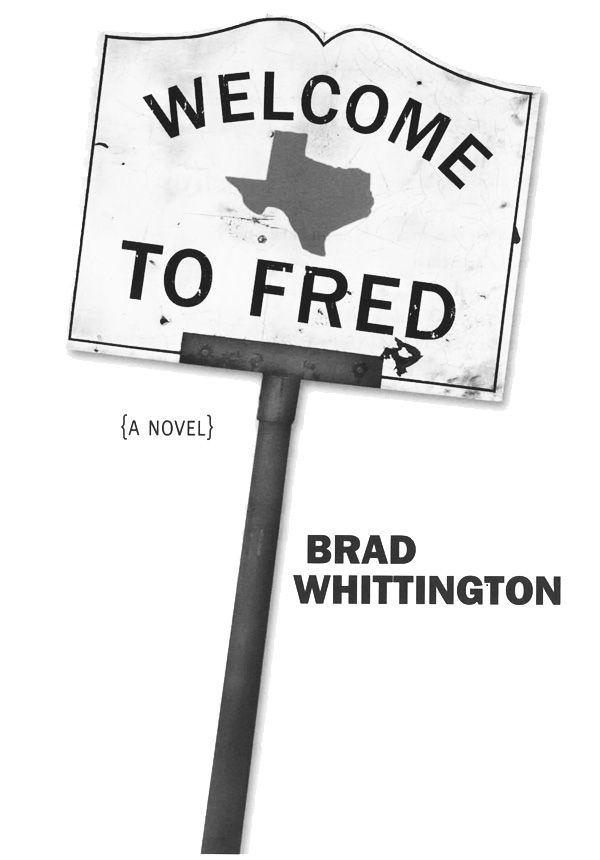

Welcome to Fred (The Fred Books)

Read Welcome to Fred (The Fred Books) Online

Authors: Brad Whittington

Table of Contents

Also by Brad Whittington

Buy a signed copy of the Fred books at SignedByTheAuthor.com:

“Whittington spins an enjoyable, literary story and is definitely a novelist to watch.”

— P

UBLISHERS

W

EEKLY

—

“I gobbled up the book in a couple of enjoyable evenings.”

— W

ANDA

A

DAMS

—

Honolulu Advertiser

“Brad Whittington is an artist with the pen.”

— E

THAN

C. M

C

D

ONALD

—

“Every once in awhile, you start reading a book and you start to smile. The images on the page begin to unfold, and you realize that this writer has, in some unaccountable and miraculous way, lived in your skin. Reading Brad Whittington’s prose was like that for me. By the time I’d finished the first couple of paragraphs, it was as if I’d found an old friend I never knew I had. Do yourself a favor: read

Welcome to Fred

.”

— T

HOM

L

EMMONS

—

author of

Jabez: A Novel

and the

Daughters of Faith Series

“I know a good, insightful coming-of-age story when I read one.

Welcome to Fred

is a joy. There are lessons to be learned here, but they’re all couched in Brad’s winsome prose so they don’t hurt. I commend this to you. This is good stuff. And I’m not just saying that because he’s from Fred.”

“Brad Whittington is a funny guy. And I know from funny. Everything he writes about Fred, Texas, is true. And I know from Fred because I once lived in Woodville, only twenty miles away as the crow flies through the Big Thicket of East Texas. According to some people, not far enough away from Fred.”

— R

OBERT

D

ARDEN

—

Assistant Professor of English, Baylor University; Senior Editor,

The Door

Magazine; Author of

Corporate Giants: Personal Stories of Faith and Finance

and more than twenty-five other books

“What do you get when you cross Dave Barry and Garrison Keillor? Two very irritated men. Besides that, you also get a great talent like Brad Whittington. Brad can take the awkward moments of growing up and turn them into something really ridiculous. But don’t take my word for it—visit Fred yourself.”

— R

OBIN

H

ARDY

—

author of the

Strieker Saga

, the

Sammy Series

, and the

Annals of Lystra

“It is always a joy to find a new writer that knows what he is doing.

Welcome to Fred

presents us with just such an author. Written with gravity and levity, this coming of age novel is a delight to read. As a young city boy is transported to very rural Texas, he must discover who he is. The process is both thoughtful and hilarious. I look for more good things from this author.”

— R

ICK

L

EWIS

—

Logos Bookstore, Dallas

“Brad Whittington is a welcome new voice in the world of fiction and faith. His fresh story of a young pastor’s son’s coming of age, filled with nostalgia and interesting characters, will make you smile.”

— C

INDY

C

ROSBY

—

author of

By Willoway Brook

© 2003 by Brad Whittington

All rights reserved

Kindle Edition 2011 Wunderfool Press

produced by

ePubEdition.com

978-1-937274-00-9

Quote, partial lyrics of “Child of the Wind,” written by Bruce Cockburn, © 1991 Golden Mountain Music Corp., used by permission

Unless otherwise stated all Scripture citation is from the RSV, Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyrighted 1946, 1952, © 1971, 1973.

For Robin Hardy,

who deserves most of the blame for the fact you are holding this book in your hand right now.

| | Little round planet In a big universe Sometimes it looks blessed Sometimes it looks cursed Depends on what you look at obviously But even more it depends on the way that you see | |

| | -- Bruce Cockburn, “Child of the Wind” |

CHAPTER ONE

I found it in the back of a drawer in his rolltop desk. Not that I was looking for it. I was just cleaning out the desk. I didn’t mind. In fact, I preferred it to cleaning out the closets, which Hannah was doing, or cataloging the furniture, the job Heidi had chosen.

It was a small, black, cardboard ring binder with a white label. The printing on the label was definitely Dad’s—a small and precise lettering from a hand that seemed to be more comfortable with cuneiform than the English alphabet. It read: “The Matthew Cloud Lexicon of Practical Usage.”

Intrigued, I flipped through it. There were tabbed dividers for each letter of the alphabet. Each page appeared to have a single entry consisting of a word and a definition. I flipped back to the beginning. The first entry was:

Adolescence:

Insanity; a (hopefully) temporary period of emotional and mental imbalance.

Symptoms:

mood swings, melancholia, rampant idealism, insolvency. Subject takes everything too seriously, especially himself.

Causes:

parents, raging hormones.

Known cures:

longevity, homicide.

Antidotes:

levity, Valium.

That prompted a chuckle. I had no doubt this entry had been written while Jimmy Carter grinned from the Oval Office. I sat back in the swivel chair for a welcome bit of reflection, which was to be expected, seeing as how we were settling Dad’s estate. Nostalgia traps were likely to be rampant in closets and drawers all over the house.

I suppose adolescence is somewhat like insanity. In both cases isolation is sometimes seen as a method for limiting the damage. I suspected that in 1968, when I turned twelve, my parents must have sensed the initial stages of the dreaded malady. I could think of no other reason why they would have moved from metropolitan America to Fred, Texas.

I know you’re dying to ask, so I might as well tell you right up front. Fred is located in East Texas, between Spurger and Caney Head. It looks different now, but back then it spanned nine-tenths of a mile between city limit signs and included six buildings of note: a general store, an elementary school, a Baptist church, a hamburger joint, a service station, and a post office. The nearest movie theater was sixteen miles south, in Silsbee. The nearest mall appeared in the early 1970s, forty miles south in Beaumont.

In many ways Fred was idyllic. There was nothing but pine woods and dirt roads to be explored, creeks to be splashed through and swam in, and fresh air to suck into your lungs in an eternal draught. Since I was only twelve and had not yet succumbed to the symptoms of adolescence, I loved it. By the time I hit sixteen, however, Fred’s greatest assets had become, for me, its greatest liabilities. There was nothing but pine woods, dirt roads, and creeks.

Still, as a twelve-year-old, I reveled in the unruly semiwildness of the Big Thicket. I delved pine thickets, ferreting out hidden sanctuaries in oil-company tracts, miles from any road. The lust for adventure shared by all young boys provided me with traveling companions.

Swaying one hundred feet in the air at the top of a pine and surveying a green ocean, we were Columbus, devoutly seeking land after months at sea. Cresting the top of a limestone outcrop and finding a bottomless pool in an abandoned quarry, we were Balboa gazing in wonder upon the Pacific. Picking our way through a stagnant bayou, balanced precariously on moss-covered logs and leaping from one knot of ground to another, we were Francis Marion —the Swamp Fox— cleverly eluding the British once again. Following the meandering trail of a dried creek bed, we were Powell winding through the Grand Canyon.

But even in the passion of exploration, caught in the frantic surmise that we were probably the first humans to have ever seen a particular secluded hideout (deduced from the absence of beer cans or other trash), I felt the subtle walls as real as stone between me and my companions.

For example, the names Balboa, Francis Marion, and Powell meant nothing to them. (Of course they knew of Columbus. After all, he had a day named after him to guarantee his immortality.) One of my failings—academic success—didn’t endear me to my peers.

Language was yet another plank in the scaffold of my isolation. My parents had taken great pains to weed ungrammatical habits out of their children, with mixed success. In my speech such phrases as “I done did,” “I seen him,” or “I ain’t” were conspicuous by their absence. I discovered that Fredonians didn’t trust anyone who talked differently.

But those differences paled against the Great Divider. We had moved to Fred because my father was the new pastor of the Baptist church. I was a preacher’s kid (or PK, as we say in the business). Nothing is guaranteed to bring a spicy conversation or a racy joke to a dead halt like the arrival of the preacher’s kid. I became as accustomed to seeing conversation die when I approached as a skunk expects the crowd to part when it walks through.

Nonetheless, I tolerated those inconveniences in my preadolescent state, glorying in the remote wilderness like a hermit. It was only when hormonal changes initiated the symptoms of the malady of adolescence that I began to languish rather than glory in my isolation from modern culture. The crude tree house that had served variously as fort, ship, headquarters, prison, hideout, and throne now did duty as a sanctuary of solitude to which I retreated to puzzle out Fred’s provincial culture and my place in it.

Many teenage boys would have loved such an environment; indeed, most native Fredonian teens thrived in it. With graceless effort they shot deer, snagged perch, played football, and rattled in pickups down dirt roads. George Jones and Tammy Wynette oozed from their pores like sweat. Under black felt Stetsons they sported haircuts as flat as an aircraft carrier. Pointed boots with taps announced their coming as they approached, and leather belts with names stamped on the back proclaimed their identity as they departed. They dipped snuff, spitting streams like some ambulatory species of archerfish. Their legs fit around a horse as naturally as a catcher’s fist nestles in his mitt. They split logs and infinitives, chopped wood and prepositional phrases, dangled fish bait and participles—all with equal skill.

However, in the throes of the teenage condition, I gradually grew dissatisfied with this remote Eden. Although native Texans, our family had spent four years in Ohio. (Since Yankeeland is technically in the same country, no visa or inoculations are required to move there. However, as far as Texans are concerned, Yankeeland is a foreign country and travelers should update their cultural resistance immunization before spending any significant time there.) Nothing can stop the onslaught of adolescence, but perhaps my parents had hoped that my first eight years in Fort Worth were sufficient to inoculate me against Northern influences. Unknown to them, however, I contracted the germs of a companion disease during my four years of Yankee exile.

In the North, I watched in fascination as hippies and “flower power” bloomed around me. Although too young to participate, I was mesmerized by Peter Max, paisley, and psychedelic posters. Still, I arrived in Fred seemingly intact. But as the symptoms of adolescence surfaced, they triggered the dormant 1960s-counterculture virus, which in turn sprouted in that unlikely Texas garden.

Fred was no place for a would-be flower child seeking sympathetic flora. The British Invasion of the seventeenth century took more than one hundred years to reach East Texas. As I surveyed Fred, I suspected it would take the second British Invasion—the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin—at least that long to reach me.

My distinguishing features, combined with my growing detachment, separated me from the culture short of complete social isolation. Consequently, I remained on the outside looking in, spending most of my teenage years observing rather than participating.

But I guess I should start at the beginning.