Warrior Pose (11 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

Dennis whispers, “This is trouble.” I'm about to agree when Nkunika bursts back into the car, shoving the young men aside, slams the door and rolls down his window still yelling that he fought against racism before they were born. One of the battered trucks is pushed back and we roar through the roadblock. Dennis and I look at one another and sigh in unison. Without Nkunika, who knows what would have happened.

“These young men are crazy,” Nkunika says at a jungle hut where we are spending the night. “They don't know anything about this struggle. They are filled with rage. All they want to do is rob people.”

We are having a simple dinner of

nshima

, a bland, pasty dish made from maize. It's also called mealie-meal. It's almost impossible to swallow. Then it sticks to your ribs.

“It's hard to blame them,” I say. “They've been terribly oppressed. There are no jobs, no future. I understand why they would want to rob us. What did you say that saved us?”

Nkunika smiles. “I lied to them,” he answers. “I told them we had three more trucks behind us in an armed convoy and they would all be killed on the spot if they didn't let us go and scram before our soldiers arrive.”

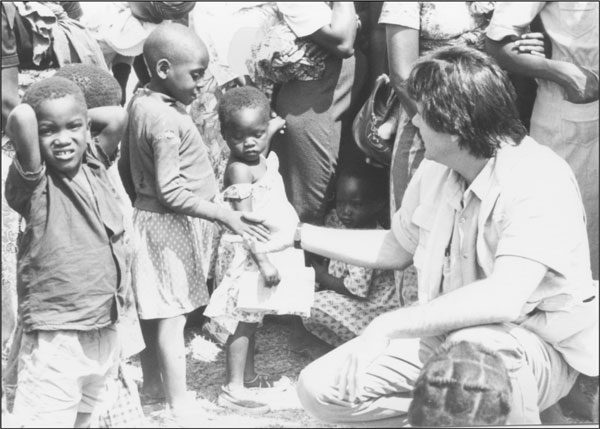

The following morning, deep in the arid bush, we film lines of women standing for hours in the brutal sun with their children to get a few cups of grain from humanitarian organizations. Relief workers weigh their infants and provide powders for malnutrition, diarrhea, and dehydration. Despite the obvious poverty, many of the children seem happy and are glad to see us there. Others stand with blank gazes, flies covering their faces, lips bleeding from the scorching heat, bellies swollen like ripe watermelons from the ravages of dysentery.

Zambian countryside, 1986.

In preparing for this trip, I came across facts that floored me: Half the people in the world live on less than two dollars a day. More than thirty thousand die daily from starvation; of these, fifteen thousand are children. We came to do a story on apartheid in South Africa and Nelson's movement, but we've also captured scene after scene of the poverty that rules these African nations, and I will weave it into the narratives at every opportunity.

Thinking about this on the flight back to Boston, I realize I take so many simple luxuries for granted: A beautiful home. A refrigerator filled with so much food there's always some that's going bad. A bathroom with running water. More widgets and gadgets than anyone needs. It's embarrassing. What are any of my problems compared to those who are forced to struggle every day just to survive? Who am I to ever complain about a sore back, even if it's on fire right now as I sit in first class having a filet mignon and my second glass of cabernet?

CHAPTER 6

Drug Wars

T

HE YEAR 1989 is coming to a close, and crack cocaine is exploding on the scene. Crack is a highly addictive form of the drug that is smoked for an instant high. Its name comes from the crackling sound it makes when it's lit. It's cheap and readily available on street corners, and many inner-city Boston neighborhoods are ruled by gangs, guns, and drugs. It's a powerful story, and it's complicated. Gangbangers are building empires, and there are shootouts in the darkest hours of night. Innocent victims get wounded and sometimes killed. Courageous cops risk their lives. Corrupt cops are on the take. Weapons flood the streets. This is much more than a local story. It's a national epidemic. An estimated 2 million Americans use cocaine. More than a quarter of a million are already hooked on crack.

Hoping to turn off the tap at the source, President George H. Bush is holding a drug summit in Cartagena, Colombia, with the leaders of Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru, where most of the world's cocaine is produced. Cartagena is a magnificent, centuries-old city sitting on the confluence of the Magdalena River and Caribbean Sea. I took working vacations there a few times before moving to Boston, helping produce an International Music Festival for Colombian TV with Camillo Pombo, the nephew of Colombian president Cesar Gaviria. It's a natural. I've got a strong local angle on a national and international story, and I have good connections and know my way around where the summit is being held.

When I pitch the story, news director Stan Hopkins supports me again, and I'm soon in Cartagena with Dennis, broadcasting live reports from a temporary headquarters set up by NBC's Miami Bureau. The summit is big news around the globe and all the networks are here, along with Latin, European, and Asian correspondents. But it's more political theater than substance. The United States blames the source countries and wants the coca crops destroyed. Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru resent being blamed. Still, they need trade and assistance from America and are always happy to take the millions of dollars America offers for eradication programs. Some of it might even go toward eradicating coca crops. Most of it will wind up in the pockets of the politicians and business elite.

As far as the people here are concerned, the cocaine epidemic is America's problem. Our national addiction has created the industry and funded brutal drug cartels that often have more power than the governments down here. In Colombia, for example, politicians and judges who don't acquiesce to the drug lords are periodically kidnapped or assassinated. As Camillo likes to say to me, “Why don't you tell the Americans to wipe their noses and stop sniffing cocaine? Then we will have nothing to sell to you. End of problem. Don't come running down here blaming us and telling us what to do.”

Each day of the summit I go live from the NBC headquarters, reporting for our evening news on WBZ. I feel closer to the possibility of a network job when I meet the networks' Miami bureau chief, Don Browne, here to run NBC's coverage. He's dynamic, in charge, constantly projecting a sense of contained authority. As we talk, it's like the job is sitting there in front of me on his desk and I can almost reach out and grab hold of it.

At night, I head into the elegant old city to eat at Paco's, owned by Camillo's close friend Paco De Onis. His world-class restaurant is a two-story villa of white plaster, stone floors, and broad wood-beam ceilings. Camillo, here from Bogota to report for his national radio show, always joins me for dinner.

Tonight the restaurant is cordoned off by heavily armed Colombian military police. Immediately curious, Dennis and I push up to the cordons. A guard with an automatic rifle gestures for us to leave.

I flash the badge I have for the summit. It's meaningless, but it looks official. Before he can even look at it, Dennis and I slip past him, ignoring his shouts for us to stop. It's a simple ploy. Stop and he might arrest us, or keep going and he'll think we must be authorized to be there. It usually works like a charm, and this time is no exception.

At first, we can't figure out what's happening. Finally, we get to Paco's and see it's surrounded by more guards. Because we made it through the outer cordon, they readily grant us access. Once inside, Camillo is shocked to see us. “How did you get in?” he asks with wide eyes. “The presidents and their men are here. I had trouble getting in myself.” He means the presidents of Bolivia and Peru here for the summit, not George Bush. This is a Latin meeting. Off the record. Behind the scenes.

“We bluffed our way in,” I laugh as we greet one another with our usual hug. “Where are they?”

“They are upstairs,” Camillo says, referring to the presidents. He glances at Dennis's shoulder bag. “If you have a camera, do not take it out. Whatever you do, do not go upstairs.” I've never seen Camillo so intense.

I'm dying to shoot footage of this, but taking the camera out would be crazy. It would quickly be confiscated and we might be taken somewhere for a good beating. But I can't resist going upstairs. Shortly after our dinner arrives, I excuse myself to the bathroom. Then I slip up the curved stone stairwell. It's a lavish party. The room upstairs is filled with men I take for presidential aides and security agents. There are also several incredibly beautiful women, surely hired for the occasion. I glance around quickly, getting the best look I can before I'm noticed. I can't see any of the presidents. There's no way to ensure they're here except for the overwhelming anecdotal evidence. Why else would armed guards cordon off the street? And then there are Camillo's warnings. He always knows what's going on and who the players are. Still, I can't confirm anything and I've already pushed it too far.

On a coffee table I see a large, oval tray made of crystal. There's a huge mound of sparkling white powder in the middle, like a pyramid. Cocaine. Pure cocaine. I see a razor blade and a few thin lines,

three or four inches long, waiting to be snorted. Now I realize how dangerous it was to come up here. What a summit. Promises of cooperation during the day. Something else at night. If only I could turn on a camera. Film anyone involved with the drug summit. Get video of the coke. The world-class escorts. It would be a monster story. Everything would stop in its tracks. The summit would crash. An international incident. Oh God, would I love to bag this one.

A muscular looking man in an expensive black suit steps over to the tray, leans over, and snorts up a line of cocaine. He straightens back up and glances at me as he sniffs his nose. Then he does a double take. He's alarmed. I act casual but get downstairs as fast as I can, blending in with the crowd.

Sitting for dinner with Camillo and Paco, I don't speak a word about what's upstairs, but I can't stop thinking about the camera on the floor by Dennis's feet. I'll risk almost anything for a big story. But this wouldn't be a risk. It would be insanity. I can hardly imagine our fate if we tried to pull this off and got caught.

Refining cocaine is a hideous process. It begins in rustic laboratories called

pozos

, typically hidden in the tropical mountain forests.

Pozos

look like anything but labs. They're created by digging large pits in the earth under the cover of the jungle canopy. Tons of coca leaves from farms blanketing the hillsides below are transported in on the backs of mules. Hundreds of gallons of kerosene are poured into the pits, and local children are recruited, often by force, to stand in the sludge for up to twelve hours a day, stomping it with their bare feet. This leeches the cocaine alkaloid from the coca leaves. The soupy mixture is shoveled into large sieves strung between tree branches. The kerosene trickles out through the sieve, leaving behind a thick yellowish paste called

basuco

, which is then loaded into burlap sacks for transport to much more sophisticated city labs.

After the summit, Dennis and I set out to produce a series of in-depth reports on the origins of cocaine. We fly to Bolivia and then helicopter into the mountains above the city of Cochabamba

with a heavily armed Bolivian military strike force, funded by the United States as a result of the drug summit, seeking to destroy as many

pozos

as it can discover. Smoke plumes from fires built to keep the workers dry and to cook their food are always the tip-off. As soon as he spots one, our pilot manages to land in impossible places. As he's touching down, we jump out with the troops as they invade the lab. The noise of the chopper tips off the refiners and they flee before we arrive. It doesn't matter. The labs are the real target. The strike force burns down every one it finds simply by sloshing the

pozo

kerosene over everything and tossing in a match. This

hardly puts a dent in the trade, but it shows that Bolivia is doing something with the millions of dollars of American aid it's receiving.