-wrapped

red roses under his nose. “Russians,” she emotionally informs the others, misreading his tears, “wear their hearts on their

sleeve.”

Until he misplaced the book, Lemuel taught himself rudimentary English from a

Royal Canadian Air Force Exercise Manual

. At a loss to see how it is possible to wear a heart on a sleeve, he pushes the bouquet back to her. “I am allegoric,” he

explains. He is desperate to make a good impression, but he is not sure how to go about it. “I break out in tears in the presence

of flowers or cold.”

The woman wearing fox and the Director avoid each other’s eyes. “Summers must be living hell for you,” the Fox remarks in

a language Lemuel takes to be Serbo-Croatian. “Winters too, come to think of it.”

The Director serves up a formal introduction. “D. J. Starbuck,” he informs Lemuel, “teaches Russian Lit 404, which is mostly

but not all Tolstoy, at the university. She is here in her capacity as chairperson of the local Soviet-American Friendship

Society.”

Lemuel, bowing awkwardly over the Fox’s hand, mumbles something about how there are no Soviets any more.

Impatience flares in D.J.’s eyes. “We are looking for a new name,” she admits in her guttural Serbo-Croatian Russian.

The Director, whose name is J. Alfred Goodacre, waves forward the committee. A man wearing windowpane-thick eyeglasses, an

astrophysicist studying cosmic arrhythmias, is introduced. “Sebastian Skarr, Lemuel Falk.” Skarr angles his head and addresses

his remarks to a distant galaxy with a mysteriously irregular pulsar throbbing in its core. “I was stunned by Falk’s insights

on entropy,” he says, almost as if Lemuel were not there. “I was mesmerized by his description of the relentless slide of

the universe toward disorder; toward chaos.”

An older man stumbles forward, removes a fore-aft astrakhan, exposing a scalp covered with a crewcut gray fuzz. “I’m Sharlie

Atwater,” he announces, slurring consonants so that Lemuel has trouble following what he says. “When I’m sober, whish is weekdays

before noon, I do surface tension of water dripping from faucets. Your paper on the relationship between deterministic chaosh

and what you call fool’s randomnesh took my breath away.”

A handsome middle-aged woman speaks up in a clipped English accent. “Matilda Birtwhistle,” she introduces herself. “I cultivate

chaos-related snowflakes in the Institute’s antediluvian laboratory. We followed your exploit with pi—calculating it out to

three billion, three hundred and thirty million decimal places. Your formulation about how if pi were truly random it would

seem at times to be ordered struck us all as incredibly elegant. None of us had given much thought to the enigma of random

order being a constituent of pure randomness.” She flashes a thin smile. “The faculty are keen to have one of the Western

world’s preeminent randomnists join the staff.”

Lemuel, roused, seizes Birtwhistle’s hand and, bobbing, brushes his chapped lips against the back of her hand-knit Tibetan

glove. The gesture is mean to convey old poverty as opposed to the newer, sweatier,

more desperate poverty of the proletarian masses. Straightening, Lemuel coughs up a nervous rasp from his throat. Dealing

with abstract ideas, he likes to think he can hold his own with an Einstein; he is less sure of himself and easily intimidated

when it comes to dealing with people. On this occasion he ducks for cover behind memorized phrases: He begs them all to presume

he is elated to have been named a visiting professor at the Institute, to believe he is eager to plunge into its chaos-related

waters.

Searching the faces of his interlocutors, Lemuel slips into a delicious fiction: The Swedish embassy has turned out to inform

him that he has been awarded the Nobel Prize for his pioneering work in pure randomness. Close in on the ambassador, wearing

sheepskin mittens. Pan to a certified bank check for three hundred and eighty thousand United States of America greenbacks

as he hands it to Lemuel. Negotiated on the Petersburg black market, that should bring roughly 380 million rubles. Set for

life, set for the next one too, Lemuel sniffs at the cold; it burns his nostrils. The pain reminds him who he is and where

he is. The members of the reception committee are staring at him as if they expect an encore. Traces of alarm appear in the

corners of Lemuel’s bloodshot eyes. His brows arch up, his nostrils flare as he departs from his prepared text, memorized

during the interminable hours of the Petersburg-Shannon-New York flight. The voyage has exhausted him, he says. He desperately

needs to urinate. Would it be imposing on their hospitality to ask for a cup of authentic American instant coffee?

Charlie Atwater, who has been holding his breath to extinguish hiccups, says, “How about shomething with a teeny-weeny bit

more alcohol content?”

Muttering “Falk badly needs a hat or a haircut,” the Fox pivots on the spiked heel of a galosh and stalks off in the direction

of the station’s coffee-vending machine. With a toss of his head, the Director invites Lemuel to follow her.

And follow her he does. With listless gratefulness, Lemuel permits himself to be sandwiched between the people who are proposing

to deliver him from a fate worse than death: chaos!

The last thing

Lemuel expected when he applied for an exit visa was to get one; the last thing he wanted was to leave Russia. It was an

un-pleasant

matter of fact that the former Soviet Union was spiraling into chaos; shelves in stores were bare, people had taken to trapping

cats and pigeons, to brewing carrot peelings because tea was too expensive, inflation was running to three-digit figures a

year, the ex-Communists who claimed to be governing in Moscow were distributing money as fast as they could print it. Lemuel’s

salary at the V. A. Steklov Institute of Mathematics, where he had worked for the past twenty-three years, had tripled in

the last four months. The price of a loaf of bread, when bread was available, had quadrupled. Pretty soon he would need a

fifty-liter plastic garbage sack (impossible to find) to bring his ex-wife her monthly alimony. Still, the chaos had the advantage

of being Lemuel’s chaos. The English scriptwriter Shakespeare had put his finger on it: Better to bear the chaos we know than

fly to another chaos we know not of. Or words to that effect.

This being the case, what prompted someone as viscerally cautious as Lemuel (he has always taken the position that two plus

two

appears to be

four) to head for allegedly warmer climes and allegedly greener pastures?

He had applied for an exit visa every year since he began working as a randomnist. It was his way of taking random samplings

of the political climate. Come September, he would fill in the appropriate forms in triplicate, stick on the appropriate government

tax stamp and drop the application into the overflowing in basket of the appropriate time-server at the Foreign Ministry’s

visa section. Every year the application would come back with a bold red “Refused” stamped across its face, proving to Lemuel

that the world he knew but did not necessarily love had the saving grace of being in order. For Lemuel, it seemed, had a working

knowledge of state secrets. Because of this, he was not permitted to stray beyond the state’s frontiers.

When, this year, a stamped, certified visa miraculously appeared in the communal mailbox, he panicked. He fitted his eyeglasses

over his eyes and read it twice, removed his glasses and cleaned them with the tip of his tie, put them back on and read it

a third time. If they were letting Lemuel Melorovich Falk—winner of the Lenin Prize for his work in the realm of pure randomness

and theoretical chaos, member of the elite Academy of Sciences—slip through their usually sticky fingers, state secrets and

all, it meant that chaos had infected the rotting core of the bureaucracy; it meant that things were worse than he had imagined.

Because they gave him permission to leave, he decided the time had come to go.

He had made the acquaintance of the Institute’s director a dozen years before at a Prague symposium on the relatively new

science of chaos. Invited to deliver a paper, Lemuel had dazzled the assembly with his work on pi, the Greek letter that represents

the transcendental number arrived at by dividing the circumference of a circle by its diameter. In his quest for pure, unadulterated

randomness, he had programmed an East German mainframe and calculated pi out to sixty-five million, three hundred and thirty-three

thousand, seven hundred and forty-four decimal places (a world record at the time) without discovering any evidence of order

in the decimal expansion of pi. The Director, impressed not only by the originality but the elegance of Lemuel’s dissertation,

had arranged for the paper to be published in the Institute’s prestigious quarterly review. One article had led to another.

Already eminent for discovering potentially pure randomness in the decimal expansion of pi, Lemuel, essentially a randomnist

who dabbled in chaology, began patrolling what he called, tongue in cheek, Falk’s Pale: the gray no-man’s-land where randomness

and chaos overlap. Every time someone put forward a candidate for pure, unadulterated randomness, he would subject it to the

rigorous techniques of chaology, then advance proof that what looked like randomness was in fact determined albeit unpredictable,

and therefore not pure randomness at all. Nature, according to Lemuel, generated complexities so vast, so unpredictable, that

they appeared to the naked eye to be examples of pure randomness. But this “fool’s randomness,” so he argued in a paper that

gilded his reputation in America, was nothing more than the name we gave to our ignorance. We did not know enough. Our instruments

were not sensitive enough. Our sampling was not spread over a long enough period—something on the order of a million years.

Once you burrowed under the surface—once you perfected the instruments with which you measured randomness, once you increased

the period over which the measurements were taken—you discovered (to Lemuel’s bitter disappointment) that what passed for

pure randomness was not random at all, but a footprint of what physicists and mathematicians had taken to calling chaos.