Walking with Abel (2 page)

Authors: Anna Badkhen

—

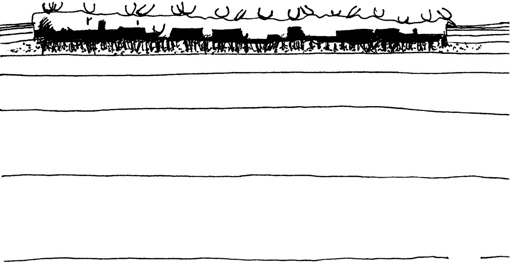

Oumarou’s dry-season grazing grounds lay in the fecund seasonal swamplands in the crook of the Niger’s bend, in central Mali. The Fulani called the region the bourgou. Bourgou was hippo grass,

Echinochloa stagnina

, the sweet perennial semiaquatic species of barnyard grass that grew on the plains from late summer till winter’s end, when the anastomosing stream of the Bani River flooded the Inner Niger Delta. Hippo grass shot its spongy blades up to nine feet out of the wetlands. Its rhizomes floated. It was a drifter, like the Fulani. Cows went wild for it.

The Diakayatés had arrived in the bourgou in January, after the rice harvest. Oumarou and his sons and nephews and grandnephews had raised their domed grass huts in a slightly swerving line of six beneath a few contorted thorn trees on a strip of dry land that bulged out of a fen so deep that the cows had to swim to return to camp from pasture. The thorn trees had fingered the soft wind of early winter with feathery peagreen leaves.

By July the island was a cowtrodden knuckle barely manifest on an enormous spent plateau. The fen was a foul sike, fragmented and not ankle-deep. All about, the oldest continental crust in the world lay bare, its brittle rusted skin ground to red talc by cattle and the dry harmattan winds of February and the cruel spring heat. The three thorn trees that flanked Oumarou’s hut had no more leaves, and in the dusty naked branches agama lizards with orange heads rotated their eyes and pressed up and up in a laborious Triassic mating dance. To the northeast, the millet fields of slash-and-burn farmers smoked white against dark gray rainclouds that refused to break. The rain was late.

Oumarou had not heard the planetary-scale metastory of the most recent global warming. He had not heard much about the planet at all. He had not even heard about Africa. He could not read, did not listen to the radio. He took bearings by other coordinates calibrated in other ways, brought into existence billions of years before the Earth itself. He sought counsel from the stars.

For centuries the Fulani had aligned the annual movement of their livestock from rainy-season to dry-season pasture and back again with the orderly procession across the sky of twenty-six sequential constellations. Each signified the advent of a windy season, of weeks of drizzle or days of downpour, of merciless heat or relentless malarial mosquitoes that danced in humid nights. But for decades now the weather had been chaotic, out of whack with the stars. The rainy season had been starting early or late or not arriving at all. Oumarou was searching for the promise of rain conveyed across millions of light-years, and he could not reconcile the cycle.

In this part of the Sahel, the first week of June was the brief season the Fulani called the Hoping, when people looked at the sky expecting rain any day. This year the Hoping had stretched into two excruciating weeks, then three, then four. Oumarou’s cows hung deflated humps to the side and let down little milk. Milk made up most of the old man’s diet. He was nauseous with hunger.

“Three things make a man live a long and healthy life,” he would repeat over a succession of disappointing dinners of bland millet-flour porridge with sauce of pounded fish bones. “Milk, honey, and the meat of a cow that has never been sick.” Honey was a rare treat in the bush. As for beef, that was a conjecture, a hypothesis. The Fulani very seldom ate meat, and when they did, it usually was goat or lamb. No Fulani would readily slaughter a healthy cow.

—

Oumarou freed an arm from his blanket and paced off the sky to the sun with a narrow hand. Half a palm’s width. A flock of birds burst out of a low shrub, chirped, circled, settled again. The uninterrupted horizon quivered with birdsong, lizards’ click-tongue, the whimper of goats, the hoof-falls and lowing of moving cows. Eternal sounds. Ephemeral sounds. Three more fingers and the cows would be gone. Time to pack.

Oumarou looked at Fanta, his wife, his fellow rambler, who now stood by his side listening to the faraway herds also.

“Ready?” he said.

O

umarou’s restlessness dated back to the Neolithic, to the time when a man first took a cow out to graze.

It was an outsize brown cow that stood six feet front hoof to shoulder and bore a pair of forward-pointing, inward-curved horns such as the ones that eventually would gore tigers and bears in the coliseums of Rome. The last of her undomesticated tribe, a female wild aurochs, would die of disease or old age or hunger or loneliness in the Jaktorów forest in Poland in 1627. Around 10,000

BC,

ancient humans began to encourage the

Bos primigenius

to stay close. How? Maybe they used salt to entice the massive ruminants, as people did in the twenty-first century with the wild mithans of the Assam hills, with northern reindeer. Or maybe, like the Diakayatés did on cattle drives, they simply sweet-talked the aurochs into sticking around. “

Ay

,

ay

, girl!” One way or another, sometime in the early Holocene a colossal proto-cow felt trusting enough around people that she allowed herself to be milked. Milking would become like walking: essential, innate. It was why God gave man opposable thumbs.

In Africa, herders preceded farmers by some three thousand years. In Asia, pastoralism evolved after agriculture. Anthropologists disagree whether people domesticated cattle on these two continents independently or whether itinerant Asian traders brought the cow to Africa, though DNA studies indicate that all taurine cattle came from eighty female wild aurochs. In any event, during the Agricultural Revolution, Cain and Abel parted ways, and from then on, “the nomadic alternative,” as the writer-wanderer Bruce Chatwin called it, developed parallel to, and in symbiosis with, the settled culture.

Antecedent herders grazed their kine in the lush pastures of East Africa. Around 8000

BC

, people at Nabta Playa, an interglacial oasis in the Nubian Desert, littered their primeval hearths with pottery and bones of ovicaprids and cattle. Ten thousand years from now, archaeologists of the future will scrape the same refuse from the midden of Oumarou’s campsite—cow bone and goat crania and cracked bowls, plus some empty glass vials of commercially manufactured vermicide.

Around 6000

BC

, some bands of nomads hit the road. Perhaps, as sedentary farmers carved pasturage into millet and sorghum fields, they had run out of country. They drove before them lyre-horned zebu cows: much smaller than the wild aurochs, requiring little water, able to withstand high temperatures, docile, and partially resistant to rinderpest. The herders were tolerant to lactose and lived mostly on milk. Their limbs were stretched by protein. Their bones were strong enough to chase clouds. Like Hollywood cowboys, they hooved it west.

Today the unlettered Fulani in the bourgou without effort can trace the beginning of their passage to the very birthplace of mankind. I don’t know how they know. Western anthropologists, linguists, and ethnographers have puzzled over Fulani origins for more than a hundred years, measuring skulls, divining cadences of language. But ask a cowherd in Mali where his people came from, and he will reply: “Ethiopia.”

—

The nomads marched their cattle through a Neolithic Sahara. The land was lush, sodden with the subpluvial that had followed the last glaciation. Herds of hippopotamus and giraffe and ostrich and zebra grazed along mighty rivers. The rivers were full of fish. You can still see their dry courses from space.

Around 4000

BC

they stopped at the Paleozoic obelisk forest of Tassili n’Ajjer, the Plateau of the Rivers, a migrants’ oasis in what today is Algeria. There, on sandstone, the nomads painted and engraved Bovidian odes to cattle. Herds on the run. At pasture. Humped. Unhumped. Longhorned. Piebald. One painting shows a person milking a cow as a calf stands by, probably to encourage the cow to let down her milk. Someone picked into a rock a cow weeping rock tears. What was the artist’s dolor? The beautiful stones of Tassili are silent.

By 2000

BC

a great drought had returned. The desert—in Arabic

sahra

, the Sahara—pushed the herders south. Perhaps for the first time these land-use innovators had to adapt to climate change. They hooked down toward the westernmost edge of the region that Arab traders and conquerors later would call

sahel

, the shore: the savannah belt that stretches from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, linking the Sahara and the tropics roughly along the thirteenth parallel.

Trapped between the lethal tsetse forests of the south and the northern desert, Fulani cattle herders ambulated the semiarid grasslands of western Sahel. They plodded toward the Atlantic, into the coastal reaches of modern-day Senegal, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana. But just south of the town walls of modern Djenné, less than a day’s walk from the Diakayatés’ dry-season camp, one of the oldest known urban centers in sub-Saharan Africa, Djenné-Djenno, pokes its ruins out of the earth. Excavations at Djenné-Djenno have revealed bones of domesticated cattle and goats and sheep that date back to the beginning of the first millennium

AD

. Oumarou’s forefathers may have passed through already then.

The Fulani thrust inland in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Many of them were Muslim. “Generally of a tolerant disposition,” the Nigerian scholar Akin L. Mabogunje wrote in his essay “The Land and Peoples of West Africa,” the Fulani were embraced “for the manure their cattle provided on the fields and for the milk and butter which could be exchanged for agricultural products.” That arrangement never has changed. When I met them, the Diakayatés lived on the millet and rice and fish Oumarou’s wife, Fanta, swapped for butter and buttermilk, and villagers welcomed his cow dung on their fields as long as it was not at the time of planting, during the rainy season, or at the time of harvest, right after. As the Fulani had been doing for thousands of years, the family notched and notched the routes of ancient transhumance deeper into the continent’s bone, driven by a neverending quest for pasturage, a near worship of cattle, and the belief that God created the Earth, all of it, for the cows.

In the early nineteenth century, a Fulani scholar, cleric, and trilingual poet named Uthman dan Fodio launched one of West Africa’s earliest jihads. Hurtling camelback and horseback, dan Fodio and his followers delivered Sufi Islam to the mostly animist rural savannah on the tips of their spears and broadswords. In the floodplains of the Inner Niger Delta, one of dan Fodio’s disciples, a Fulani orphan named Ahmad bin Muhammad Boubou bin Abi Bakr bin Sa’id al Fulani Lobbo, led an Islamic uprising and created the theocratic empire of Massina. Twenty-first-century Fulani remember and revere him by his preacher sobriquet, Sekou Amadou: Sheikh Muhammad.

Sekou Amadou made his first capital at the village of Senossa, a sparse oasis of low adobes and doum palms above a swale that separates the village from Djenné. Then he set out to purify what he saw as his subjects’ corrupt mores. He banned tobacco and alcohol, established purdah, set up social welfare for widows and orphans, and regularized land use, drawing up seasonal timetables that distributed pastures and rivers among Bozo fishermen, Songhai traders, Mandinka and Bambara farmers, and Fulani herders. He favored the cattlemen; the nomads thrived. Almost two hundred years later the amplitudes of Oumarou’s migration still abided by the transhumance schedules Sekou Amadou had drawn in 1818.

—

By the beginning of the twenty-first century an estimated thirty to forty million nomads roved the world, herding cattle, deer, goats, sheep, yak, camel, horses. Some twenty million of them were Fulani. Their ruinously swelling herds, confined by state borders, frontlines, and megalopolises that were recharting the Sahel, competed with expanding farmsteads for depleted and dwindling resources. Demographers in the West predicted that the next big extinction would be theirs. That in a hundred years, we all would be settled, and living in cities.

When I relayed this to Oumarou he was distressed. For more than seventy years, since the first year he could remember, he had spent the dry season on the narrow island right here, in the middle of the sweetgrass marsh an hour’s walk northwest of Senossa.