What Stays in Vegas (24 page)

Read What Stays in Vegas Online

Authors: Adam Tanner

Over time, Prall expanded his reach to other high schools and even Illinois State University. A good friend helped out and encouraged him to present a tougher façade. When classmates' parents went out of town, Prall and his fellow dealers offered to sponsor parties at their homes. They would foot the bill for kegs and then take up residence in a corner, taking in hundreds or even thousands of dollars in a night in entrance fees. By promising to make the host kid popular overnight, they uncovered a steady stream of houses for their events.

The fact that Prall was up to something did not escape his parents' notice. His mother occasionally found large wads of cash in his room. She and Prall's father suspected he was running with a dubious crowd. At one point his father, who in his courtroom had seen what happened to kids who ran afoul of the law, confronted Prall. “I think you're up to something,” the elder Prall told his son. “If you keep it up, you're going to get in trouble.”

Prall ignored the warnings. He kept dealing all through high school, raking in tens of thousands of dollars. Still, when his friend branched out into cocaine, Prall stuck to weed. He feared trouble from the kind of people who bought cocaine. Good grades and a solid middle-class background helped keep Prall below the radar. Even with all the extracurricular dealing, Prall graduated in the top 10 percent of his class. The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign accepted him, and he planned to matriculate in the fall and major in finance.

That summer, Prall moved out of his parents' house and into a cheap summer sublet he shared with some high school friends. It was a rite of passage for newly minted high school graduates in Bloomington,

who got their first taste of living on their own by taking up residence in houses vacated by the city's college kids. One July day he was relaxing with a friend on the porch when plainclothes detectives arrived: “We're looking for Kyle Prall.”

The cops told Prall they had to take him downtown because he had an outstanding traffic ticket. It wasn't the first time Prall had been hauled to the station. The previous arrests had all been for relatively minor violations too, like underage drinking. He always seemed to have a beer in his hand when police raided parties. But this time it was different.

He knew things were bad when officers took him through the back door. They took his mug shot and led him down a long hallway lined by holding cells. Prall recognized many of the shoes lined up outside the cell doors. The authorities had nabbed almost all his drug-dealing friends. But as Prall looked around the room, he noticed that one pair of shoes was missing. His good friend who had helped show him the ropes in the business had escaped arrest.

As he sat in his jail cell, Prall thought back to an episode that he now realized had led to his downfall. One cold winter day the previous winter, his pal had telephoned and said he had run out of marijuana and had to buy in bulk. Prall headed to his house, albeit a bit grumpily, as wholesale distribution meant far less profit than dealing to individual customers. A few blocks from the house, Prall noticed a Ford Crown Victoria parked on the side of the road. A man was sitting inside, reading a newspaper. “There is no way that guy is just sitting in his car reading his newspaper,” Prall thought.

Prall called his friend and told him what he had seen. Perhaps he should not come over, he suggested. By that point in his dealing career, Prall had developed an instinct for signs of trouble. Yet he remained gullible enough to trust his savvy partner, who had already served time in juvenile detention. “It's okay, come on over,” the friend assured him.

When Prall arrived, he found his friend acting a bit stiffly. Something was not right about the way he was talking when Prall handed him the marijuana he wanted to buy. “It's a quarter-pound, right?” he asked a few times. Prall didn't know it, but that was the day the other

teen had become a police informant. That winter visit was one of four during which the friend gathered evidence against Prall using a wire taped to his chest.

The friend-turned-informant had grown up on the poorer side of town, and he had not received the same breaks in life. His father worked as a manual laborer, a world away from the courts of Prall's father. Prall knew his friend got along poorly with his father and stepmother, and he was always looking for a way to make a fast buck. At the Catholic school he attended, he stole lunch tickets and sold them to other kids for half price. He also pinched the answers to tests and made a tidy sum selling them. In fifth grade, his Catholic school kicked him out.

6

Most of the students avoided the kid. But there was something about him that appealed to Prall, who had an innate rebellious streak. As he hit puberty Prall chafed at the well-off middle-class life he had enjoyed. His new friend, on the other hand, seemed to be the ballsy, live-for-the-day kind of kid Prall wished he was. Additionally, he used his outside earnings to dress flashily, and that appealed to Prall.

The two started out in business together in the seventh grade, when both took on newspaper delivery routes. On busy days they would lend each other a hand. They also got together after school to get into mischief. The friend seemed to bring out Prall's wild side. The two would go out and steal other kids' candy on Halloween or shoot water balloons, vegetables, and other objects at people with a powerful long-distance slingshot.

The friend typically led the way. In the summer before high school he started dealing small amounts of marijuana, charging $5 a joint. Over time Prall grew curious, and late in his freshman year he started smoking weed. The amount his friend earned from dealing began to impress him. It looked like easy money. Hardened by a tougher upbringing, he schooled Prall in street savvy. Prall impressed his friend with how quickly he picked up the business. But the tougher kid couldn't figure out why someone with so much going for him would risk it all to sell dope.

“Your family's well-off,” he said to Prall one day. “You're guaranteed to go to college. You're smart as fuck. Why in the world do you want to sell drugs and hang out with these scumbags?”

Prall had a ready reply: “Because it's fucking boring, dude. It's fucking boring hanging out with fucking dorks.”

In December 1996, their son's senior year, the friend's father and stepmother discovered a stash of marijuana in their basement. It was the last straw after a series of troubling incidents. They had been trying to get him to shape up for years and worried about what would happen if he had to go to jail as an adult. They knew a detective and decided that their best hope was to try to work out some kind of a deal. Prall's friend was trapped. He had turned eighteen earlier that year. If he was arrested, there was no more juvenile hall. To avoid jail, he agreed to entrap other dealers by wearing a wire.

The friend-turned-informant recorded a series of conversations with Prall, and the evidence was irrefutable. Prall pleaded guilty to one felony count out of four original charges. The legal process dragged on for months, giving him enough time to finish his first term of freshman year at college before serving his time. That term Prall earned an A plus in a philosophy course on logic and reasoning.

7

In 1998, as his classmates headed off to their summer jobs, Prall turned himself in to the DeWitt County jail. After sixty days, he was set free. He also paid $1,550 in fines.

At the University of Illinois, Prall majored in finance and held part-time jobs delivering pizzas, working as a waiter, and helping at construction sites. Although he also got into several minor scrapes with the law, Prall graduated from college with an overall B-plus average. After studying with flash cards at the gym, in classes, and at coffee shops, he passed the Certified Public Accountant exam in 2002. With his criminal record, Prall did not find it easy to get hired, but a friend of his father's granted him an interview to work at his accounting firm. He started the job in the late summer after college, but quickly grew disillusioned with conventional work. “Absolutely hated it. It was mind-numbingly boring,” he says.

In the years that followed, Prall drifted through a series of jobs. He analyzed credit reports for a Chicago-area bank, moved to Cleveland

and then New York, where he landed a job at a small investment bank specializing in bankruptcy restructuring. He was earning $100,000 a year, enough to afford a fifth-floor walkup apartment on Manhattan's Upper East Side. He met many clients and began to think big. “You know what? I could do what these guys do. Why am I not sitting on that side of the table?” he wondered. He decided to call it quits and moved in with a friend in Austin, Texas, looking for new opportunities.

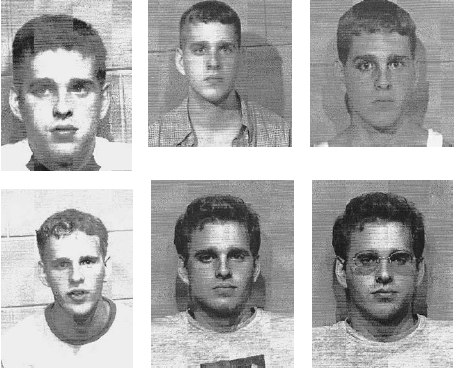

Kyle Prall's mug shots from his younger days. Source: McLean County Sheriffâs Office.

Mug Shot Empire

Prall's personal-data empire lies in an office park overlooking downtown Austin, the Texas capital. The company does not list its address on its website or in local directories, and workers treat their location

as a corporate secret. The sign on the door offers no indication of the company's business and could easily belong to a lawyer's or insurance office.

8

The desire for anonymity is explained by Ryan Russell, Prall's chief investor: “I'm tired of death threats. I've never dealt with something this controversial. I've never dealt with something that made me fear for my personal safety.”

Inside, the atmosphere differs little from that of a typical startup. Computer engineers tap away on their keyboards in a large open space ringed by sparsely decorated offices. By 2014

bustedmugshots.com

had gathered more than forty million arrest records. For most of the company's history it made money in part by charging people to pull their files from the service. That, understandably, outraged some of its targets, who think such a service is little more than an extortion racket.

Paola Roy and Janet LaBarba are just two of millions whose images appeared prominently in Internet searches thanks to Prall's company. Images posted by users on Facebook, Flickr, or other sites typically do not have the same sophisticated coding as Busted! uses, so they fall lower down in Internet searches.

Prall says he is performing a public service by publicizing the photos and helping those arrested on minor charges by allowing the removal of images. “We're not forcing you to pay for anything,” Prall says. “To me it's not a dagger in the heart. It's a public record: it belongs to the public.”

With twelve million to fourteen million arrests in the United States every year, most commonly for drugs, theft, and drunk driving, Prall has plenty of public records to chase, plenty of people to humiliate.

9

In total, the FBI maintains fingerprints and criminal histories on seventy-six million people.

10

Prall defends posting images of people like Roy, even for such trifling matters. “We do not feel it should be up to us to decide which cases are worthy of meeting a nebulous standard of âserving public good,' so we instead allow the citizens to make those kind of judgment calls themselves,” he says. “Unlike the traditional media that cherry-picks the cases they cover based on their marketability, we make as much information as possible without filtering or putting an editorial

spin on the incident. Of course, some cases will be more serious than others, but that is a very subjective standard that we do not feel is our place to define.”

Why do local agencies provide Busted! any mug shots at all? Government bodies have long distributed public records in an effort to provide openness about their activities. Each US state and court system maintains its own open records rules, but for many decades they have collected an increasing amount of personal documents and typically made them available to the public.

11

Before electronic records, obtaining a personal record or a mug shot required going down to a city office or courthouse to fetch the record manually, or making a request by mail, a process that could take weeks. Nowadays, many of these documents are instantly available.

Prall has developed a routine to vacuum up mug shots. Using a polite tone, he demands that local police departments provide him photos. If that fails, he drafts appeals and complaints to supervisory state boards. His relentless requests irritate many. “I deal with a lot of distasteful people, and he's right at the top of that list,” says Les Moore, legal adviser to the Irving, Texas, police department. “This guy's been a pain in my backside for a number of years.”

Bustedmugshots.com

tells visitors that it is “a valuable asset to local law enforcement” that has led to breakthroughs in crime investigations. Many local officials disagree. They object to the site's profit motive. And though they do not show much sympathy for the lawbreakers in their jails, they do not necessarily believe in public shaming either. Mostly, however, they don't believe the site offers much of a public service.