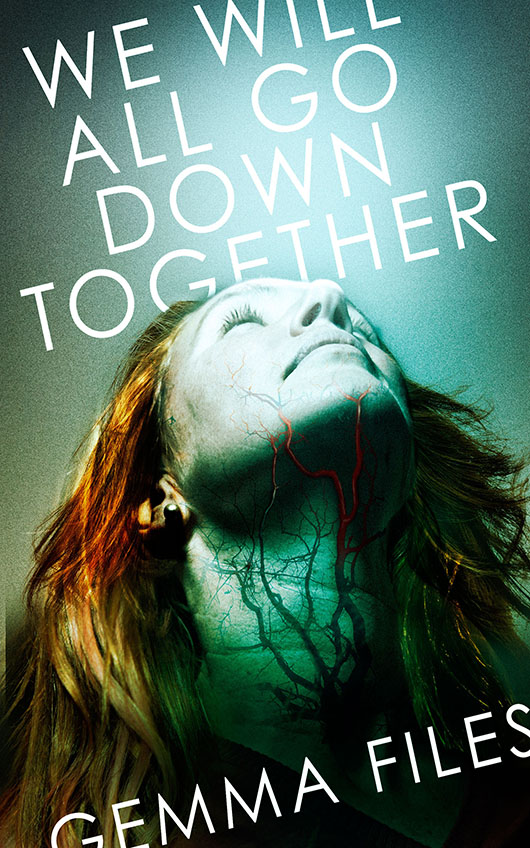

We Will All Go Down Together

Read We Will All Go Down Together Online

Authors: Gemma Files

FIVE-FAMILY COVEN

GEMMA FILES

ChiZine Publications

GEMMA FILES

“Potent mythology, complex characters, and dollops of creeping horror and baroque gore establish Files’s Hexslinger series as a top-notch horror-fantasy saga.”

—Publishers Weekly

A Tree of Bones

has . . . plenty of spectacle and action to keep the plot moving. I highly recommend the series as a whole, it provides a refreshingly different variety of fantasy.”

—SFRevu

“[

A Rope of Thorns

] paints a stark, vivid, and gory picture of the ‘wild west’ in the years following the Civil War. . . . Filled with antiheroes, sacrificial victims, and supernatural beings, Files’s latest is not for the squeamish but should delight fans of gothic Western fantasy and Central American myths.”

—Library Journal

“For all that it is character driven, [the Hexslinger Trilogy] is full of sound and fury, as gods and magicians go head to head in epic battles that transmute the warp and weft of reality itself. Files commits to the page scenes so vivid that they will brand themselves on the reader’s mind . . . She has produced a luminous and uncompromising fantasy series, one that is awash in blood and shot through with remorseless brutality, but also peppered with scenes of striking originality, a narrative that should appeal to horror fans and all those who adore anything that is different. Succinctly, I loved it from first word to last.”

—Black Static

Where have you been, my long-lost love, these seven long years and more?

—“The Demon Lover,” traditional ballad

You must not go to the wood at night.

—Henry Treece

The Five: A Warning to the Curious

Landscape with Maps & Legends: Dead Voices on Air (2004)

Words Written Backwards (2003)

Heart’s Hole (Time, the Revelator Remix) (2005)

Amanda Downum

When I first read Gemma’s novel

A Book of Tongues

, I said that it “

lays eggs in your brain, and when the eggs hatch your skull splits open and a thousand shiny green scorpions and spiders swarm out of your eye sockets, and when they’ve eaten the last of your brains, a spider spins a web in the hollowed-out curve of your skull, and the web reads ‘

Some book.’

In Nahuatl.”

I was, unsurprisingly, quite delighted to read

We Will All Go Down Together

.

As much as I love scorpions, spiders, and Aztec gods, witches and angels and fae are even more deeply imprinted on my reading DNA. Since I was old enough to wander the horror and fantasy aisles in bookstores, these have been the stories to which I’ve gravitated. And while witches and angels and the fair folk are easy to find in bookstores, rarely do I find them depicted in ways so close to my heart.

The witches and fae who populate Files’ haunted Toronto aren’t sexy or sanitized. These witches deal in blood and souls and devils’ bargains; these fae trade in lives and steal away hapless mortals—not to fairy-tale forests and shining castles, but to the darkness and damp of hollow hills filled with bones and rot. Instead of eternal youth and Hollywood cheekbones, Files offers us the slimy, squelching vision of what it might really be like to transform into a hungry creature of rivers and marshes. She gives us not just the threat of

twa e’en o’ a tree

, but oozing flesh worn raw by wood.

We Will All Go Down Together

is built on combinations and contrasts. Individual short stories and novellas combine to illuminate characters as well as the overarching plot. The historical horrors of Jacobean witch hunts combine with New Age spiritualism, Scottish and Chinese and First Nations folklore with biblical apocrypha. The characters are driven by rage and pain and pride, by love and duty, faith and pragmatism. The stories are simultaneously cruel and sweet, brutal and hopeful, raw and bruising and so sharp you don’t feel the wound till you’ve reached the end. They balance tropes of the fantastic with unnerving grotesquerie—urban fantasy’s sense of being one step away from the magical and numinous, and horror’s creeping violation of the seemingly familiar. Like Files’ monsters—the best sort of monsters—they’re beautiful, enticing, sharp-toothed, and skin-crawlingly creepy.

This is not a book for the faint of heart, but read it anyway. Maybe you’re stronger than you realize.

A Warning to the Curious

Gemma Files

Every story is made of stories, and all of those collected here trace back to one begun long before, in another country, another century. It tells of how five people, each of whom represented part of the same cursed lineage—the bastard seed of a thousand evil angels, thrown down on rocky soil and left to grow unchecked, breeding a secret poisoned treasure of supernatural power in its unlucky inheritors—met for fell purposes, swearing together to carry out a great and secret work which would rock the very world to its core. Branded as monsters and persecuted by those who considered them impure, damned, contaminating, they allied together only to split each from each along lines carved by privilege, for two of them were noble, three not. And so the fated break ensued, inevitably: when betrayal struck, the rich and moneyed escaped “justice,” or King and Church’s notion of it, while the poor and low suffered its full extent.

Yet no one who tells this first tale debates whether or not all its protagonists deserved equally to die for what they did, or planned to do, in their way . . . all are considered equally guilty, even by the surviving descendants of these fabled five, carriers of their bad blood and worse history alike. And so it remains a legend strange things tell each other, a bedtime fable recited by monsters, to monsters; its long shadow falls over all subsequent stories, staining them in shades of pitch-black smoke and hellish flame, lending them a stench of blown ash and bone-grit. While always those who begin it do so with these same words, unfailingly—

Listen now, my darling; lean closer still, and I will speak in hushed voice of the Five-Family Coven, who dared all only to lose all, whose infamous names will surely live forever. They of the line of Glouwer, of Devize, of Rusk, witches and witch-children, of whom none are spared. They who bear either the name Druir or that of Sidderstane, who dwell forever trapped in Dourvale’s twilight, outcast from two worlds and citizens of none. They who once held the title of Roke, wizards and warlocks of high renown, who bent the elements to their will and learned the names of every creature more awful than themselves, if only so that they might bend them to their will.

Here is where things start, always—the bone beneath the stone, the great tap-root. The hole which goes down and down. That old, cold shadow, always waxing, never waning. That taste, so bitter in the back of your mouth, which almost seems to echo the tang of your own blood.

Perhaps you recognize their names, now—catch in their descriptions just the faintest possible echo of someone you suspect, someone you yearn towards without knowing why, someone you love yet fear, or fear to love. Of yourself, even. And perhaps this resonance, like some tiny bell’s distant toll, makes you suddenly wish to know more.

Well, then: you are in luck, of a kind, for here you hold a book which can answer all relevant questions if only asked properly, just waiting for your touch upon its covers. Do so, therefore; open it to you, yourself to it. Breathe deep the dust of its pages, scrape some ink, take samples of its pulp. Or simply plunge in unprepared, risking nothing but your own ignorance . . . a hazard surely easy enough to gamble without much caution, even without knowing what else might really be at stake. . . .

. . . and see what happens next.

DEAD VOICES ON AIR (2004)

The following extracts were recovered by forensic Internet technicians from Galit Michaels’ deleted Folksinger.net blog of the same name, at the request of her relatives.

August 10, 2004

Mood: Ebullient

Music: “Wayfaring Stranger,” Johnny Cash

Title: Don’t Drink and Post

Like opening the bible at random, songwriting can be a form of bibliomancy—logomancy, rather. Words come out of nowhere, sometimes—out of sequence, out of sync. Rhymes optional. Phrases misheard, misshapen, reshapened, lost in translation and all the better for it: done to death, done deathly, O maid too soon taken. . . .

O whither shall I wander

With white horn soft blowing

Down dark rivers walking

Down dark halls gone flowing. . . .

There’s something there, or could be. Look at it again in the morning, when you’re not so drunk.

August 12, 2004

Mood: Blah

Music: “On the Bank of Red Roses,” June Tabor

Title: Beer Bad, Head Slow

Ugh. Two days later, and I can still feel that freakin’ sickly sweet Raspberry Wheat concoction of Josh’s in the back of my throat, a technicolour yawn waiting to happen. Tonight’s show has us back at Renaissance West rather than East, but that’s about all that’s changed. Sometimes I feel like we’re on some sort of endless loop, just shuttling back and forth between two clubs with the same name, always performing to the same bunch of people, give or take: wannabe slam poets, Society for Creative Anachronism rejects, girl-with-guitar music fetishists (and I say that as the girl).

During rehearsal, Josh and Lars kept sniping at each other—Lars picked a fight about material, started in on this rant about how we were doing too many “stupid-ass murder ballads,” how all folk songs are derivative and repetitious, etc. Why don’t we write our own stuff in a similar vein, like Nick Cave with “Where the Wild Roses Grow”? Pointed out that “Wild Roses” is basically “On the Bank of Red Roses” redux, tricked out with a little Nietzschean posturing and Kylie Minogue as the ghost, but he didn’t wanna hear it; Josh got sidetracked somehow onto whether or not “Delia’s Gone” is too po-mo to be misogynist, and I went home early. They barely seemed to notice.

Stepping out onto Church Street, I ran straight into what looked like a truly weird combination of frost and condensation happening at apparently the same time—freezing rain, rising haze, glistening windows, cars, trees. My glasses turned everything I passed pointilescent, including this older guy paused just on the corner, skimming through today’s

Dose

. He had some kind of severe Scots accent (Highlands? Lowlands? Midlands? . . . no, that’s British, isn’t it?), so thick I had to pause and double-take for a minute when he suddenly said:

“You’re the singer, yeah? From Gaucho Joe’s.”

“I sing there sometimes, yes.”

“Liked what you did with ‘Tam Lin,’ last time.”

“Um, thanks.” And after a sec, ’cause I never can seem to stop myself: “What part?”

And now he was looking at

me

, over the paper’s sodden rim—not that “old” at all, really, not even middle-aged. Maybe almost my age, even. But he did have that reddish-grey hair and eyes to match, from what I could make out through the fog on my lenses; something sort of stylish-tough and vaguely familiar about him too, like he looked like one of the sidekick actors from

Gangster Number One

, or whatever.

Then he smiles, teeth hella-bad like every U.K. dude, and goes: “The whole of it, hen. The song itself—it’s so

true

, and that’s so bloody hard to come by, yeah. Don’t you think?”

“I guess. . . .”

And . . . that was about it, basically. Super-weird, even for a Monday. Weird on

top

of weird, squared and triple-squared, to the infinite power.

Now I need water and TV time, and to get myself together. And sleep too, because tomorrow’s Tuesday, and there’s work.

Not to mention laundry.

August 15, 2004

Mood: Pensive/thinky

Music: That creepy hissing noise inside my head

Title: “True”?

Crap day at The Grind, as ever. I’m getting that “you just don’t mesh with the Coffee Crossroads program, Galit” vibe pretty hard off of Daphinis these days, like basically the whole time I’m there—doesn’t make a double shift go by any faster, that’s for damn sure. So I guess that spending a sizeable chunk of time checking the Classifieds might be in order, as of this weekend: fuck it, suits me. Never stay too long anywhere they make you wear a uniform jacket they’re obviously too cheap to dry-clean on a regular basis, that’s

my

motto.

But yeah, I do keep sort of thinking about what that guy said, and that probably has me distracted enough to show. Because . . . well, “true”? “Tam Lin” is a

fairy tale

, for Christ’s sake. It doesn’t even have the tabloid oomph of something like “Pretty Saro” or “Sam Hall” (damn your eyes!) to back it up. Just Fair Janet pulling the roses and then this “fair and full o’ flesh” dude suddenly ’fessing to knocking her up, plus the whole thing with the Fairy Queen and her looming tithe to Hell—the bad flipside of “Stolen Child,” in other words, with Tam Lin himself the changeling boy looking ’round years later and deciding he really does prefer his former human world after all, “full of weeping” though it may well still be. After which she breaks the spell, so the Fairy Queen goes all totally off on her with that spooky revenge-threat rant—

A curse on you, Fair Janet,

And an ill death may you dee!

If ever I’d known you’d stray, Tam Lin,

And look on ought but me,

I would ha’ ta’en out thy twa grey een

And put in twa een o’ tree.

Wooden eyes, like that guy from

Pirates of the Caribbean

; man, you know

that’d

grate whenever you blinked. Splinter, too.

Anyhow. Back to Joe’s tomorrow, interestingly enough: Scottish Richard Gere-guy territory! I know the guys really want to do “Tam” again too, mainly because Lars thought Josh fucked up his solo; this testosterone crap really does have to stop, or . . . well. More job-shopping, just from a different angle.

Funny thing about that dude, actually—might have been the fog or whatever, but I’m having a serious bitch of a time even halfway remembering what he looked like. So much so that I wonder if I’ll be able to spot him in the audience, if he does come.

August 20, 2004

Mood: Energized

Music: “Raise the Dead”, Linda Ronstadt and Emmylou Harris

Title: Well, It Finally Happened . . .

. . . and Glamer is now very much a thing of the past, at least the version of it incorporating Mister and Mister Let’s-Whip-Out-Our-Dicks-and-Joust. The whole process was surprisingly painless, at least where Lars is concerned: “Never liked this fag outfit anyhow,” huh huh huh huh. “You mean fag-and-

dyke

outfit?” I yelled, as he walked away, and Josh thought that was pretty damn funny, right up until the point where I gave him

his

marching orders, too.

“Come

on

, Galit—don’t we work well together? Be fair, man.”

“It’s not about me working with you, Josh, it’s about you working with anybody else.”

“What, like Lars? Buddy just loves to rumble, generally; check out his act in a week or two, he’ll probably be smashing up his

own

guitars.”

To which I thought:

Yeah, well, possibly. But it does take two to tango, and I sure as hell don’t ever remember really being part of that dance—that was all you, all

over

me. And I don’t think that was only just with Lars, either.

Because if we were honest, then we’d admit the unspoken fact that our lack of actual “together-ness” has always been the engine driving Josh-and-I’s creative truck, pretty much since we first got . . . uh . . . together. And that used to work fine, back when there was only the two of us—before Kathy, or Oona, or what’s-her-name on his side, before Sean, or Drew, or (for that matter, though only one drunken time, thank Christ) Lars himself on mine—but these days, it just doesn’t seem to be working anymore. There’s too much drama, too much sublimated jealousy; the music suffers.

I

suffer. The investment isn’t worth the return, and blah blah blabbitty blah, ad infinitum.

So now, it’s back to the old faithful formative one-chick acoustic version of Glamer for a while, until I can spare the time to hold auditions. As in any good divorce, we tallied stuff up and split it down the middle: I get to keep the band’s name, he gets to keep all his arrangements, we both get to keep our own instruments, here endeth the lesson; everybody walks away content, hopefully, if not particularly happy. I promised to buy him a beer the next time our paths crossed, kissed him on the cheek, and booked.

Wasn’t until I was already on the subway home that it finally hit me, though—one of the songs I’d just given away was “Tam Lin,” and I never did see that dude at our last show as an intact musical entity. Shit.

All the more reason to find myself a brand “new” old song to push, though, isn’t it? One that everybody and their sibling

don’t

already know inside-out and backwards. One that’s just for me. ;)

Comments:

Have you tried looking through the Connaught Trust’s balladry collection? Their Reading Room is open to the public from noon to midnight on every day but Sunday.

—Posted by:

[email protected]

Seriously? I don’t think I’ve ever heard of it.

—Posted by:

[email protected]

It’s a private endowment, co-administrated by the Connaught family’s law firm and a subdivision of the Toronto Catholic Archdiocese. Really good for research, especially when it involves obscure folklore. The “Ontario ballads” were added around 1976, after the guy who compiled them’s last surviving heir finally died, and she willed them to the Trust. You’ll find the address in the White Pages.

—Posted by:

[email protected]

Thanks! I’ll check it out.

—Posted by:

[email protected]

August 22, 2004

Mood: Undecided

Music: “Priests,” Judy Collins

Title: A Trip to the Connaught

Okay, so that was . . .

You know, at this point, I don’t even really know. Offputting? To say the least.

The place turned out to be on one of those weird little streets off the U of T stretch on St. George, which I’m obviously not all that familiar with to begin with, since I went to Ryerson. There’s the library, a big glass-fronted 1960s monolith, apparently hanging out of the sky at a truly scary angle—sort of reminds me of those cubist spaceships you’d always see on the front of U.K. science-fiction paperbacks in the early 1980s, by guys like Brian Aldiss or John Wyndham. And next to that, on either side, you’ve got the basic student services sprawl: converted town houses occupied by frats and (sorts?), crap-ass residential apartment complexes, cheap pubs, cheaper Indian and Canadian-Chinese cafeteria-style “restaurants,” the inevitable Second Cups.

Plus, everywhere else you look, you’re already turning down another of these street-sign-less cul-de-sacs lined with increasingly threatening trees: maples, oaks, lilacs, all overgrown, pavement underneath covered in a muck of dead leaves. Seriously, was there some sort of post-Dutch Elm disease mass-replanting program nobody ever told me about in school? Because it’s kind of like Mutual of Omaha’s

Wild Kingdom

in there, these days; go too far down one of these suckers, I’m surprised anyone ever finds their way back out.

The fabled Connaught Trust, meanwhile, turns out to be a relatively big, weather-worn house completely shrouded in a tangle of pines so thick I could see what looked like four years’ growth of spiderwebs turning the sun grey whenever I looked up (which I only did the once, for obvious reasons). Cones and half-cones were piled everywhere along the path, crunching queasily underfoot like they’d just been left to lie there and marinate. If I hadn’t finally spotted the plaque on the front door, I’d’ve been out of there in about 2.5 seconds; unfortunately for me, though, I did. And I sort of thought I could see somebody in there too, looking out at me through one of the second-floor windows. . . .

So I knocked: nothing. Pushed on the door, which gave in, slowly. The place smelled like Pine-Sol and dust, though you wouldn’t necessarily think that was possible. A Magritte print on the wall, above a row of hooks for coats: that one with the wooden picture-frame full of red brick hung against dove-grey wallpaper, above olive-drab panelling. And maybe it was just a trick of the lack of light, but that paper looked almost exactly the same shade as the paper inside the Trust’s hall, with the panelling underneath it pretty much the same shade, too. . . .

Stood there and stared at it for a minute or two, more than a bit freaked out, hearing the pines creak behind me, afraid my collar wasn’t quite up far enough to spiderproof me completely. Until, thank Christ, somebody finally came downstairs—this completely normal lady, albeit just a little bit butch, with her hair back in a French braid and a very subtle gold cross pinned on her collar; the Church contingent, I can only assume, since I didn’t have either the wherewithal or the guts to ask her outright if she was a nun, or what.

“I’m looking for the Ontario Ballads?”

“You mean Torrance Sidderstane’s collection,” she said.

“Um, maybe.”

She nodded slightly, like I’d proved her point for her, and glanced back up. Said: “Second Floor, third door in. Ask for Sister Apollonia.”

Okay, anyway—I’ve already gone waaay too far in terms of setting the scene, which is why I’m going to skip right to the good part. Turns out, this Sidderstane guy was trying to put together Canada’s own version of the Childe Ballads; went back and forth throughout Ontario and parts of Quebec for most of his life, taking down oral history and transcribing songs, starting right after the Boer War and going straight through World War One, up until he finally died of flu during the 1918 pandemic. And a lot of it’s the same sort of stuff you’d find in most other places, with all the doubling and crossover you usually get with Folk: I mean, we all know how all you have to do is Americanize something slightly, slide from Steeleye Span to Leadbelly/Nirvana, and suddenly “The Gorse and the Heath” becomes “In the Pines,” like a Sherlock Holmes locked-room mystery morphing into the Green River Killer’s A&E TV biopic—