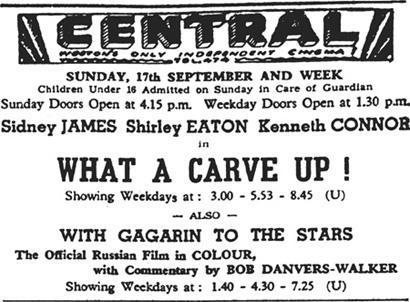

What a Carve Up! (6 page)

Authors: Jonathan Coe

Six years later, Yuri would be dead, his MiG-15 diving inexplicably out of low cloud and crashing to the ground during an approach to landing. I was old enough by then to have imbibed some of the prevailing distrust of all things Russian, to take notice of the dark mutterings about the KGB and the displeasure my hero may have incurred in his own country for having so charmed the cheering Westerners. Perhaps Yuri really had condemned himself the day he shook hands with all those children at Earl’s Court; and yet it had been them that I wished dead at the time. Whatever the explanation, I can no longer recapture or even imagine the state of innocence in which I must have sat through that afternoon’s artless, stentorian celebration of his achievement. I wish that I could. I wish that he had remained an object of unthinking adoration, instead of becoming another of adulthood’s ubiquitous, insoluble mysteries: a story without a proper ending. I was soon to find out about those.

∗

Just as the lights were going down for the second time, and the censor’s certificate appeared on the screen to announce the beginning of the main feature, my mother leaned over and started whispering across the top of my head.

‘Ted, it’s nearly six o’clock.’

‘What about it?’

‘Well, how long’s this film going to go on?’

‘I don’t know. About ninety minutes, I suppose.’

‘Well then we’ve got to drive all the way back. It’ll be hours past his bedtime.’

‘It won’t matter just this once. It is his birthday, after all.’

The credits had started and my eyes were fixed on the screen. The film was in black and white and the music, although it was not without a certain jokiness, somehow filled me with foreboding.

‘And then there’s dinner,’ my mother whispered. ‘What are we going to do about dinner?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Stop somewhere on the way back.’

‘But then we’ll be even later.’

‘Just sit back and enjoy it, can’t you?’

But I noticed that for the next few minutes, my mother kept leaning towards the light in order to sneak regular glances at her watch. After that I don’t know what she was doing, because I was too busy concentrating on the film.

It told the story of a nervous, mild-mannered man (played by Kenneth Connor) who was startled in his flat late one night by the arrival of a sinister solicitor. The solicitor had come to tell him that his rich uncle had recently died, and that he was required to travel immediately up to Yorkshire, where the reading of the will was to take place at the family home, Blackshaw Towers. Kenneth went up to Yorkshire by train in the company of his friend, a worldly bookmaker (played by Sidney James), and found that Blackshaw Towers was situated on a remote edge of the moors far from the nearest village. Failing to find a taxi, they accepted a lift in a hearse, which left them stranded on the moors in the middle of a dense fog.

When they finally arrived at the house, they could hear the distant howling of dogs.

Sidney said: ‘Not exactly a holiday camp, is it?’

Kenneth said: ‘There’s something creepy about this place.’

The rest of the audience seemed to be finding it funny, but by now I was thoroughly scared. I had never been taken to see anything like this before: although it wasn’t strictly a horror film, the detail was very convincing, and the gloomy atmosphere, dramatic music and perpetual sense that something terrible was about to happen all combined to torment me with a strange mixture of fear and exhilaration. Part of me wanted nothing more than to run out of the cinema into what was left of the daylight; but another part of me was determined to stay until I found out where it was all leading.

Kenneth and Sidney crept into the hallway of Blackshaw Towers, and found that the house was just as eerie as it had looked from the outside. They were met by a gaunt and forbidding butler called Fisk, who led them upstairs and showed them to their rooms. Much to his dismay, Kenneth found himself not only being taken to the East Wing, far away from his friend, but being required to sleep in the very room where his late uncle had died. Soft, unsettling organ music could be heard in the corridor. They went downstairs again and were introduced to the other members of Kenneth’s family: his cousins Guy, Janet and Malcolm, his Uncle Edward, and his mad Aunt Emily, for whom time seemed to have stood still ever since the First World War. Just before the solicitor began reading the will, another woman appeared: a young, blonde and beautiful woman played by the actress Shirley Eaton. She was there because she had nursed Kenneth’s uncle during his final illness. There weren’t enough chairs for everybody to sit around the table, so Kenneth had to balance on Shirley’s knee. He seemed quite pleased about this.

The will was read and it transpired that none of the relatives had been left anything at all: they had been made the victims of a practical joke. They argued with each other bitterly as they began getting ready for bed. Then, suddenly, all the lights in the house went off. By now there was a terrible storm raging outside and Fisk suggested that the generator must have broken down. Kenneth and Sidney volunteered to go with him and investigate. When they reached the shed which housed the generator they found that the machinery had been smashed to pieces. They started going back towards the house, but were amazed to find Uncle Edward sitting on a deck-chair in the middle of the lawn, drenched by the pouring rain.

Sidney said: ‘What’s he sitting out there for?’

Kenneth laughed and said: ‘It’s unbelievable. He’ll catch his death of – death of–’

He gave a violent sneeze, and Uncle Edward fell stiffly off the deck-chair. He was dead.

Kenneth said: ‘Sid … is he?’

Sidney said: ‘Well if he ain’t, he’s a very heavy sleeper.’

There was a terrific thunderclap, and my mother leaned across to my father. She whispered: ‘Ted, come on, let’s go.’

My father was laughing. He said: ‘What for?’

My mother said: ‘It’s not suitable.’

Kenneth said: ‘Well I mean, we can’t leave him round here, can we? Look, let’s put him in the potting shed – it’s over there somewhere.’

There was more audience laughter as Kenneth, Sid and the butler attempted to pick up Uncle Edward’s corpulent body.

Sidney said: ‘Look, it’d be easier to bring the potting shed over to him.’

Even Grandma laughed at that. But my mother just looked at her watch again and my father, perhaps imagining that I might be frightened, ruffled my hair and laid his arm close by, so that I could take hold of it and lean against him.

Kenneth and Sid went back inside and told the rest of the family that Uncle Edward had been killed. Sid tried to telephone the police, only to discover that the line had been cut off. Kenneth said that he was going home, but the solicitor pointed out that the moors were impassable in this weather, and that if he were to leave now, he would be the first to come under suspicion for Edward’s murder. He recommended that everyone should go to bed at once and lock their doors.

Fisk said: ‘It’s only the start of it. There’ll be another one yet, mark my words.’

Sidney said: ‘Good-night, laughing boy.’

Kenneth and Sidney went back upstairs, but then, left to his own devices, Kenneth found it easy to get lost in the rambling old house. He opened the door to what he thought was his bedroom and discovered that it was already occupied by Shirley, wearing only her slip and about to put on a nightgown.

Kenneth said: ‘I say, what are you doing in my room?’

Shirley said: ‘This isn’t your room. I mean, that isn’t your luggage, is it?’

She clutched the nightgown modestly to her bosom.

Kenneth said: ‘Oh, blimey. No. Wait a minute, that’s not my bed, either. I must have got lost. I’m sorry. I’ll – I’ll push off.’

He started to leave, but paused after only a few steps. He turned and saw that Shirley was still holding on to her nightgown, unsure of his intentions.

My mother stirred uneasily in her chair.

Kenneth said: ‘Miss, you don’t happen to know where my bedroom is, do you?’

Shirley shook her head sadly and said: ‘No, I’m afraid I don’t.’

Kenneth said: ‘Oh,’ and paused. ‘I’m sorry. I’ll go now.’

Shirley hesitated, a resolve forming within her: ‘No. Hang on.’ She gestured with her hand, urgently. ‘Turn your back a minute.’

Kenneth turned, and found himself staring into a mirror in which he could see his own reflection, and beyond that, Shirley’s. Her back was to him, and she was wriggling out of her slip, pulling it over her head.

He said: ‘J— just a minute, miss.’

My mother tried to get my father’s attention.

Kenneth hastily lowered the mirror, which was on a hinge.

Shirley turned to him and said: ‘You’re sweet.’ She finished pulling her slip over her head, and started to unfasten her bra.

My mother said: ‘Come on. We’re going. It’s far too late already.’

But Grandpa and my father were both staring goggle-eyed at the screen as the beautiful Shirley Eaton took her bra off with her back to the camera, while Kenneth heroically tried to stop himself from peeping into the mirror which would have yielded a precious glimpse of her body. I was staring at her too, I suppose, and thinking that I had never seen anyone so lovely, and from that moment it was no longer Kenneth she spoke to but me, my own nine-year-old self, because I was now the person who had lost his way in the corridor, and, yes, it was me that I saw on the screen, sharing a room with the most beautiful woman in the world, trapped in that old dark house in that terrible storm in that shabby little cinema in my bedroom that night and in my dreams forever afterwards. It was me.

Shirley emerged from behind my head, her body swathed in the knee-length gown, and said: ‘You can turn round now.’

My mother stood up, and the woman behind her said: ‘For Heaven’s sake sit down, can’t you.’

On the screen, I turned and looked at her. I said: ‘Cor. Very provoking.’

Shirley brushed back her hair, embarrassed.

My mother grabbed my hand and pulled me out of my seat. I let out a little howl of protest.

The woman behind us said: ‘Sssh!’

Grandpa said: ‘What are you doing?’

My mother said: ‘We’re leaving is what we’re doing. And you’re coming too, unless you want to walk all the way back to Birmingham.’

‘But the film hasn’t finished yet.’

Shirley and I were sitting on the double bed together. She said: ‘I’ve a proposal to make.’

Grandma said: ‘Come on then, if we’re going. We’ve got to stop somewhere for dinner, I suppose.’

On the screen, I said: ‘Oh?’

Off the screen, I said: ‘Mum, I want to stay and see the end.’

‘Well you can’t.’

My father said: ‘Oh well. Looks like we’ve been given our marching orders.’

Grandpa said: ‘I’m staying put. I’m enjoying this.’

The woman behind us said: ‘Look, I’m going to call the management in a minute.’

Shirley moved closer towards me. She said: ‘Why don’t you stay here tonight? I don’t fancy spending the night alone, and we’d be company for each other.’

My mother grabbed me underneath the armpits and lifted me out of my seat, and for the second time that day I burst into tears: partly out of real distress and partly, no doubt, because of the sheer indignity of it. I hadn’t been picked up like that since I was tiny. She pushed past the other people in the row and started carrying me down the steps towards the exit.

On the screen I seemed to be uncertain how to respond to Shirley’s offer. I mumbled something but in the confusion I couldn’t hear what it was. I could see Grandma and my father following us into the aisle and Grandpa rising reluctantly from his seat. As my mother pushed open the door which led to the chill concrete stairs and the salty air, I turned and caught a last glimpse of the screen. I was leaving the room but Shirley didn’t know this because she had her back to me and was fiddling with the bed.

Shirley said: ‘I’ll be quite all right on the –’ She turned, and stopped. She saw that I had gone.

‘– chair.’

The door closed and my family were clattering down the stairway. I shouted, ‘Let me down. Let me

down

!’, and when my mother put me down I immediately tried to run back up the stairs into the cinema, but my father caught me and said, ‘Where do you think you’re going?’, and then I knew that it was all over. I pummelled him with my fists and even tried to scratch his cheek with my fingernails. For the first and only time in his life my father swore and smacked me, hard, across the face. After that, we were all very quiet.

∗

In the car going home, I pretend to be asleep, but in reality my eyelids are not properly closed and I can see the light from the amber roadlamps flashing across my mother’s face. Light, shadow. Light, shadow.

Grandpa says, ‘Now we’ll never know what happened,’ and from the back of the car Grandma says, ‘Oh do shut up,’ and she pokes him in the shoulder.

I am no longer crying, no longer even sulking. As for Yuri, he has been quite forgotten and I can barely even call to mind the film which so excited me a couple of hours ago. All I can think of is the fearsome atmosphere of Blackshaw Towers, and the inexplicable scene in the bedroom where this beautiful, beautiful woman asks Kenneth to spend the night with her, and he runs away when she isn’t looking.