Weird Tales volume 31 number 03 (6 page)

Read Weird Tales volume 31 number 03 Online

Authors: 1888â1940 Farnsworth Wright

Tags: #pulp; pulps; pulp magazine; horror; fantasy; weird fiction; weird tales

2, The Spider and the Flies

" and the man is a perfect ghoul

about money. You know most of the people here, Mary; you wouldn't say that any were really poor, would you?"

Mary Roberts looked about this room in which she sat. It was a long room, extending the full length of *:he second floor of a brownstone, solidly aristocratic house; obviously two interior walls had been demolished to provide the single large chamber. The wall to Mary's left, abutting the adjoining house, was blank; red velvet drapes covered the windows

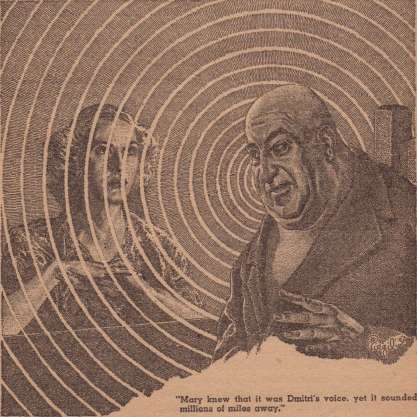

"Mary knew that it was Dmitri's voice, yet it sounded millions oi miles away."

WEIRD TALES

at the ends of the room. Three doors, irregularly spaced along the right-hand wall, led into the second-floor corridor. A ponderous oaken table and chair stood dose to the drapes at one end of the room; about sixty folding-chairs were arranged in orderly rows facing these grimly utilitarian furnishings. Perhaps thirty persons, the great majority of whom were women, sat in small, self-conscious groups about the room, talking among themselves in low tones. Occasionally someone laughed — nervous laughter that was quickly suppressed.

Dmitri's evenings, Mary Roberts suspected, were not particularly pleasant affairs. . . .

Mary knew these people. One or two were really ill, several were suffering from neuroses, a few were crackpot faddists, but the majority were merely out for a thrill. And all were wealthy.

The man Dmitri, Mary decided as she looked about, must be, even if a charlatan, certainly a personality. . . .

She turned, with a wry smile, to her friend.

"This gathering surely makes me feel like a poor little church-mouse," she admitted ruefully. "Father was never a financial giant, you know, Helen."

Helen Stacey-Forbes smiled reassuringly.

"Money can't buy character and breeding, my dear. I see old Mortimer Dunlop up there in the second row; you are welcome in homes he's never seen and never will see—except from the street. Damned old bucket-shop pirate! Have you heard the rumor that he's full of carcinoma? They're giving him from six to nine months to live. That must be why he's here; someone's told him about Dmitri "

Mary gasped. "And people believe that Dmitri can cure carcinoma? Why, it's—Charles said only the other day that Dmitri was merely a half-cracked psychia-

trist who's had rather spectacular luck with a few rich patients' imaginary ailments. But carcinoma !"

Gravely Helen Stacey-Forbes shook her head. "Dmitri's far greater than his enemies will admit. They call him a super-psychologist, a faith-healer, and they laugh at him and threaten him, but the fact remains that his methods succeed. He achieves cures, impossible cures, miraculous cures. I know, because he's the only man who can stop Ronny's hemorrhages. At five thousand dollars a treatment."

"Five thousand dollars!"

Helen laughed, a dry, bitter little laugh. "Believe me, Dmitri is a monster, not a man. Mortimer Dunlop will have to pay dearly for his carcinoma cure!"

The words sent an odd little shudder racing along Mary's spine. For, obviously, Helen Stacey-Forbes believed, believed implicitly, that Dmitri could cure—cancer!

Suddenly, men, the room was silent. The door at the upper end of the chamber had opened, a man had entered.

IN the abrupt stillness the man, small, self-effacing, bearing in his hands a large lacquered tray, walked to the oaken table and arranged upon it several articles —a half-dollar, a pair of pliers, a penny box of matches, a small-caliber automatic pistol, a ten-ounce drinking-glass, a tinkling pitcher of ice-water, and a battered gasoline blow-torch. A curious, incomprehensible array. . . ,

The little man left the room. The babble of nervous voices began again, as suddenly stopped when the door reopened and a monstrosity entered.

The man was huge. At least six feet three inches tall, he was as tremendous horizontally as vertically. A mountain of flesh swathed in a silken lounging-robe, he slowly walked to the table, and settled, grunting, into the big oaken chair. In-

THE THING ON THE FLOOR

283

stantly immobile, he surveyed the room through small, coal-black eyes set close together in a pasty-white face. Obscene of body and countenance, his forehead was nevertheless magnificent, but his scalp, even to the sides of his head, was utterly bald. Beneath the table his pillarlike ankles showed whitely above Gargantuan house-slippers.

This— this, Mary Roberts knew, was Dmitri. . . .

Leisurely the monster poured a glass of water and took a tentative sip, the glass looking no larger than a jigger in his tremendous, flabby hand. An expression that might have been a smile—or a leer —rippled momentarily across his fat-engulfed features, revealed an instant's glimpse of startlingly white teeth. He began to speak

"I see a number of new faces before me today," he began in a voice incongruously, almost shockingly vibrant and beautiful; Enrico Caruso's speaking voice, Mary thought suddenly, must have sounded like that—"and for the benefit of those who are not already familiar with my theories I will repeat, briefly, my conception of the function of the Will in the treatment of disease."

He paused, sipped meagerly from his glass of ice-water. Then he went on, his speech only faintly stilted, only faintly revealing him a man to whom English was an acquired language:

"Speaking in the philosophical—not the chemical—sense, it is my belief that there is but one fundamental element-abstract mind. Of course, that which we term matter is, in the last analysis, energy; there is no such thing as matter except as a manifestation of energy. Yet it is quite obvious, or it should be obvious, at any rate, that mind—that attribute which we wrongfully confuse with consciousness^—is totally independent of matter. A man dies, but his atomic weight remains

unchanged; the strange force which activated him has found its material shell no longer tenable, and has taken its departure.

"We are all well acquainted with the axiomatic law of physics which deals with the conservation of energy. But here we reach a paradox—either energy must have been non-existent at one time, or it must be eternal—contradictory and utterly irreconcilable concepts. The logical and the only conclusion is plain: energy and matter do not and have never existed. They are but temporary conceptions of an infinite, timeless Mind, a Mind of which we are part "

There was a sudden snort from the second row, "Rubbish! What's all this jabber got to do with me? I came here to be cured, not to be preached at!"

The colossus slowly poured a glass of ice-water.

"Sir, you must understand—if you possess sufficient intelligence—that I can do nothing for you without your help." The bulbous lips writhed in a half-smile. "You have been rude, my friend—should I decide to treat your carcinoma I will leave you the poorer man by half your fortune before you are cured. That prospect, at least, you can understand."

Mortimer Dunlop, his seamed face livid with rage, got hastily to his feet and strode to the center door. He jerked the door open, slammed it behind him as he stormed from the room.

Unperturbed, Dmitri continued, "Mind came before matter; mind is the great motivator. Mind can conceive matter; matter cannot conceive anything, even itself.

"It is evident to any person who carefully considers these conclusions that in each one of us exists a spark, part and parcel of that great intangible Will which created all things. But this reasoning invariably leads to a conclusion so tremen-

WEIRD TALES

dous that the human consciousness, except in tare instances, rejects it.

"The conclusion is plain. The unfettered Will, by and of itself, can work miracles, move mountains, create and destroy!

"Listen carefully, for Coue and Pavlov and your own J. B. Watson were closer to the truth than they knew. . . .

"I pick up this coin, and I place it upon my wrist, so. Now I suggest to myself that it is very hot. But my conscious knows that it is not hot, and so I merely appear, to myself and to you all, a trifle foolish.

"Nevertheless, any hypnotist can suggest to a pre-hypnotized subject that the coin is indeed hot, and the subject's flesh will blister if touched with this same cold coin! . . .

"Now I will call my servant "

Placing his two enormous, shapeless hands on the table, Dmitri heaved himself to his feet, and a tremendous bellow issued from his barrel-like chest. That summons, though the words were Jost in a gulf of sound, was unmistakable, and presently the door opened and the little man, prim and neat and wholly a colorless personality, entered.

"Yes, Master."

Dmitri stood beside the table, his right hand resting heavily on the polished oak.

"Sit down, little Stepan."

The small man, the ghost of a pleased smile on his peasant face, sat down primly in the oaken chair and looked about the room with child-like pleasure. Obviously he was enjoying to the uttermost his small moment.

"You would prefer the sleep, little one? It is not necessary; we have been through this experiment many times together, you and I."

"I would prefer the sleep, Master," the little man said, with a slight shudder.

"Despite myself, my eyes flinch from the flame "

"Very well." Dmitri's voice was casual and low. "Relax, little one, and sleep. Sleep soundly "

He turned from his servant and picked up the fifty-cent piece. Turning it over and over in the fingers of his left hand he began to speak, slowly.

"I have told this subject's subconscious that its body is invulnerable to physical injury. Watch!"

The little man was sitting erect in the massive chair. His eyes were closed, his face immobile. Dmitri stooped, lifted an arm, let it fall.

"You are not yet sleeping soundly, Stepan. Relax and sleep—sleep "

Slowly the muscles in the little man's face loosened, slowly his mouth drooped, half open. Small bubbles of mucus appeared at the corners of his lips.

Dmitri seemed satisfied. Quietly, soothingly, he spoke.-

"Can you hear me?"

The man's lips moved. "I can hear you."

"Who am I?"

The answer came slowly, without inflection. "You are the Voice that Speaks from Beyond the Darkness."

Dmitri loomed above the chair. "You remember the truths that I have taught you?"

"Master, I remember."

"You believe?"

"Master, I believe. You have told me that you are infallible."

Dmitri straightened triumphantly and surveyed his silent audience. Suddenly, then, a roaring streamer of bluish flame lanced across the room. Dmitri had set the gasoline torch alight.

A woman was babbling hysterically. But above the steady moan of the flame Dmitri said loudly, "There is no cause for alarm. Now, observe closely. I am

THE THING ON THE FLOOR

285

going to go far beyond the ordinary hypnotist's procedure "

He carefully picked up, with the pliers, the fifty-cent piece. For a long moment he let the moaning flame play on the coin, until both coin and pher-tips glowed angrily.

Calmly, without warning, he dropped the burning coin on his servant's naked wrist!

A woman screamed. But, then, gasps of relief eddied from the tense audience. For, although the glowing whiteness of the coin had scarcely begun to fade into cherry-red, the man Stepan had shown no sign that he felt pain! There was no stench of burning flesh in the room. Even the fine hairs on the back of the servant's wrist, hairs that touched and curled delicately above the burning coin, showed not the slightest sign of singeing!

Dmitri's face was an obese smirk.

"In order that you may be convinced that this is neither illusion nor trickery," he grunted, "watch!" Carefully he tapped the coin with the pliers, knocking it from the man's wrist to the floor.

Around the coin's glowing rim smoke began to rise. ...

Still smirking, Dmitri poured a half-glass of ice-water on the red-hot coin, and the water hissed and fumed as it struck the incandescent metal. There was a little puff of thick smoke from the burning wood, and now the coin was cold —cold and black and seared.

No scar marked the servant's white wrist!

Dmitri rubbed his great; shapeless hands together. And, shuddering, Mary Roberts watched him, for she knew instinctively that this was, indeed, no trickery. . . .

Abruptly Dmitri lifted the roaring torch, thrust its fierce blast full in his

servant's face, held it there for a moment that seemed an eternity. Then he turned a valve, and the hot flame died.

Though the man Stepan* s face was streaked with carbon soot, the flesh was smooth and unharmed as though the blue flame had never been!

Dmitri looked at his guests, and chuckled!

"One more test," he boomed, tKen,, "and we will turn to more pleasant things. Believe me when I tell you that these horrors are necessary if you would have faith in me." He picked up the small automatic pistol. "Will someone examine this weapon, assure you all that it is fully-loaded ?"

No one offered to touch the gun. Dmitri shrugged. "Do not doubt me; the weapon is loaded, and with lethal ammunition." He wheeled, and for an instant the gun hammered rapidly, and on the breast of his servant's shirt, over the heart, there appeared suddenly a little cluster of black-edged holes, beneath which the white flesh gleamed unmarked. . . .