Warrior Pose (4 page)

Authors: Brad Willis

Tall, conical minarets with onion domes tower over the city; from these, the faithful are called to prayer at the mosques five times a day. Traditionally, a devotee called a

muzim

climbed the winding staircase to a narrow ledge atop the minaret to call to the village at the top of his lungs. No one would hear him today. So great bullhorns have been attached to the minarets, wired to tape players down in the mosques. It's a sign of progress, Pakistan style.

Brockunier has somehow managed to get us into Mahabat Khan, Peshawar's largest mosque, to film the prayers. He blends in easily, wearing his own travel-worn

shalwar kamiz

and

pakol

while speaking the local dialect with fluency. Dennis and I stick out like sore thumbs, standing behind our TV camera and tripod in our blue jeans and khaki shirts. We look like aliens, or at least two futuristic men who hijacked a time machine and landed in a past century.

The mosque dates back to the 1600s and is stunning with its high, arched gateways, richly carved parapets, and fluted domes crowning a massive prayer hall. There must be more than a thousand people here. Rows of men with heavy beards sit on their heels chanting prayers in Pashto as they reach their arms to the sky in unison and then bow forward, touching their foreheads to their prayer rugs. More than a few of them gaze up at us as they lift their heads, their thick eyebrows knitted in frowns of disapproval. Even though America is an ally of Pakistan, and the country is happy to take billions of dollars in U.S. foreign aid, nobody said they have to like us. And most don't. They don't like our politics, our lifestyles, our culture, or the power we wield in the world. The only thing worse than an American right now is a Russian. It's an open secret that the CIA is funneling aid to the Afghans to fight the Russians, so we are tolerated. As the old saying here goes,

the enemy of my enemy is my friend

.

Brockunier is good at getting us around the streets of Peshawar, moving by foot from mosques to marketplaces so we can shoot the necessary background color for our reports. But we have to be careful. Everywhere we go someone becomes resentful of our presence, raising his voice at us. A crowd gathers. Tempers start to flare. We quickly commandeer some mini-taxis and get the hell out of there before the crowds become anti-American mobs.

At almost every location we film, Brockunier stops to buy Afghan rugs from street vendors. I can't understand it. He has thousands of rugs back in his shop that will take him years to sell. He's even begun pressing me for funds to buy more. Worse, he's having trouble making contact with the Afghan mujahideen, which is, of course, the reason why we're here. It's been five days now and I'm starting to wonder if my judgment was flawed and all I've done is sponsor a maniacal rug-buying spree for a complete crackpot. I have a sickening vision of walking back into the WBZ newsroom, tail between my legs, everyone staring at the failure I have proven myself to be as I break the news to Stan, and then start looking for another job.

Every night, Dennis and I sit in one of the two decrepit and mostly empty “foreigners' hotels” as Brockunier disappears into the dark streets to seek out his Afghan contacts. These are the people he has worked with for years, he tells me, and the only ones who can get us into Afghanistan. They always have to stay in hiding, and the dangers of meeting with us get greater every day. The longer we're here, the more people are aware of us, the more visible we become.

Peshawar is filled with intrigue. Soviet agents, secret police, spies, and snitches. Everyone on the lookout for an enemy or a chance to sell some information. A Soviet spy would kill an Afghan freedom fighter in a heartbeat, and vice versa. A bomb went off two nights ago at the other foreigners' hotel, destroying several rooms and injuring some European businessmen. Yesterday, there was an explosion at the Afghan restaurant we've eaten at every day.

Tonight, after a sixth day of waiting for contact with the mujahideen, I can't sleep. I'm furious with myself for trusting Brockunier and am contemplating storming into his room, confronting him, and tossing all his lousy rugs into the street while I'm at it. It's almost dawn when I doze off. Then I'm startled awake by a soft but firm knock at the door. I crack it open to see Brockunier standing there with two rugged men in Afghan dress. One is brandishing a Soviet AK-47 automatic rifle. The other looks like he could kill someone with his bare hands. It's the most comforting sight I've seen since we landed in this country and I feel embarrassed for losing faith in my friend who buys all those fabulous carpets.

“They have to blindfold us,” Brockunier says as I rouse Dennis from his bed. “They don't want us to know where the safe houses are in case we're captured and interrogated.”

One of the mujahideen pulls strips of dirty cloth from his baggy pajama pants pockets and wraps them around our heads to cover our eyes. Then we're stuffed into the back of a Jeep and driven to a safe house somewhere in the maze of the oldest sector of the city. When the blindfolds are removed, we're in a dark cement room, surrounded by a half-dozen or so mujahideen sitting cross-legged on an ornate rug. They look tough as grizzly bears but welcome us with warm smiles as they gesture for us to sit and drink chai with them. As I'll soon learn, nothing happens in Pakistan without this ritual of sitting on the floor and sipping tea as we are subtly scrutinized and deemed to be trustworthyâ¦or not.

After several meetings, each time at a different safe house, we finally win their trust. One morning before dawn, the mujahideen arrive at our room again without any notice. They give us a few minutes to

gather our gear, then load us into the back of their Jeep, this time for the dangerous journey through the wild, tribal territories along the border and into the snow-covered mountains of Afghanistan. There's no need for blindfolds now, but we need to lay low and do our best to blend in. Along the way, we stop at a tailor's shop and quickly get outfitted with Afghan clothing. All we need now are beards down to our waists and AK-47s slung over our shoulders.

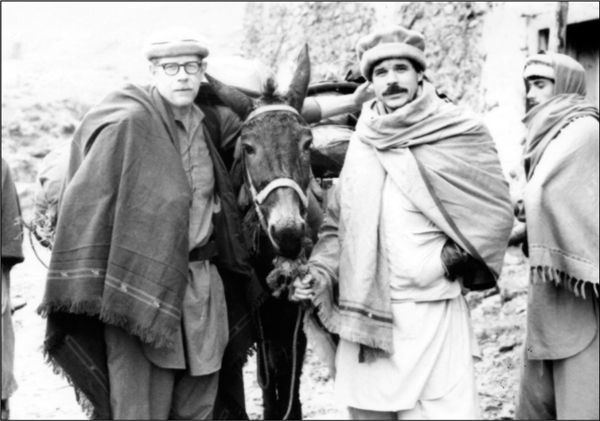

With Charles Brockunier inside Afghanistan in 1986.

The tribal territories line the amorphous border between Pakistan and Afghanistan. They begin on the sloping plains that skirt the Himalayas and soon rise into jagged mountains. The main crop in this region is poppy flowers, grown to produce opium and heroin. Warlords hold sway here. In the few remote towns we have to sneak through, weapons are openly sold on the streets and frequently fired into the airâsort of a test drive of your AK-47 or Kalashnikov before you take ownership of it. Dennis and I stay curled up in the back of the Jeep on top of our gear. There are informants everywhere, and we would be a prize catch.

“Are you doing okay?” I ask Dennis.

“Fine,” he says with an impish smile. Dennis looks like a shorter, tougher version of Brockunier, with his ruddy Irish face, short-cut reddish beard, and broad shoulders. He's strong as an ox, funny and charismatic, and utterly fearless. He's also the best photographer I've ever known. He never misses a shot and always manages to step squarely into the action without ever getting in the way.

“I'm just thinking about the gear,” he says. “I hope the solar battery recharging kits work right. I tested them before we left the States, but you never know.”

I don't have any doubts. Dennis keeps everything meticulously organized and I've seen him instantly repair his gear in the midst of a big story. He's unstoppable.

Brockunier is seated right in front of us, on the backseat of the Jeep with our guide and interpreter, Rasoul. The mujahideen with the AK-47 rides shotgun while his partner speeds across the rocky dirt roads. Every five minutes we hit a huge bump and our heads slam into the roof. We're choking on dust. It's hot as hell. And I love every second of it.

It's pitch black when we finally get through the territories and into the mountains of Afghanistan. We're driving without headlights, still going so fast that I can't believe the driver can stay on the winding road guided by starlight alone. But at least with the cover of darkness Dennis and I can finally poke our heads up and breathe more deeply, relieved that we've made it without having to get through any checkpoints.

“The border guards come and go,” Rasoul says in perfect English as we head higher into the mountains. “None can be trusted. We must still be very careful.”

Rasoul, which is surely a pseudonym, has thin, fine features, like a nobleman. In talking with him, I can see he is highly educated and cultured. He is fluent in English, French, German, and Russian in addition to all the major Afghan dialects. He loves conversation, but he is cryptic about his past, except for sharing that he is from Kabul, the capital city of Afghanistan. My guess is that he's a member of the Afghan elite, deeply connected to the government and business community, maybe even a former head of some intelligence operation. I imagine he would have been imprisoned or executed had he not escaped Kabul during the Soviet invasion. Rasoul is vehemently patriotic and devoted to the resistance, moving like a shadow behind the scenes. He has to be the contact Brockunier was waiting for all along. The one person making all of this happen.

It must be close to midnight when I nod off to sleep. Suddenly, our driver slams on the brakes and my forehead smacks into the metal bar framing the backseat. “Get down!” Rasoul hisses with urgency. “Say nothing! No one speak! I'll do the talking. Do not leave the Jeep!” He speaks like a general and we immediately fall in line. Brockunier freezes like a statue. The mujahideen who is riding shotgun grips his automatic weapon and holds it at his chest. Dennis and I curl up again, trying to disappear.

As Rasoul jumps out of the Jeep and slams the door, Brockunier whispers, “We're surrounded by armed men in military uniforms. They're speaking Urdu, so they're Pakistanis. This isn't good.”

I can hear Rasoul arguing loudly. I don't understand a word, but it doesn't sound like he's getting anywhere. Suddenly, the Jeep is flooded

with flashlights, the doors are thrown open, and we're ordered out. Brockunier seems to pass for one of the mujahideen despite his reddish beard. But Dennis and I, even in our new pajama-like garb, still look very much like foreigners.

Rasoul is ordered back to the Jeep and whispers, “Don't say a word. These are tribal people. They don't speak English, but they know it when they hear it. They hate Americans almost as much as Russians. I've told them you are French doctors, volunteering to treat the wounded. Right now, they are threatening to arrest us all. Whatever you do, do not show your passport.”

Three guards walk up and yell at us to get out of the Jeep, then quickly rummage through everything, finding our camera gear beneath the duffel bags filled with Brockunier's medical supplies. This stops the show. The yelling gets louder. Rasoul is incredibly courageous, alternately confronting the armed men with verbal assaults then switching to gentle persuasion. But he's getting nowhere. Finally, he somehow manages to get the guards to wait in a group as he comes back to where I'm standing at the rear of the Jeep.

“This is trouble,” he says with a sigh of resignation. “They want to know what doctors are doing with camera equipment. They want documents.”

My mind starts racing for some sort of solution. It's too dangerous to change our story and tell them we're journalists. There's no way we can show them our American passports. Then it hits me in a flash. “Tell them I'm getting documents from my bag,” I whisper to Rasoul.

He looks shocked and is about to protest when I say, “Don't worry. No passports. Trust me.” Rasoul calls out to the leader of the guards and gets his permission as I slowly reach into the Jeep for my shoulder bag and open the zippered pouch I keep my passport in. Right next to it is the equipment manifest we had to obtain from the Pakistan Embassy granting permission to bring our gear into the country. It's covered with official government stamps.

“Tell them this is our permission document from Pakistan customs,” I whisper to Rasoul. The first two words beneath the government stamps are Sony Betacam. That's our digital camera. “I'm Dr. Sony,” I whisper to Rasoul, pointing at the words. “Dennis is

Dr. Betacam. We're treating wounded fighters and filming it to raise more money back in France for more medical supplies. We're on the side of their Afghan brothers.”

Rasoul's eyes widen. “This is good,” he says as he takes the paper and walks toward the guards. There are a few tense minutes. The document changes hands several times. Suddenly, everyone is patting Rasoul on the back. Our gear is returned to us and we cram back into the Jeep, start the engine, and roll past the guards, waving and smiling like one big family.

“I have to remember this trick,” Rasoul says as he hands the manifest back to me with a huge sigh of relief.

“I thought we were dead,” Dennis says. It's the first time I've ever heard him sound frightened.