Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College (22 page)

Read Welcome to Your Child's Brain: How the Mind Grows From Conception to College Online

Authors: Sandra Aamodt,Sam Wang

Tags: #Pediatrics, #Science, #Medical, #General, #Child Development, #Family & Relationships

The ability to regulate your own behavior is important not only for academic achievement but also for interpersonal success. Children who are skilled at behavioral self-control show less anger, fear, and discomfort and higher empathy than their peers of the same age. Other people rate these children as more socially competent and more popular, even years later, probably because they are good at regulating their own emotions and taking the emotions of others into account.

Some amount of brain maturation is a necessary first step in the development of self-control. Around ten months, in the earliest sign of this capacity, babies are able to choose which aspects of the environment to select for attention (as opposed to paying involuntary attention to whatever suggests itself; see

chapters 10

and

28

). Once this occurs, they can comfort or distract themselves and sometimes change their behavior instead of persisting on a course of action that’s not effective, as younger infants do. The more complex ability to deliberately inhibit behavior, control impulses, and plan actions, called

effortful control

, is first seen around twenty-seven to thirty months of age. It allows children to do things like remember to use their inside voice when they are excited or keep their hands out of the cookie jar (at least some of the time). Toddlers develop the ability to inhibit behavior on command between their second and third birthdays. Effortful control then improves rapidly until the fourth birthday and more slowly through age seven. Resistance to distraction continues to get better throughout childhood, reaching adult values in the middle to late teens.

Two related skill sets depend on similar brain regions and thus tend to develop in parallel with effortful control. One is

cognitive flexibility

, the ability to find alternative ways to achieve a goal if the first attempt does not succeed, and to adjust behavior to fit the situation, like not running near the pool. The other is

working memory

, the ability to remember task-relevant information for a short period of time, such as recalling which solutions to a puzzle you already tried. Together, these three abilities are collectively called

executive function

.

As these abilities grow with age, children become progressively better at sequencing behavior appropriately, keeping track of multistep tasks, and resisting or recovering from distractions. Executive function, which provides the core ingredients for self-control in adulthood, depends on the

prefrontal cortex

and the anterior cingulate cortex. The prefrontal cortex shapes behavior in pursuit of

goals by activating or inhibiting other brain regions. The anterior cingulate is activated by tasks that require cognitive control, particularly monitoring and detecting errors in performance and deciding among conflicting cues. Another part of the anterior cingulate is connected with the orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala and is involved in regulating emotions.

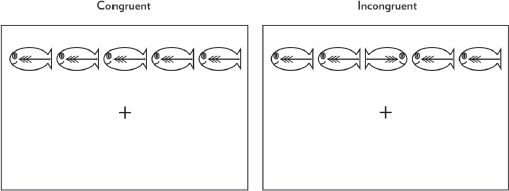

One measure of a child’s growing executive function is the strength of his cognitive control. This ability is typically measured by the

conflict cue task

, in which children are asked to rapidly detect the appearance of a target. This task is easier (and so performance is faster) if the child knows in advance where the target will appear. In a simple version of the task (see figure below), the target is preceded by one of two cues, a row of five fish that all face toward the target’s future location (

congruent condition

), or another row with the center fish facing the target location and the other four fish facing the wrong way (

incongruent condition

). Response times are slower, for children and adults, when faced with incongruent conditions, because the brain must inhibit the automatic tendency to follow the majority of cues and instead concentrate on the center fish alone. Performance on this test correlates with parents’ evaluations of their children’s self-control ability.

Stable individual differences in these measures become evident during early childhood. The ability to self-regulate is moderately heritable; some evidence suggests that this has to do with the genes that regulate the neurotransmitters dopamine and

serotonin

. But children’s experiences also have an important effect on their self-control in studies that take genetic influences into account.

Four-year-olds who do well on the marshmallow task typically distract themselves from thinking about the tempting object during the delay period. They cover their eyes, turn their backs on the marshmallow, or try to think about something else. One of the tricky aspects of self-control is that it has a certain circular quality: it takes discipline to learn discipline. Children who can focus on a task without giving in to distractions are also going to be better at improving this ability through practice. The key is for parents and teachers to provide scaffolding to support the learning process until the child’s self-control is strong enough to stand on its own (see

chapter 29

). This process is easier, especially in young children, if a child finds the task rewarding. So keep an eye out for age-appropriate, multistep projects, like making art or building something, that your child enjoys.

PRACTICAL TIP: IMAGINARY FRIENDS, REAL SKILLS

An average four-year-old child who is asked to stand still for as long as possible can manage it for slightly less than one minute. If he’s asked to pretend he is a guard outside a castle, though, he can hold his pose four times that long. The reason is simple: pretending is fun, which means it’s easy to get children to participate enthusiastically. Children can choose games that reflect their own interests, so they can supply their own motivation for achievement, which teaches self-control—an ability that is more useful in adulthood than modifying your behavior to please others. Most important, imaginative play has rules that children take seriously. To play school, you have to act like a teacher or a student, and inhibit your impulses to act like a fighter pilot or a baby. Following these rules provides children with some of their earliest experiences with controlling their behavior to achieve a desired goal.

An innovative preschool program called Tools of the Mind has achieved remarkable success using the power of play to teach disadvantaged children how to control their impulses and organize their behavior in pursuit of goals. Children are asked to plan how they want to spend their play time (“I am going to take the baby to the doctor”) and then to stick to that plan. Teachers use physical reminders to help children regulate turn-taking, such as having one child hold a cardboard ear and another child a mouth to remind them who is supposed to be listening and who is supposed to be talking right now. The goal is to help children develop the ability to control their own behavior, rather than simply following rules to gain gold stars or avoid time-outs.

The program is only a few years old, but the early data are exciting. In one study, done in a low-income neighborhood, more than twice as many Tools of the Mind students could successfully perform a difficult attention-demanding task, in comparison to those who were in another preschool program. We look forward to future research aimed at finding out how long these self-control gains last, whether they improve later academic performance, and which of the techniques used in the program are most effective. In the meantime, we encourage parents to adopt some of these techniques to help their three- and four-year-olds learn to regulate their own behavior through imaginative play.

PRACTICAL TIP: LEARNING TWO LANGUAGES IMPROVES COGNITIVE CONTROL

Becoming bilingual gives children cognitive advantages beyond the realm of speech. Learning multiple languages is challenging in part because the person must direct attention to one language while suppressing interference from the other.

This interference causes bilingual people to be slower at retrieving words and have more “tip-of-the-tongue” experiences than monolingual people.

There are benefits to meeting these challenges. Bilingual children outperform monolingual children on tests of executive function. Before their first birthday, bilingual children learn abstract rules and reverse previously learned rules more easily. They are less likely to be fooled by conflicting cues, such as a color word like

red

written in green ink, which psychologists call the Stroop task. This pattern continues into adulthood and even shows up in nonverbal tasks. Selecting appropriate behavior in two different languages seems to strengthen bilingual children’s ability to show cognitive flexibility according to context—an aspect of self-control.

Bilingual children also outperform monolingual children on tests that measure the ability to understand what other people are thinking (see

chapter 19

). This advantage may develop because bilinguals get more practice at taking the perspective of other people, since they need to choose the appropriate language for the person they’re talking to.

Bilingual people may exert cognitive control not only better, but by using different brain areas. During a task that requires them to resolve differences between two conflicting sources of information, bilingual children’s brains show activation not just in the portion of the prefrontal cortex that everyone uses for conflict resolution, but also in Broca’s area, the speech region that processes grammatical rules.

Bilingualism may also protect the brain from cognitive decline in aging. People who have spoken two languages actively for their entire lives experience the onset of dementia four years later, on average, than their peers who spoke only one language.

That’s a lot of advantages—and we haven’t even mentioned the most important use of a second language, to communicate with people.

Succeeding at challenging self-control tasks builds more success, but repeated failure may instead teach the child that there’s no point in trying.

Here’s some even better news. Improvement of self-control is not limited to a sensitive period (see

chapter 5

). We all know that even in adults, the ability to control your own behavior is limited, but it can be increased by training. As the psychologist Roy Baumeister puts it, willpower is like a muscle: the more you use it, the better it works. His studies show that self-control can be improved by practicing any sort of self-control, from dieting to money management to brushing your teeth with your left hand, on a regular basis. College students who did these exercises for several weeks reported improvements in their ability to complete a variety of tasks requiring self-control, from going to the gym regularly to managing money to doing housework. Indeed, the legendary tough parenting style of many Asian parents appears to be directed specifically at instilling self-discipline, which could account for the high achievements of their children.