Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (39 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

In any case, in “Joe Gould's Secret,” published in 1964, after Gould's death, Mitchell does something he never did before: he lays bare his own thought processes, reactions, and ambivalence. And he becomes a character himself in the process. In his other profiles, Mitchell would sometimes refer to the subject as “my friend,” but then quote the person at length with journalistic impersonality, not allowing the give-and-take of a genuine friendship to appear on the page. This time we see Mitchell's relationship to the profiled subject vividly: the “I” character, Joe Mitchell, perennially oscillating between generosity and self-protective indifference, charmed gullibility and disenchantment. In this, the longest piece he ever wrote, he charts the course by which Professor Seagull became an albatross around his neck.

I find especially intriguing his revisiting the first set of meetings with Gould, the very material he had shaped in “Professor Sea Gull,” this time admitting to his uneasiness, boredom, and revulsion at the time, which led him on occasion to put off the importuning wraith. Even after Mitchell's

narrator has divined Gould's secret, he can still not entirely shake this doppelgänger—or his lingering feelings of responsibility for him. In the end, Mitchell's narrator comes to discover that Gould has been merely rewriting (without improvement, necessarily) the same two essays over and over, his entire life: one about the death of his father, one about tomatoes. The pathetic stack of manuscripts left posthumously, all with the same two titles, induces textual vertigo, like something out of Borges. When he concluded, however, with “ ‘God pity him,’ I said, ‘and pity us all,’” I bet Mitchell was thinking not of Borges but of Melville's “Ah, Bartleby! Ah, humanity!”

The psychological depth and rounded characterizations achieved in “Joe Gould's Secret” can be read backward as a self-critique of the earlier profiles. Of course, by calling “Joe Gould's Secret” Mitchell's masterpiece, I am in part expressing my own literary preferences, because here is a true personal essay, and a double portrait, with a fully developed, shaded narrative persona—the kind of thing I like best.

THE ACHIEVEMENT OF

The Bottom of the Harbor,

which is Mitchell's strongest essay collection overall, was based less on individual portraiture than on his success in rendering a complex environment. Combining the perspectives of marine biologist, geologist, urbanist, anthropologist, and historian, he succeeded in unraveling the interdependent strands of past and present, nature and humanity, predators and prey, economics and culture, all in the most elegantly accessible prose. His vision of the harbor had a startling ecological prescience: in the 1951 title essay, he was writing about water pollution, landfill, garbage disposal, dredging, and all the interrelationships between creature and environment that were being altered by modernity.

“The bulk of the water in New York Harbor is oily, dirty, and germy. Men on the mud suckers, the big harbor dredges, like to say that you could bottle it and sell it for poison. The bottom of the harbor is dirtier than the water. In most places, it is covered with a blanket of sludge that is composed of silt, sewage, industrial wastes, and clotted oil…. Nevertheless, there is considerable marine life in the harbor water and on the harbor bottom. Under the paths of liners and tankers and ferries and tugs, fish school and oysters spawn and lobsters nest.”

Mitchell's uncanny ability to envision the world undersea is reminiscent of the dragger captain he profiles, Ellery, who “thinks like a flounder,” or Roy, who has “got the bottom of the harbor on the brain,” or the old rivermen who “fish around in their memories.” Mitchell's imagining of the ocean floor has an allegorical dimension: the harbor is the inside of his skull.

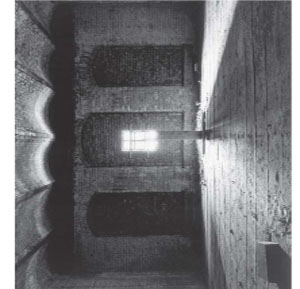

The essays hint at other allegorical meanings, some topographically derived (“Up in the Old Hotel,” “The Bottom of the Harbor”), some expressing a whimsically Gothic inclination. When Louis, the owner of Sloppy Louie's, finally makes his way into the boarded-up floors above his restaurant, the decor of decay he finds has echoes of Poe and Hawthorne. There is a Gothic sensibility working as well in the claustrophobic, obsessive accumulation of detail—or the rats that leap out of drawers, “snarling.” Mitchell confesses a persistent Southern taste for cemeteries, hell-and-brimfire preachers, and “people with phobias, especially people who predict the end of the world.” Foreshadowings of apocalypse keep wandering into these harbor essays: “The Last Judgment is on the way, or the Second Coming, or the end of the world,” says a boatman looking at the New York skyline; others warn that the world is going to hell in a handbasket; even the equable black deacon, Mr. Hunter, broods, “It'll all end in a mess one of these days,” and worries about “the prophecies in the Bible,” when “the dead are raised.” The occult and the esoteric are never far removed: they are to be found in biblical visions, in the secrets of old men and women, and in Joe Gould's “underground masterpiece,” hidden somewhere. It is as if Mitchell were always hoping to decode signs of eternity in the prosaic world around him. Few writers possess a sense of the daily and the apocalyptic in such close proximity.

In “Joe Gould's Secret,” Mitchell confessed that as a young man he had planned to write a novel about a reporter, coming to New York, who “often sees the city as a kind of Hell, a Gehenna.” While he never wrote that overly symbolic novel, neither did he ever give up entirely his Revelation-inflected reading of the modern city. There is a dark, morbidly transcendental undercoating to his otherwise sunny pieces, at once powerful and frustrating, as in any private allegory whose meanings can only be partly surmised.

JOSEPH MITCHELL published nothing else after “Joe Gould's Secret.” For the last thirty years of his life, he continued to report to work. Sitting in that office year after year, not writing (though his typewriter could sometimes be heard: then let us say, not writing anything he deemed of sufficient worth to let into print), he became, in a sense, Joe Gould, a malingerer bluffing a great manuscript that no one would ever see. He was allowed to retain his

New Yorker

office for decades after he stopped publishing, becoming the sentimental mascot of the magazine, even more principled for keeping his silence, or for refusing to relax his high standards by venturing again into vulgar print. He was the dotty but lovable uncle in

You Can't Take It With You,

who would emerge from his room from time to time and be given a choice seat at the banquet.

Many have speculated on his writing block. Could be he'd said all he had to say. Could be that the implications and vistas opened to him by “Joe Gould's Secret,” of planting himself in the narrative, frightened him. Moreover, it wasn't only Mitchell who stopped writing profiles of the common man. As the city's demographics altered, it seemed more awkward for white journalists to cast the newer, darker-skinned faces in the role of New York's Everyman. All those amusing sketches of curbstone characters, such as A. J. Liebling's cigar store owners and tummlers, came to a halt, as white journalists hesitated to portray minority entrepreneurs or street-corner society in droll, local-color profiles, and minority journalists were in no mood to patronize their own. Perhaps, too, regardless of ethnicity, the new reporters with their journalism-school degrees felt farther away from the man in the street than their school-of-hard-knocks predecessors had.

Russell Baker, in an appreciation of Mitchell for

The New York Review of Books,

asserts that the author stopped writing because the city had grown too harsh and uncivilized: “But the New York emerging in the 1960s was not a city that lent itself to his particular ‘cast of mind.’ It needed writers who had grown up hearing the roar of the bullhorn, not the voice of Aunt Annie talking about the people down below.” Also, Baker says, the age had grown too narcissistic for Mitchell: “He was trained in the hard discipline of an old-fashioned journalism whose code demanded self-effacement of the writer. A reporter's effusions about his own inner turmoil were taboo.” Myself, I don't see the point of invoking Joseph Mitchell

as the last decent man whose writing block chastises the rest of us for our vulgarity and egotism. There was plenty of unsettling loud noise in New York during Mitchell's prolific periods, and there were plenty of star journalists who put themselves in the story. No, I rather think his silence had more to do with aging. It is hard for an elderly man to keep seeking out those still more ancient, and he refused, reasonably enough, to learn from youth.

In the interim, a cult had grown around him. His out-of-print books, which he refused to allow reprinted (in the same way that he refused to be anthologized), were collected and hoarded by bibliophiles, especially those with an interest in urban sketches, old New York, or the golden age of

The New Yorker.

I remember once visiting some journalists in Hoboken, who had made a sort of shrine to Mitchell in their bookshelves. Eventually he accepted an offer from Pantheon Books to reissue a large, handsome edition of his work, in 1992:

Up in the Old Hotel,

for which he received the Brendan Gill Award, given to the year's greatest contribution to New York culture. Sitting at the awards luncheon among his admirers, he seemed a courtly, birdlike presence, enjoying his meal and rising to accept the compliments of strangers (including myself ).

A few years later, in 1996, he passed away. And now he is both one of the gods of American nonfiction, and largely forgotten and unread—a combination not entirely paradoxical if you consider the low esteem in which belletristic, nonfiction prose is held in our culture.

When I walk the waterfront, sometimes feeling a courtly apparition at my elbow, I am tempted to call out, “Joe, is that you? What do you make of what they're doing to your harbor?” He found

his

waterfront real. That was the whole thing in a nutshell. It seems a dubious, wishful idea: that reality only adheres to the poor, the derelict, the grimy, the wet; that the powerful are abstract and unreal. Still, we've all had that feeling at times.

19 THE SOUTH STREET SEAPORT (CONTINUED)

I

WAS WANDERING AROUND THE SOUTH STREET SEAPORT AREA WITH BARBARA MENSCH, A PHOTOGRAPHER WHO HAS LIVED IN THAT NEIGHBORHOOD FOR DECADES AND HAS SEEN all its changes. Barbara did a great series of photographs on the Fulton Fish Market, which became a book. She remembers when Peck Slip was a very important part of the fish market: on winter nights all the oil cans were lit with fires, the fish were laid out, and the hand wagons rumbled over the cobblestones. At 40 Peck Slip, she says, there used to be something called the Club on the second floor (above the present Market Bar), where numbers, loansharking, and other recreational activities of an ille

gal nature went on. Crime, says Barbara, was an accepted part of the fish market scene. Security guards who had just gotten out of the can themselves for theft would be hired by the stall owners. The market, she says, was not about fish so much as it was about survival, trying to keep afloat a way of life (“call it

goombah

or white ethnic working class or street smarts”); it was living by your wits with improvised cons at the border of legality. In the end, that way of life could not survive here: it fell to the corporations and realtors who call the tune in this city, and who practiced a smoother type of dishonesty, breaking their promises to the fish-dealers.

Barbara spoke warmly about that period in her life when she was gradually accepted by these rough, sentimental men, enough to let themselves be photographed and interviewed, and to let her hang around all night watching the market operate at full blast. The only other women who were down there were prostitutes, she said.

Barbara is slender, small, and intense; everything she brings into a conversation she cares so deeply about that, finally, neither of you knows how to get her back to a calmer, more mundane place, except by interrupting her brusquely and changing the subject, which tactic she seems not to mind at all. A single mother, she exemplifies a certain type of scarred, courageous New York City woman; then she'll lighten up, especially looking at the city she loves, and start to laugh.

She remembers when an icehouse stood on the old dock where Pier 17 is now, and the fish were sorted there, fresh off the boats. She remembers going to community meetings and trying with others to talk the Rouse Corporation into saving more of the fish market and the surrounding atmosphere. But New York was undergoing severe financial difficulties at the time, and the Rouse Corporation, which had made such a success of Boston's Faneuil Hall (and was about to do Baltimore Harbor), held the upper hand in negotiations with the city, and demanded several concessions that would make it more like a shopping mall: some old buildings at Peck Slip were torn down, the sidewalks were widened, and a large, signature “festival marketplace” pavilion was built out on a pier. Pier 17, this big, red, barnlike structure with its chain boutiques and overpriced, vista-offering restaurants, which I hated when it first appeared (what do red barns have to do with the waterfront?), now seems to me tolerable, harmless, almost benign. Its best feature is a bleacher view of the harbor—one

of the most dramatic places from which to watch what is left of the East River boat traffic; and, if not the “instant urban landmark” of “vernacular waterfront architecture” the

AIA Guide

proclaimed it to be, in any event it is not what is essentially wrong with the South Street Seaport. For that, you have to cross the street to the inland side.