Wanderlove (25 page)

Authors: Kirsten Hubbard

Tags: #Caribbean & Latin America, #Social Issues, #Love & Romance, #Love, #Central America, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Art & Architecture, #Family & Relationships, #Dating & Sex, #Artists, #People & Places, #Latin America, #Travel, #History

Externally, it’s obvious. My sunburn turns to tan. My wind-thrashed hair is almost untamable, even by Rowan’s rolled-up bandanas. Bug bites materialize on my legs, though I never catch a single mosquito sucking at me. When I show Rowan, he tells me about other Central American beasts that bite. “Sea lice. Sand flies and fleas. Sea serpents.”

“I call bullshit on your serpents.”

“There really are sea snakes, though.”

As if I needed another reason to stay out of the ocean.

Biking barefoot with my sandals in the basket, I fly down Front Street. I dodge potholes on Middle Street. Clutching an iced papaya drink in one hand, I sail down Back Street. I wave at everyone I pass—locals, backpackers, guys and girls and children—but I’m speeding way too fast for conversation.

I stop only to draw.

Until now, I’ve been pecking at my sketchbooks, erasing, sketching with painstaking care, perfecting every line. Like every single page I drew was designed to impress my invisible critics. Well, one critic in particular. But on this island,

I don’t care what he thinks. I have really, truly left him behind.

I draw pelicans, frigate birds, grackles, gulls, herons.

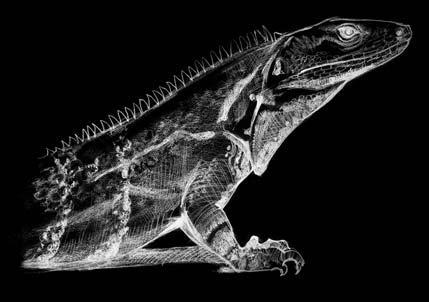

I draw iguanas, weathered old dinosaurs basking in the sun.

I draw island dogs.

I draw island kids.

I sit on a tombstone, which I hope isn’t disrespectful, and draw the island’s tiny graveyard. I draw the briar patches of the mangroves, trees that grow right out of the sea. I draw the ice cream shack when I’m craving a second scoop but too embarrassed to go get one. I draw until I fill my sketchbook and have to buy a third.

I’m so happy I can barely stand it.

But my happiness comes with one major stumbling block: it makes me even more aware of how little time I have left.

My plane leaves from Guatemala City four days after Lobsterfest. College is supposed to start a month after that. I’ve been so busy I haven’t thought about it in days.

Once I remember, time starts rushing by even faster, so fast I can see the minutes zipping around me like one of those cartoon time warps. I feel unhinged, propelled forward, as if the wind’s bashing me in the face even when I’m off my bike, and time’s flying, I’m flying, and real life and the college I don’t want are speeding toward me like the front bumper of a semi truck.

The only thing that anchors me is Rowan.

Every afternoon, I wait at the dock for the dive boats to come in.

First there’s Devon and Clement’s boat, for certified divers exploring the deeper, farther places, like the legendary Blue Hole, which I picture as a bottomless pit filled with thousand-tentacled creatures baring fangs bigger than Belize City lighthouses. Jack climbs off the second boat first, with a stack of weight belts slung around his neck and a dive tank in each hand. He always has something smart-assed to say to me. Like

“Hungover, as usual. Didn’t I warn you to stop at number nine?” Or “It’s because you’re bite-sized, isn’t it? Good thing—those hammerheads looked hungry today.” I’ve been avoiding him as much as possible, because the sight of him makes me wonder about things I don’t want to wonder about.

Next come the dreadlock twins. Emily and Ariel follow, bickering loudly.

Rowan always emerges last, looking like some sort of pony tailed mer-creature in his unzipped wet suit. He grins boyishly and says, “Don’t listen to Jack. Next time, you should come along.”

And I shake my head and grab an armful of flippers before following him to shore.

In the evenings, Emily and Ariel act like puppies, jostling for Rowan’s attention. He’s civil—at least, he doesn’t play any of his notorious pranks—but it’s obvious he prefers my company.

Just not in

that

way.

It’s a relief, really, that we established our relationship once and for all, that night we shared the hammock. The murkiness has been clarified, the tension dispersed. At last, there’s an easy peace between us.

We find the time to talk before dinner, or after we excuse ourselves from the group at night. Before long, everyone knows those hours are ours, even Rowan’s fan club.

Rowan’s sixth travel rule:

Downtime is the best time.

Rowan admits that one day, he’d like to write books.

There’s no shame, he claims, in being a Flashpacker: a backpacker with a laptop and other techno-toys. I describe my histories with Reese and Olivia, the way I drifted from one to the other, then away from both. And I talk about how I used to love to swim at one particular beach, my beach, a long time ago but not anymore, even though I don’t tell him why.

Rowan tells me about the dad he shares with Starling: a failed architect turned landscaper, terminally unhappy, always on the move to escape a boss, a woman, or another imaginary enemy. He doesn’t talk about his mother, and I don’t ask.

I tell him about the art school girl, and even my art school dreams. But I don’t tell him my reasons for discarding them, and he doesn’t ask.

Little sacrifices to keep us content. To convince us we’re making progress.

And maybe we are. It’s like carving a sculpture from a hunk of marble. Exposing the artwork hiding inside, chip by chip. But the process is slow. Too slow, when our trip is already winding down. Which I don’t want to think about.

One time, Rowan asks if I’ll ever draw him. We’re sitting on the beach, atop an overturned rowboat. I shake my head.

“It’s just too . . . intimate.”

“Really? But don’t you draw, like, models? Strangers?”

“It’s different then. When I’m drawing a stranger, it’s easy to break them down into lines, shapes, edges. Forgetting the person isn’t a problem, because you don’t

know

the person.

That’s how I can draw an old man’s . . . you know, and not be embarrassed. And also, models rarely ever see the drawing—there’s no pressure to achieve a likeness they’re happy with.

But friends are different.”

“I wouldn’t care if your drawing didn’t look like me.”

“You

say

that.” I roll my eyes. “Drawings are interpretations, right? By definition. But when I draw a friend, I can’t just interpret

clinically

: I see them through a veil of what I know, what I feel. That’s what I mean about the intimacy.

About how it’s personal, for both of us. So the process is already different. But the product is what really stops me.” I think of the time I drew Olivia. She claimed she really liked it . . .

except

.

“When people are faced with their flaws—and my artistic limitations—they’re never as happy as I need them to be. I know it’s dumb that I need validation. If I ever wanted to be a professional, I’d have to swallow all that to earn a paycheck.

But for now, I can’t help it. It’s too important to me.” When Rowan doesn’t say anything, I glance at him.

“What?”

“Nothing. I just love to hear you talk about art.” He pauses as a pelican dives into the water right in front of us. A piece of my chest seems to plunge with it. “Do you think you’ll ever show me your drawings?”

The pelican surfaces, a fish flopping in its enormous beak.

“Soon,” I promise. “Will you ever tell me about your sordid past?”

Rowan laughs and shakes his head. “Soon.” Although we’re both all too aware our time is running out.

When you spend days aboard a rickety beach bike and there are potholes all over the place, it’s basic probability: you’re destined to take a spill. Lucky for me, my wipeout occurs on the south side of the island, and my audience is mostly birds and lizards.

Mostly. Because when I finish cursing and totter to my feet, I discover I’ve fallen in someone’s yard. A woman stands nearby with a spatula in her hand, like she’s about to smack me. She’s even shorter than I am, with an enormous bosom that tapers to skinny legs and tiny feet. She wears a wrinkled Sesame Street T-shirt, with Elmo and Grover beaming freakishly across her chest.

“What you looking at, girl?”

“Oh, n-nothing,” I stammer. “I—”

“Well, what you waiting for? These

plátanos

is getting cold.”

I gape at her, trying to figure out what the heck a

plátano

is.

The woman mutters something in Kriol. “Quit yawning at me. Are you a baby bird or a girl? You can call me Sonia.”

“I’m Bria.” Finally, I leave my bike on its side and perch tentatively on a picnic bench. I’m not really sure what’s going on, but she seems friendly. Like a wolf wagging its tail. Despite her tiny feet, she moves quickly, zipping between the grill and the table, loading two plates with a Belizean breakfast of refried beans, tortillas, scrambled eggs, and fried plantains, which are probably what she meant by

plátanos

. She sits across from me and shoves a plate my way. “Really? You don’t mind?” I say.

“Mind what? You joining me this breakfast? I should thank you.” She rolls a tortilla into a shovel shape and scoops a heap of beans. “Morning’s boring as shit. My husband, he fishes dawn till dusk.”

“What does he fish for?”

“Fish. Conchs.” She pronounces it

conks.

“But now is lobster season, so he fishes for lobsters. You going to the lobster party?”

“Sure—how could I not?” It’s all anybody talks about, with the exception of Rowan.

“So you’re a backpacker?”

I shrug. “I have a backpack, at least.”

“I was a backpacker too,” Sonia says. “Girl, don’t look so surprised! We got travelers

from

here as well as

come

here.” She spoons a giant pile of sugar into her coffee and stirs. “So you like my island?”

“I love your island.”

She chuckles. “If you love it now, you should see it before.

Back before there’s more hotels and bars than shells. Back when only real backpackers come and visit. You’re too skinny,” she adds. “Eat more eggs.”

I take a bite. “What do you mean?”

“Eggs give you big tits.”

“No! About the real backpackers.”

“Oh. Well, it’s thirty years ago or more. You know La Mariposa? By the main dock?”

“Sure,” I say. The hotel with the butterfly paintings. By now, I know where everything is. I could draw an entire map out of my head. Maybe I should.

“La Mariposa is my sister’s hotel. But she’s a

bruja

and we don’t talk no more. Anyways, the whole southern part of the island, from the channel to the main dock, is mangrove forests thirty years ago. Now there’s a thousand people live on this island. Then, there’s just three or four hundred.

“In those days, only the

real

backpackers visit. Those carrying real backpacks—not these giant monster bags, look like a turtle house. There’s no water taxis, no airstrip. To get to my island, you have to pay a fisherman in Belize City to take you on his boat. Maybe if you’re lucky, he put you up in his house.

Or you find two coconut trees and put up a

hamaca,

and hope no coconuts falls on your head in the night.”

“What did people eat?” I ask, imagining

Survivor

-type hippies scavenging for shrimp and mangos.

“They eat what everybody eats,” Sonia says. “You pay a family in the morning, and in the evening, you have what they have—stew chicken, fried fish,

pollo a la plancha

.” I wonder if Rowan’s ever traveled like that. It’s easy to picture him hailing a fisherman, stringing up a hammock. I remember the island he told me about—the one with all the stars. And suddenly, I want to see it so badly my stomach aches. I want to string up a hammock under the stars and eat

pollo a la plancha.

I don’t ever want to go home. “It sounds amazing.”