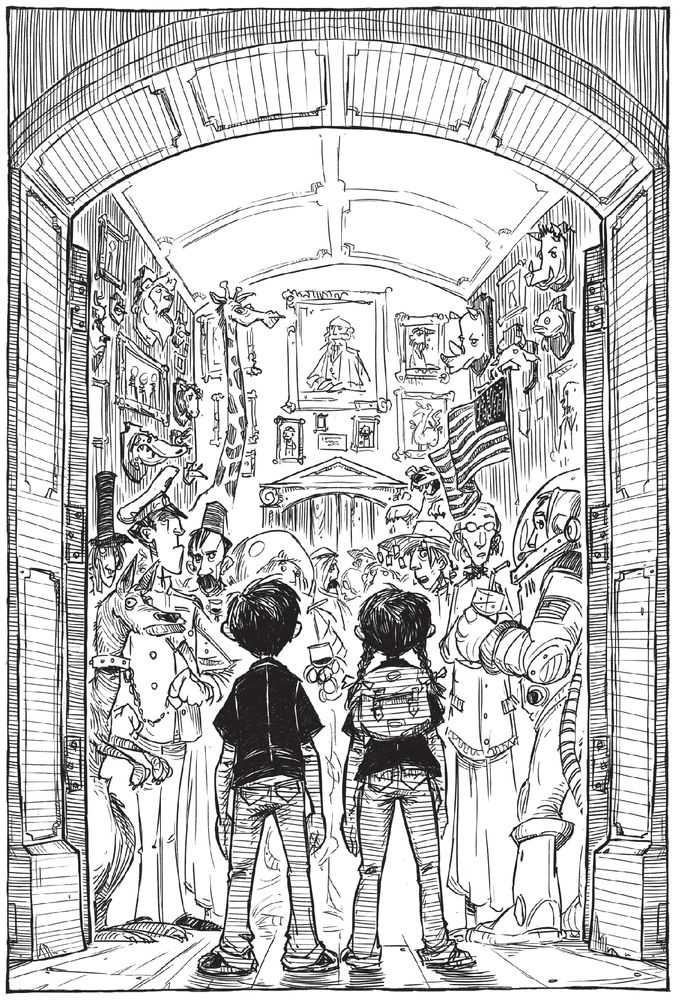

We Are Not Eaten by Yaks (5 page)

Read We Are Not Eaten by Yaks Online

Authors: C. Alexander London

“. . . and there was the Great Oracle, the ferocious spirit of Dorjee Drakden, eternal protector of the Tibetan people, waving his sword over his head like an ancient Tibetan warrior,” she said. This was the mountain climber their father had been so excited to meet.

“Dad,” Celia whispered, tugging at her father's tuxedo jacket.

“Shhh.” He swatted her hand away. She tugged again. He swatted her again and gave her one of those looks that parents must learn from some book. She let go of his tuxedo.

“What do we do?” mouthed Oliver to his sister, trying not to attract too much attention. Celia scratched her head while she thought and raised a small cloud of dust.

“The oracle growled and hissed.” The mountain climber was still telling her story. “His spirit was wearing the body of a little monk like a costume, making him do things that would have been impossible for a person to do if he weren't possessed by the Oracle. His robes twirled, and his sword whistled through the air and stopped a hair's width from my throat!”

She spun and slashed her hands through the air like a sword as she spoke. She winked at Celia, who stared back at her with an expression on her face like she'd just seen an infomercial for hedge clippers. Choden Thordup continued.

“The oracle demanded I prove my courage. He demanded that I jump out the window. We were in a monastery high on the edge of the Tsangpo Gorge, which fell ten thousand feet below us.” She paused and let the terror of her situation sink in.

Celia crossed her arms, waiting for the explorer to keep talking. Oliver rolled his eyes. There was nothing dramatic about pauses, he thought. They were like commercial breaks and he wondered why storytellers always insisted on using them. Why didn't she just get to the point? They had to warn their father already.

Oliver decided to interrupt: “Dad, we have to tell you something.”

“Not now, Oliver,” Dr. Navel said. “What's gotten in to you both? Ms. Thordup is telling a story.”

“But it's important!”

“It will have to wait a moment. It is rude to interrupt. I don't interrupt you when you are watching your stories on television.”

“Yes you do!” Oliver objected. “All the time!”

“Well, I'm your father and I'm allowed. Now, let Ms. Thordup finish her tale.” He turned to the mountain climber. “Apologies. Please, continue.”

Oliver shifted from foot to foot while Choden continued.

“The fall would certainly kill me,” she said. “Then again, the sword at my throat would certainly kill me too. We needed the oracle's blessing to continue our journey, so I did what any reasonable explorer would have done. I smiled and then flung myself out the window.”

Dr. Navel looked at his son and raised his eyebrows, trying to show how impressive it all was, but Oliver just stared back with the same expression a cow might have, had it been invited to a Ceremony of Discovery at the Explorers Club.

He was wondering if it was worth enduring the rest of this story to warn their father. Maybe they should have run away, if this was how they were to be treated when they had important news. Celia crossed her arms and tapped her foot impatiently. Sir Edmund was probably somewhere in the crowd putting his plans into motion and their father cared more about some mountain climber falling out a window. Celia felt that this was a deep injustice. Missing TV, finding out devious plots, and now, listening to long stories about Tibet! On TV, warnings were given much faster. No one ever had to listen to speeches on

Love at 30,000 Feet

unless they were really important.

Love at 30,000 Feet

unless they were really important.

“Dad, there's a plot to destroyâ” Celia tried to say, but the mountain climber just kept talking over her.

“I landed on a wild yak, sixty feet below,” Choden continued, ignoring the twins. Their father's face was growing red with anger while he tried to act like he also hadn't noticed his children's outbursts. “Yaks are amazingly strong creatures and their thick fur makes for a soft landing. I rode the yak back up to the monastery, where the oracle was laughing hysterically. He told me that the yak was his gift to me. He then left the body of the monk he had possessed, who collapsed, rigid, to the floor. We named the yak Stephen, and I later donated him to the Denver Zoo.”

The men laughed. The children did not, even though it is hard to keep a straight face when someone says the word

yak

over and over again.

yak

over and over again.

“I don't believe I've had the pleasure of meeting you yet,” the climber said, finally turning to Oliver and Celia. “What are your names?”

“Celia,” said Celia.

“And Oliver,” said Oliver.

“My name is Choden Thordup,” said Choden Thordup, pointing to her name tag. “As you probably guessed, I'm a mountain climber. Are you interested in mountains?”

“No,” Celia answered for both of them.

“We're not,” Oliver added for both of them too. He didn't like that his sister always tried to get in the last word. And the first word, for that matter.

“You must be undersea explorers then.” Choden smiled.

“Nope.”

“Astronauts?” she tried, still smiling.

“No.”

“Jungle trekkers?”

“No.”

“Egyptologists? Botanists? Geographers?”

“We don't like to go anywhere,” Celia said.

“Or do anything,” Oliver added.

Choden Thordup's smile vanished, as did Dr. Navel's.

“Well, I see, umm . . . ,” Choden said after a long and uncomfortable pause. The children just stared at her. Her face turned red.

“Can we talk to our father now?” Celia snapped. “It's a little more important than yaks.”

“Well,” Choden said, and smiled too nicely. “I have to tell your father something too, so why don't you just wait a pretty little minute? Young people in my country are

never

allowed to interrupt adults. They must learn patience.”

never

allowed to interrupt adults. They must learn patience.”

Explorers are a special kind of adult, like magicians and clowns, who hate it when children don't find them fascinating. This one, it appeared, got very mean.

Celia did not like Choden Thordup, and neither did Oliver. Their father was shooting daggers at them with his eyes. Oliver and Celia couldn't believe it. They were trying to save his life and he thought they were being rude!

“Dr. Navel.” Choden turned to him. “After leaving the monastery, I descended to the rapid river in the gorge below. The gorge is one of the last unexplored regions on earth. No one knows who or

what

lives down there. I hoped I might find Shangri-La in its depths.”

what

lives down there. I hoped I might find Shangri-La in its depths.”

“Shangri-La!” exclaimed Professor Eckhart. “Such a place is only a legend.”

“Perhaps,” said the mountain climber. “But in my travels, I stumbled upon the remains of a temple behind a giant waterfall. The building, built inside a cave, had been burned, but in the ruins, I found this.”

She pulled a clear plastic folder from under her dress. In it was a piece of parchment that looked very old. It was covered with symbols and strange writing. The writing looked a lot like the weird writing from the walls of the tunnel behind the bookcase in Oliver and Celia's apartment. The edges of the parchment were black where the fire had touched them.

“I believe this is a piece ofâ”

“The Lost Tablets of Alexandria!” Dr. Navel interrupted, gasping, and no longer looking at his children. Suddenly, the room went silent and all heads turned toward him. “From the Lost Library itself.”

“And there's another thing,” said Choden Thordup, turning the document over to reveal the back. It was covered in small, neat letters, written in light blue ink.

When he saw it, Dr. Navel gasped and dropped his sherry glass to the floor, where it shattered.

6

WE WITNESS A WAGER

DR. NAVEL TOOK

the plastic folder from the mountain climber and studied it carefully, as the whole room got quiet.

the plastic folder from the mountain climber and studied it carefully, as the whole room got quiet.

“This is my

wife's

handwriting,” he said. Oliver and Celia looked at each other, stunned. For a second, they forgot all about the plot to destroy their father.

wife's

handwriting,” he said. Oliver and Celia looked at each other, stunned. For a second, they forgot all about the plot to destroy their father.

“I do not know the language on the paper,” explained Choden Thordup. “But the image at the top of the page is clearly the seal of Alexander the Great. Your wife, thankfully, wrote in English on the back.”

“Mom?” Oliver mouthed at Celia, who just shook her head with confusion. They had both seen their father get excited about clues before. He'd dragged them all over the world looking for their mother, and it never led to anything but long flights, animal attacks, missed television, lizard bites and disappointment. Celia just couldn't get too excited about some old piece of paper. And Oliver got his hopes up way too easily. Sometimes Celia felt like she was three years older than her brother, rather than three minutes and forty-two seconds.

“The language is ancient Greek,” Dr. Navel pointed out, and Celia managed to see strange letters and weird symbols curling around each other.

For years, she'd heard her father say the phrase “it's all Greek to me” when he didn't understand something, and now she knew what he meant. The symbols didn't look like any letters Celia knew. She couldn't understand them at all.

“âMega biblion, mega kakon,'”

Dr. Navel read out loud.

Dr. Navel read out loud.

Ancient Greek, we should note, wasn't “all Greek” to Dr. Navel. He understood it perfectly, as any decent explorer would.

“Big books, big evil!” said Dr. Navel. “A statement by the famous Callimachus.”

“Who is Callimachus?” Oliver asked, and his sister glared at him. Her brother was already distracted from the point of coming to the ceremonyâto warn their father and to get cable.

“He was a scholar at the Library of Alexandria,” Dr. Navel said. “He invented the first classification system in the world. He organized all the knowledge in the libraryâwhich was written on these tablets. The Lost Tablets are the catalog of the Great Libraryâa complete account of all its wonders. They were created back before the library was lost.”

“That doesn't look like a tablet,” Oliver said.

“Well, they called them tablets,” Dr. Navel answered, “but they really used parchment to write them. It wouldn't have been practical to carve new tablets for every book and scroll. The library was far too big. It held all the knowledge in the world.”

“Ugh,” Celia groaned. “We have to hear about librarians now? This is worse than school! Worse than afternoon public television! Dad, we have to warn you aboutâ”

“Callimachus had a feud with the other scholars in Alexandria,” Dr. Navel continued, thinking out loud and not hearing a word his daughter was trying to say. “Some said he was part of a secret society that was trying to take over the library and seal it off from the world, but no proof has ever been found.”

“Why was he a librarian if he thought big books were evil? Why would he want to seal it off?” Oliver wondered, and then saw his sister glaring at him again. “You know, as if I cared,” he added.

“That is an excellent question,” Dr. Navel said, thrilled his son was taking an interest. Their mother always said that their father had “selective hearing.” Celia never knew what that meant until now. “Callimachus was from the noble class, and he hated the idea of common people having access to all that knowledge. Knowledge is power, after all, and all the knowledge in the world would mean all the power in the world. Callimachus thought that that power should be kept for only a fewâ”

“Dad,” Celia interrupted, because she just didn't care about ancient librarians. “We have to warn you aboutâ”

“Look at what your wife says,” Choden Thordup interrupted Celia, who was getting really sick of being ignored.

Other books

Blood Loss: The Chronicle of Rael by Martin Parece, Mary Parece, Philip Jarvis

The Trees by Conrad Richter

The Memory Agent & Fool Me Once by Kane, Joany

Created Darkly by Gena D. Lutz

The Post-Birthday World by Lionel Shriver

Voices by Ursula K. Le Guin

Diggers by Viktors Duks

The Spirit House by William Sleator

Self-Made Man by Norah Vincent

The Catswold Portal by Shirley Rousseau Murphy