We Are Not Eaten by Yaks (24 page)

Read We Are Not Eaten by Yaks Online

Authors: C. Alexander London

Sir Edmund clapped.

“Thank you so much, young lady,” he said. “That was entertaining. But I think we've had enough.”

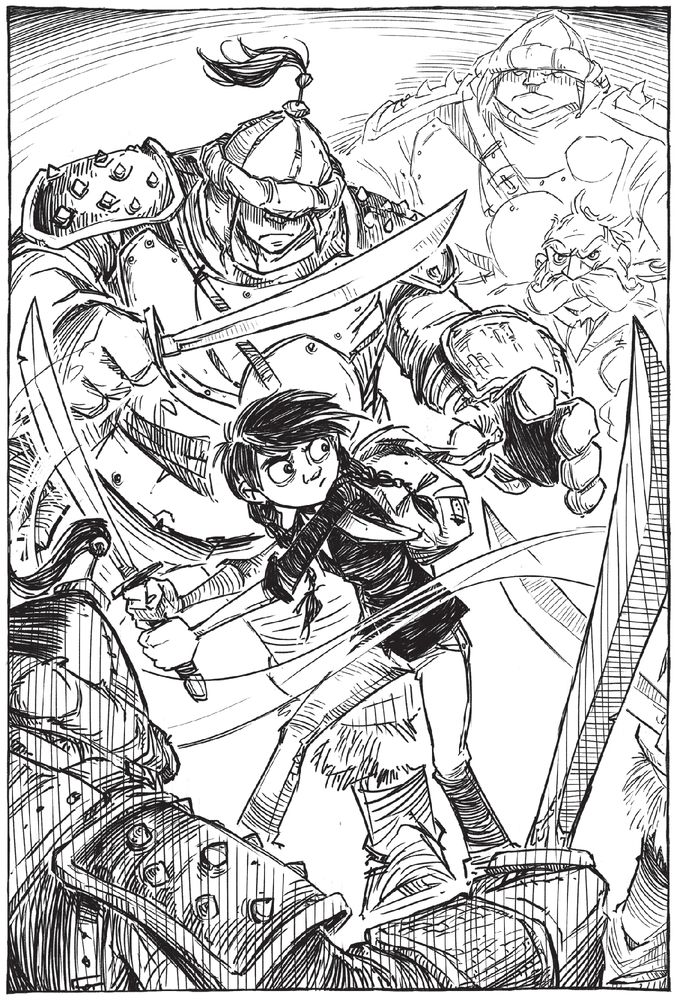

With that, the guards dragged Oliver and Celia kicking and screaming from the room. One of them snatched Oliver's backpack with a violent yank, nearly ripping out his shoulders. Celia bit her guard's hand, but he didn't seem to mind.

“I didn't know you could fight like that,” Oliver said as they were pulled along.

“Me neither,” panted Celia, still out of breath.

They reached a heavy wooden door with a big lock on it. A prison cell. The room had no windows or other doors. There were no statues with third eyes to press, or corners where strange monk-children could hide to come to their rescue. The guards tossed the twins into the room like rag dolls and slammed the door behind them. They heard locks and bolts slamming shut.

“This is bad,” Celia said.

“That wasn't much of a showdown,” Oliver agreed. “We mostly got beaten up and locked away.”

“Well, it's not like we've had much help. Our only friends so far have been a yak and a strange kid who might have been a spirit or just a weirdo living in a cave.”

“You really think Mom had us thrown out of the airplane? Why would she do that?”

“She had that symbol on her necklace in the picture, the same ring that the air marshal and the man in the shiny suit had.”

“And the people on the fake

Love at 30,000 Feet.

What do you think it means?”

Love at 30,000 Feet.

What do you think it means?”

“I don't know,” said Celia. “I just don't know. I can't figure all this out. How am I supposed to figure everything out? I'm only three minutes and forty-two seconds older! I can't do everything!” She was crying now. “I'm not like Mom and Dad at all. I'm not a genius or brave or adventurous. I'm just not.”

“Calm down.” Oliver hugged his sister. “It's okay. It'll be okay.”

“You don't know that,” she sniffled.

“Yeah I do.”

“How?” She wiped the tears out of her eyes.

“Because,” said Oliver. “At the end, when things look the worst, there's always a turnaround. It's a rule, just like the wire breaking. This is just how things happen. It's just good storytelling.”

Oliver knew a lot about good storytelling. You can't watch as much television as he did and not learn a thing or two.

“Not on

Love at 30,000 Feet,

” Celia sniffled. “That show's been on forever, and things always get worse. The Duchess in Business Class doesn't even know that Captain Sinclair is hiding his deep vein thrombosis.”

Love at 30,000 Feet,

” Celia sniffled. “That show's been on forever, and things always get worse. The Duchess in Business Class doesn't even know that Captain Sinclair is hiding his deep vein thrombosis.”

“That's that thing you get if you sit too long on an airplane?”

“Yeah.”

“I always thought it was some kind of musical instrument.”

“Well it's not. It's a serious medical problem. And the captain has it.”

“Well,

Love at 30,000 Feet

is different,” Oliver explained. “But trust me, in stories about kids in trouble, there's always hope.”

Love at 30,000 Feet

is different,” Oliver explained. “But trust me, in stories about kids in trouble, there's always hope.”

Celia sighed. Her brother was right. If this was anything like TV, there had to be a happy ending. It was about time for their adventures to be more like TV. So far things were not going at all like they should.

“All right,” she said at last. “We're going to make our own happy ending.”

“Okay.”

“Okay.”

“Good.”

“Yes.”

“Okay.”

“Here we go.”

Minutes passed in silence.

“Celia?” Oliver said after five minutes in the dark without a word or a sound.

“Yeah?”

“You aren't doing anything.”

“I thought you were.”

“What was I supposed to do?”

“I don't know. I just figured you'd do something. You know, all that good storytelling and happy ending stuff.”

“I was trying to make you feel better.”

“So we still don't have any way out of here?”

“No.” Oliver thought for a minute. “Wanna try meditating again?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Yeah, me neither.”

They sat in silence again. It was hard to tell how much time had passed in that little room with no windows.

“Why did that yak lead us here?” Oliver wondered after a while. “Why did Mom's picture show us this place if we were just going to be betrayed by that old abbot? If Sir Edmund was telling the truth, then Mom's trying to kill us too!”

“We were better off in the cave with that kid,” Celia agreed.

Suddenly, a loud gong sounded right outside their door. There was a moment of quiet and then it sounded again, louder.

BONG!

Everything was silent and then they heard the click and squeal of the bolt sliding back. The door opened and the room was flooded with light. The two guards were unconscious on the ground and the old abbot was standing above them holding a big gong. He smiled when he saw the children.

“I find that sometimes the sound of the gong alone is not enough to chase away evil,” he said. Then he stepped aside. A nun stood behind him covered in robes, her head bowed. She held their backpack out and Celia took it from her.

“Thanks,” she said.

“You're welcome, Celia,” the nun said, dropping the robes from her head and looking up. She had long dark hair and big dark eyes, and she was not a nun at all.

“Mom!” both children gasped.

“We have very little time,” said their mother.

32

WE ARE FAMILY

“I AM SORRY I BROUGHT YOU HERE

,” their mother told them quickly. “But it was the only way. I am proud you made it this far, but you still have farther to go.”

,” their mother told them quickly. “But it was the only way. I am proud you made it this far, but you still have farther to go.”

They could already hear guards coming around the corner toward them. There was no time for hugs or questions or tears. The monastery was usually a quiet place. The sound of two loud gong strikes and two bodies hitting the floor had certainly been noticed. The abbot dragged the unconscious guards into the cell, tossed the gong on top of them and shut the door.

“You go,” the abbot said. “I will delay them. It is the least I can do for bringing such misfortune to your family.”

Their mother nodded at him, then grabbed Oliver and Celia's hands and rushed with them down the hall. They slipped behind the door to the nuns' quarters just as they heard loud voices shouting at the abbot. Their mother stopped a moment to listen.

“What was that noise?” one of the guards demanded.

“It must have been a loud television,” the abbot explained.

“There's no television here!” the guard shouted.

“Oh, some of our monks have a weakness for the soap operas,

The Lovers at 10,000 Meters

and whatnot. It's really quite a fineâ” The abbot couldn't finish his bogus explanation. A guard thumped him on the head and locked him in the cell.

The Lovers at 10,000 Meters

and whatnot. It's really quite a fineâ” The abbot couldn't finish his bogus explanation. A guard thumped him on the head and locked him in the cell.

“This way,” Dr. Navel told her children.

“What's going on, Mom?” Oliver asked.

“I can't explain right now, Ollie,” she said. “I promise I will. But right now, we have to run, before things get really dangerous.”

“They already are really dangerous!” Celia whisper-shouted. “Sir Edmund said you had us thrown out of the airplane!”

“That was for your own safety. If you had landed in the capital, you would have fallen right into Sir Edmund's hands.”

“But we fell into his hands anyway!” Celia yelled. “And we could have died!” Her shouts echoed through the halls of the monastery.

“Honey, I know you're mad,” their mother said, looking around nervously. “But believe me, things will get a whole lot worse if we don't go right now.”

Without waiting for Celia to reply, she half dragged, half pushed them through a maze of hallways and chambers. Monks and nuns poked their heads out of doors and watched the Navels rush past. They all seemed to know Oliver and Celia's mother; they all wanted to help. As they rushed, Oliver and Celia heard shouting from down the hall. Nuns were arguing with guards.

“We will go where we please,” they heard Sir Edmund shout. “On the authority of the Council, let us pass! Ouch!”

Someone had hit him with a cooking pot.

“Here we are,” their mother said, stopping in front of a high window. The view looked out over a snowy plain, hundreds of feet below. In the distance, they saw the mountain where their father was held.

“This way,” Sir Edmund was shouting. “Those kids can't have found this place alone. They have help. I know it!”

Worry spread across their mother's face, but she hid it quickly.

“We have to climb out on the ledge,” she said, stepping up onto the windowsill and pushing open the glass.

“What?” Celia shouted, not even bothering to whisper-shout. “You disappear for three years, have us thrown out of an airplane, and now you want us to step out on a ledge thousands of feet in the air? We are only here because of you! Because of you and that stupid library.”

“She's just angry,” Oliver said, not wanting to hear his mother yelled at the first time he saw her in years, “because whenever we climb anything, we end up falling. I mean, really falling really far . . . like out of an airplane.”

“I'm sorry, guys. Excitement's still not your thing, is it? Well”âshe looked at Celiaâ“this time you won't fall.”

“Why not?” Celia crossed her arms and leaned back on her heels. She was in full-on stubborn mode.

“Because I've got you,” their mother said as she reached down and pulled Oliver up onto the ledge next to her. He didn't resist. If felt good to be with his mom.

“Come on, Celia,” he said. “I'll go first. Like always.”

They heard the clanking of boots coming toward them. Doors burst open. Nuns screamed and clapped. The sound was getting closer.

“Fine,” Celia said, and let her mother help her up to the ledge. “But you carry the backpack.” Their mother agreed and took it, not even asking what was inside.

They stepped out onto the ledge and knocked the window shut behind them, slipping to the side just as the door burst open.

“No one here,” Sir Edmund shouted, looking into the room. “Next.” He and the guards continued on, while Celia and Oliver pressed their backs hard against the outside wall. The ledge was slippery and every time their weight shifted, they slipped a little bit. The wind pushed at them like a bulldozer and their mother put her hands across their chests, helping them stay back. Down below them on the ground was a large cage with a heavy wooden door that led back into the monastery. In it, exposed to all the wind and the cold, a yeti paced back and forth. It looked right up at Oliver and Celia and roared.

“A yeti!” Oliver yelped, remembering his last encounter all too well. This one was smaller than the one that had attacked him, but still looked ferocious.

“It's just a baby,” Dr. Navel explained. “They brought it here a few days ago. It hasn't stopped pacing since they took its mother away.” She grew quiet for a moment. “Okay, stay close to the wall,” she said at last, changing the subject. “Put your feet down carefully in front of you. Don't shift your weight onto a foot until you've set it firmly. You don't want to slip on the ice. We're just going around the corner ahead of us. Fifteen feet. That's all.”

Their mother was going first. Oliver held her belt with one hand and used the other one for balance. Celia held on to him the same way. And they started forward together without another word. It was the longest fifteen feet of their lives. If they survived it, Celia thought, their mother had a lot of questions to answer: three years, a yak and an airplane's worth of questions.

Other books

The Poison Sky by John Shannon

Remedy is None by William McIlvanney

The Hollywood Mission by Deborah Abela

Stay With Me by Maya Banks

A Boulder Creek Christmas by Mary Manners

Spurious by Lars Iyer

Murder Bone by Bone by Lora Roberts

Powerful Men 2: Four More Alphas Who Seize Control by Kane, Carla

Prelude for a Lord by Camille Elliot