Walking with Abel (26 page)

Authors: Anna Badkhen

A

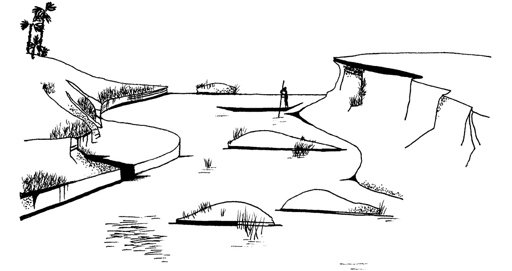

mile or so east of Ballé the dry land suddenly swept toward the Bani River in a grassy slope where Allaye and Sita were already waiting with the goats. The river was bluegreen. It carried goat droppings, shreds of torn nets, bits of tackle, faint petroleum rainbows. It carried Djenné’s sewage and brocade dyers’ lye. It carried love songs of laundresses and all the desires and regrets that drained into a watershed three times the size of the Hudson’s. From its headwaters in Côte d’Ivoire to the bourgou in central Mali it seamed and sundered the Sahel with oxbows and veins and here, at Ballé, near the end of the six hundred and eighty miles of its meanders toward the Niger, it seamed and sundered the Diakayatés’ migration with biannual crossings.

The river was the egress and the access. It divided the year into two seasonal pasturages: the rainy, when it was the gateway to the time of hope, and the dry, when, on a good year, it ushered the Fulani and their cattle into at least a few weeks of sated rest. It sloped its west bank toward the bourgou into which it spilled in late summer months, flooding rice paddies and irrigation canals and swales and sometimes entire villages built carelessly low, and it thrust its east bank up toward the sun. Although it was not very long, the Bani was wide and, during the rainy season, deep and murderously fast, a force to venerate and heed. Twice yearly, in the early days of rain and at the onset of the cold months of winter, the east bank became the point of convergence of dozens of Fulani families on the move, a place of assembly and parting, a staging point for a seasonal mass migration. It was fitting to pause before crossing such a boundary.

The Diakayatés unhitched the carts and right away the donkeys wandered off to graze on tiny daisies. Unmanned pirogues lolled in the shallows. Oumarou sat looking across the water at the east bank, where last rays bronzed a swallow-hollowed sandstone cliff. On that cliff, at the very crest that caught the first light of morning and held on the longest to the last light of the day, Oumarou had buried his father, a daughter, and a son in a small wood of doum palms. On the plateau beyond the graves was his youngest son, Hassan, and his cattle, and his brother al Hajj Saadou. Oumarou would cross the river in the morning and the reunion would be sweet. The nomads were always leaving, leaving—and they also were always returning, returning.

The land let go of the light at last. Everyone was dog-tired. The men pulled down some matting from the carts and lay upon it. Ousman cradled baby Afo and brewed tea. Bobo mixed handfuls of

chobbal

with river water. We drank.

I

wanted to see the world. I walked from Hayré with a friend to the big asphalt road and I took a bus and went to Bamako. I’d heard about Bamako and wanted to see it.

“When I got to Bamako I just spent two nights there. I liked everything. Such a good city! Nice houses, nice clothes, nice people, nice cars, electricity everywhere. I stayed at my friend’s relatives’ place—I don’t know the name of their neighborhood. A nice neighborhood.

“While I was there I heard that I could prospect for gold in Côte d’Ivoire. So my friend and I went there. We took buses, with several layovers. At the gold mine we spoke Fulfulde, Bambara, and Mossi, the language they speak in Burkina, because the owner of the gold mine was from Burkina. We would start at eight in the morning and stop at noon. If we worked for two days in a row we were paid fifty thousand West African francs for two days of work. It was easy. The owner had this machine that took out the mud. Then we took that mud to another machine that pounded and washed, and then we used mercury to separate the gold. When you find a kilo of gold you get twenty million West African francs. I never found a kilo of gold, though.

“I spent one month at the mine. Then I traveled around Côte d’Ivoire because I wanted to see the country. I took little jobs in Abidjan. I ran errands for shop owners. Just small-time retail: clothes, shoes, electronics. I pushed carts with boxes and helped around the shops.

“If I had to choose between the bush and Bamako I’d choose Bamako. I’d move there if my parents agreed. I really like to travel and I’d like to travel to the United States.”

Allaye’s heavy rings shone dull orange in the orange flickers of the brazier. A slender boy with smooth skin. His identity card said he was twenty-one. He spoke in a half-whisper, so that only Gano and I could hear. He said he had brought from his seven-month sojourn five hundred thousand West African francs: more than a thousand dollars. With that money he could either marry and buy a few cows or buy a house. But he wanted to do both, and he also wanted to hire cowboys to herd his cattle so he could enjoy the pleasures of his wife and of life in a city, and so he was planning to return to Abidjan to earn more money.

“Anna Bâ, next time you go to Bamako, take me with you.”

“Don’t they need your help here now, during the rainy season?”

“They have three people, they don’t need me. That’s plenty of hands. I want to earn money. The fifty thousand I earned in Côte d’Ivoire—I’ve spent nothing of it. I’m saving up for a beautiful life—oops, excuse me!” Allaye spotted his father’s and uncle’s goats trot west toward Ballé, and he jumped up and dashed into the night in bare feet after the animals to steer them back toward the river.

“Ay!

Ay, shht!”

Allaye had not told his father about his plans, or about the money he had brought. Oumarou had not asked. “I’m studying him,” he would say. “I’m waiting.” From his mat he watched his son’s dancing figure chase the scattering goats and spoke clearly and gravely.

“When Allaye returned last week I saw that he hasn’t changed very much. He is still the same Allaye. He’s just changed in his body, became a little less weathered. His color became the color of someone who lives in the city. He has a cellphone that makes and receives calls. I have forgiven him. I’m happy to see my son back. I hope he becomes successful. But I will not accept that my sons live in the city. In the city there is nothing for the cows to eat, no place for them. I want my sons to always herd cows. Cows can give milk. If these children who eat money are so hellbent on getting money, they should know that milk can be used for a lot of things, even for money.”

The old man stabbed the dark with his long index finger, pinning his sons forever to life on the hoof. A Pel’s fishing owl flew out of the west and disappeared over the water.

—

Late at night the Diakayatés quietly walked to the Bani to wash. They took turns, mindful of one another’s privacy. I went last. The water was warm and silty. A strong and soundless current tipped away from a skyful of stars. Darkness deepened the silence.

A

bove the slope where Oumarou’s family made camp that night there stood a coppice of mangoes and doum palms that concealed almost entirely from view a couple of banco huts. The grove and the huts belonged to the extended Bozo family of Kotimi Genepo. The Diakayatés had relied on the Genepos to help them cross the Bani during migration since before Oumarou was born. Back then the Bozo family, too, had been nomadic, moving along the river in boats and stopping from time to time long enough to raise cylindrical cane dwellings on its shores. The Genepos had settled in the grove in the nineteen eighties.

The men poled their pirogues up and down the waterway, one quiet man per boat. They wove and patched their nets and sometimes they tilled with a four-ox plough a small patch of swampland that lay behind their huts. They kept a small flock of goats that fed on refuse and riverside grass. The women, whom Bozo taboos forbade to fish from boats, set fishtraps in the point bar, raised chickens and guinea hens, and traveled to markets in Djenné and Madiama, a large village between Ballé and Hayré, to trade fish and doum nuts and mangoes and peanuts, depending on the season.

Like everyone else in the bush the Genepos fixed their life to the progression of stars. Stars announced the arrival of the blue-tinged Nile perch, of the short-striped daggers of clown killi, of the lunar disks of the Niger stingray. The river was never the same and yet it was, and the fishermen relied on the predictability of each day’s haul: the thickheaded catfish for smoking and stewing, the tiny petrocephalus and oily raiamas for deep-frying, the scaly flanks of African carp, a shimmering mess of minnows. But, like the savannah around it, the river was behaving strangely. The droughts that throttled the land were wringing it dry. Flash floods washed away harvests and entire homesteads, altered the relief of the banks and the bottom. Acres of deforested riverbank dried out and blew away. The abrading topsoil no longer kept alluvial cutbanks from slumping into the water. And now big-town markets sold imported, ready-made fishing nets, which Bambara and Dogon farmers and Songhai traders who never before had waded into the water now used to trawl the river, taking what the Bozo believed belonged only to them.

It had drizzled on and off all night, and a thin moon shone sickly through the clouds. At last, a sunrise broke through thunderclouds. To the north stretched a black sky, and on the horizon hung the pink glow of lightning. The cloudline ran over the camp exactly, dividing the heavens in two. The river sparkled with dawn. But within an hour the sun had gone behind black clouds, and the river, too, had turned black.

Gano and Allaye and I walked into the grove to buy some fresh fish for breakfast. But Kotimi just smiled.

“I have very little, and I don’t think you’d want it.” She peeled back the black tarp over her smoker and looked down at a few handfuls of tiny smoked carp, each no larger than a thumb. She smiled again, as if apologizing for such paucity. The Bani was spent.

Kotimi handed us several doum palm nuts: Bobo and Hairatou would scorch their fibrous and fermenting yellow meat to black strands over the cooking fire and that would be our breakfast. Then she walked us down to the water and waded in. A few steps from the shore she bent down to drown a woven fishtrap, fixing it in place with a fist-size rock. Maybe a catfish would wend its way inside. Without unbending she washed her face, rinsed her mouth, spat a long spurt of water back into the stream. She straightened out. She smiled again. She walked home, up the slope. A ghostly light shone upon the slate river.

Once Kotimi had showed me a cherished souvenir, an aluminum ring with an etching that read: “Inform

RIKSMUSEUM STOCKHOLM SWEDEN

.” And a number: 9247797. A bird ring.

“It came to the river when this one”—she pointed at a teenage boy—“had just stopped nursing. We’d never seen a bird like that. It was diving and flying. It was white and had a big beak.”

“We have birds, but we never put rings on our birds. Who does such a thing?” Kotimi’s uncle said.

“What happened to it?”

“We killed it and threw it on the grill.”

“Oh my God was it tasty!”

“I’d never tasted any meat so sweet in my life.”

The boy did not remember the taste of that bird. He had been too young. But he nodded at his mother, and grinned. He had been hearing stories of that legendary feast his entire life. He was wearing a black t-shirt with a stenciled drawing by the American graffiti artist Shepard Fairey. Below the drawing was the word

OBEY

.