Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan (59 page)

Read Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan Online

Authors: Phillip Lopate

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Essays, #Biography & Autobiography, #General

We are “beached.” Now I know the meaning of that term in a personal way I never did before. There are

Survivor

jokes aplenty. Everyone is sitting down on the sand, conserving energy. It has begun to drizzle. John puts on a poncho, and I eye an old blue sweater in his pouch. He is kind enough to let me borrow it, saving me from hypothermia.

Gazing at the becalmed inlet, I think about the other catastrophic history, besides Typhoid Mary, for which North Brother Island is noted: it was here that the burning excursion boat

General Slocum

was beached. On June 15, 1904, 1,358 passengers, mostly women and children, German-born or of German descent, parishioners of St. Mark's Lutheran Church on the Lower East Side, boarded the

General Slocum

at the pier on East Third Street for their annual Sunday-school outing. The steamboat headed up the East River as the band played the Lutheran hymn “Ein Feste Burg Ist Unser Gott.” Ten minutes after the boat had left the dock, fire broke out in the storeroom. There followed a succession of errors, which turned what should have been a minor problem into a grisly massacre of the innocents. A drunken deckhand poured a bag of charcoal onto the fire to arrest it; the crew panicked; the skipper, Captain William Van Schaick, inexplicably ordered the boat to continue north, instead of docking it at 125th Street. Meanwhile, harbor barges and tugboats, seeing that roaring furnace on the water, offered to help, but the captain ignored them all, pounding the boat upriver. A port rail gave way, sending hundreds to a drowning death; children burst into flame; mothers sacrificed their lives; and still the ship continued on its course, until finally it came to a stop at North Brother Island.

According to a contemporary account in

Munsey's Magazine

by Herbert N. Casson, “North Brother Island is used as a place for the city's sick, but

it now became a place for the dead. The limp, charred bodies were laid out in long rows on the grass…. By midnight six hundred and eleven lay on the lawn and four hundred more were still in the river…. The doomed ship had scattered its living freight over two miles of the river's length, and for days the bodies were picked up and brought to the island of sorrow.”

In all, there were 1,031 casualties, making it the greatest nautical disaster up to that point in history, and the outcry would undoubtedly have provoked much reform legislation, had it not been for the fact that laws already existed on the books to prevent just such a debacle. In the investigations that followed the disaster, it was learned that every possible safety measure had been compromised by the steamship company's penny-pinching management: the life preservers were ancient and rotten, and filled with cork dust; the cheap water hose burst apart in three sections; the life-rings had been reinforced with iron, condemning those who used them to sink instantly; the lifeboats and rafts were wired to the deck; the ship carried barrels of hay and oil, against regulations; the requisite steam valve in the storeroom was missing. The inspectors of New York Harbor had been corrupt and negligent. The crew, consisting of underpaid, unskilled landsmen who had never been given a fire drill, had, instead of assisting the passengers, dived overboard, saving their own skins. It is some comfort to know that the captain later did ten years' hard labor in Sing Sing, though the Knickerbocker Steamship Company escaped punishment.

Kerlinger makes a call on his cell phone, and learns that the tide will not come in again until 11:00 P

.

M

.

I imagine the effect of phoning my wife on his borrowed cell phone and telling her not to wait up, I will not be taking her out to dinner or helping move things out of the basement for tomorrow's stoop sale, as planned, because I am moored on an island off the Bronx. That should go over well.

“Don't worry,” Kerlinger says, “we don't have to spend more than a half hour on South Brother Island. I can do estimates from a few samplings, as long as I set foot on the place.”

I am less and less interested in seeing South Brother Island. It appears I have been bitten by something, and I look down at my ankle to see if it is a mosquito bite or the ringlike formation that is an initial symptom of Lyme disease. The itch is ferocious.

Bob and Kerlinger get into a discussion about birders, of which there are more than sixty million in the United States. Kerlinger thinks they ought to organize more effectively and sponsor a strong lobby in Congress. Bob says, “Birders are not good collective types, they're loners,” with that apologetic grin of his.

John suddenly whips off his pants, revealing a pair of swimming trunks underneath, and decides to wade in the water regardless of how squishy it is. “Just call me Muck Boy,” he says. The tide is so low that he can walk all the way out to the boat with the water no higher than his waist. He returns, and gets two volunteers (not me) to join him in trying to push the boat out of the mud. Though they again fail to budge the Parks Department boat, they think that the combination of their pushing from the front and the other boat towing with a rope from the back will dislodge it. After another half hour of coordination, the second boat approaches, and the maneuver works.

Now both boats stream off to the other side of the river. We wait. A half hour passes, during which we speculate what might be happening, and why they do not try to rescue us. The boats seem fused, mated involuntarily, like dogs copulating. Kerlinger takes out his cell phone and calls the Parks Department boat, which notifies him there is a problem with the cooling system. They are trying to repair it.

Another hour passes. Cancel the

fätes galantes;

I see why there are no plans to develop any public access to North Brother Island. Not that they couldn't overcome the problems—build sturdy piers, use more powerful boats—but at the moment I am feeling bested by nature. “New Yorkers were right to turn their backs on nature,” I tell John. “See how these tides screw you up?”

“It's true, Baltimore Harbor and Boston have tides that are much gentler.”

I cadge a slice of Italian bread from Bob. We have moved up the shore to a slightly deeper anchoring point, from which we watch the maneuvers of the two boats, tacking back and forth across the river to no discernible purpose. There is no longer any question of stopping at South Brother Island, Kerlinger has long ago given up that plan.

We have been waiting three hours to be delivered, when the Parks

Department boat returns, the crew telling us that we are all to climb aboard this one craft (exceeding its capacity, according to earlier warnings). The second boat will follow us in case something bad happens. The Stranded Six wade into the water and belly-flop onto the boat in seconds flat, so passionately do we want off the island. On the boat we decide it has been an “adventure”—a word applied to experiences that end in rescue.

28 HIGHBRIDGE PARK

H

IGHBRIDGE PARK RUNS TWO AND HALF MILES, FROM THE POLO GROUNDS HOUSES AT EAST

155

TH STREET ALL THE WAY UP TO DYCKMAN STREET (THE EQUIVALENT of 200th Street). For most of that length, it faces the Harlem River. Next to the water there is a tiny strip of all-but-unwalkable “esplanade,” then comes the Harlem River Drive, then, looming above the roadway, the precipitous Highbridge Park. Aside from the housing projects, it is

the

dominant presence on the Upper East Side waterfront, north of 96th Street. Almost as long as Central Park, it constitutes a major chunk of

Manhattan's parkland acreage, yet remains unknown—hidden in plain sight, you might say. Mention Highbridge Park to most knowledgeable New Yorkers and you draw a blank. (Had you asked me before I began studying the Manhattan waterfront, I would have been similarly ignorant.)

Despite abutting a dense barrio, it is the most underutilized major park in the city. One reason is its rugged topography: on the edge of a bluff, the Manhattan Palisades, it slopes steeply downward, which affords wonderful views of the Harlem River Valley but few opportunities for picnicking. In the nineteenth century its vistas included the last remaining farms in Manhattan. Highbridge Park was designed by Calvert Vaux (Olmsted's partner in Central Park and Prospect Park) and Samuel Parsons Jr., and initially, when it opened in 1888, it boasted many of the features in Vaux's previous parks, such as elegant wrought-iron railings and fieldstone walls. Polite society would watch from semicircular overlooks the horseraces down below, on the Harlem River Speedway, before it was motorized.

Over the twentieth century, however, it fell into neglect. As the neighborhood around it grew poorer, it began to suffer from budgetary inattention; and it had no recourse to the private philanthropic assistance that propped up Central Park and Riverside Park, which were adjacent to wealthier areas. It became, according to ex–Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, the city's “most damaged, most cluttered” major park—a repository for stolen, stripped cars and illegally dumped garbage. The guardrails were vandalized, the stone walls broken, the paths overgrown, the park signs stolen, the weedy flora allowed to grow as it might with little landscaping attention, until it turned into a near-deserted, formidably impassable wilderness.

Then, in 1997, the New York Restoration Project, which was founded by the entertainer Bette Midler, began to clean up Highbridge Park, working with the Parks Department to clear away the auto wrecks and the hundred of tons of debris, and planting flower bushes in their place. The park was tentatively declared suitable for visiting.

I began frequenting Highbridge Park over a period of several months. Each time I entered it I got lost. There seemed to be no discernible pattern of stone staircases leading to clearly marked gravel paths, as in other

city parks; or rather the pattern had become interrupted, overgrown, and unless you memorized your progression through the scruffy vegetation, you would be just as lost the next time. The stairs that existed were so crumbling that footing became precarious, and you had to take them very slowly. For the most part there was no clearly marked path downward, which left no choice but to crawl through the steeply sloping woods. Not that it wasn't fun to inch my way down through the thicket, gauging footfalls rock by rock so as not to twist an ankle, holding on to sturdier tree branches for balance. Whenever I reached a high rock, with signs of recent campfires, I would look down to ascertain what would be the least treacherous direction; some of the drops looked like sheer vertical cliffs.

One time when I was exploring Highbridge Park, I was amazed to find myself in a grove of highway columns, in the middle of a forest. It was like coming upon Stonehenge. I stood there listening to the clatter of trucks hitting uneven metal plates. It was in these lower, densely wooded slopes of the park that I always got lost. Still, there is something to be said for getting lost, particularly in a lucidly laid-out, gridded city like New York, where it has the charm of novelty. You can imagine yourself one of James Fenimore Cooper's heroes, picking up cues from a bent twig.

The top part of Highbridge Park, near the entrance at 174th Street, was much more intelligible. Coming from the subway, I would walk along Amsterdam Avenue past the Dominican men fiddling with their cars, past the local bodega, and into the park itself, where a spacious lawn sloped upward to the community swimming pool and the water tower. As long as I penetrated no farther into the park, everything made sense.

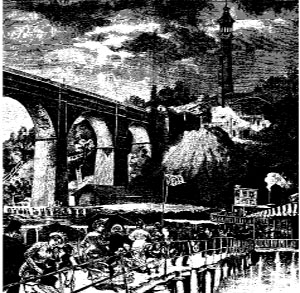

At East 174th Street, Highbridge Park holds two historically important engineering works, whose construction preceded it, and with which its identity will always be entwined: the High Bridge, and Highbridge Water Tower. The 1,400-foot High Bridge began life as a spectacular, Roman-style, fifteen-arched aqueduct that crossed the Harlem River. Taking ten years (1838-1848) to construct, it was part of a network of tunnels and aqueducts built to transport water from the Croton reservoirs in upper Westchester County south to Manhattan. This “Croton water” proved a great necessity, not only because New York's population was growing dramatically

during these years, but because the city's frequent, devastating fires and cholera epidemics could only be fought with large amounts of clean, dependable water.

In his book

Water for Gotham,

Gerard T. Koeppel tells the story of the conflict between low-bridge and high-bridge advocates. The latter solution, which won out in the end, was costlier but more architecturally refined.

*

Indeed, the High Bridge not only served as an aqueduct, it quickly became a treasured scenic landmark. Painters and sketchers of the day recorded its rhythmic arches at every opportunity; strollers adored it (Edgar Allan Poe used to cross over it regularly from his Fordham home in the Bronx); and pleasure steamers in the summer conveyed passengers every hour through the length of the Harlem River, via the High Bridge, depositing them at riverside cafés within clear sight of it. One picture magazine enthused, “The glimpse of the High Bridge from ‘Florence's,’ with the agreeable foreground of soft-shell crabs, oysters, and miscellaneous vials, suggested by our sketch, is an enjoyment which has been, and may, we trust, long be.”