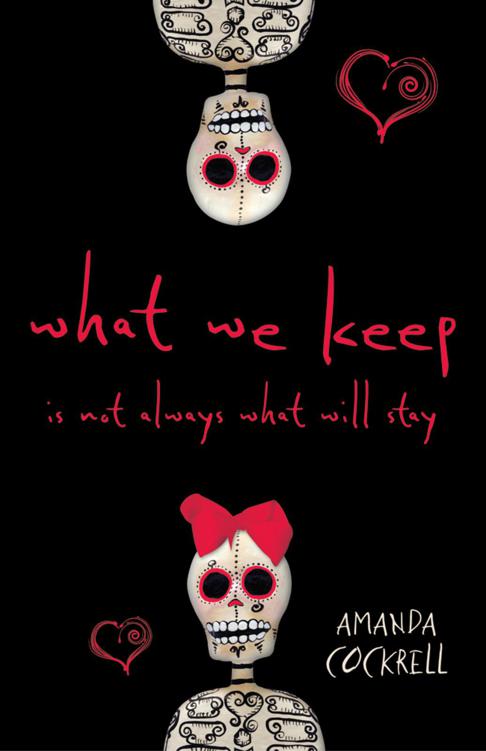

What We Keep Is Not Always What Will Stay

Read What We Keep Is Not Always What Will Stay Online

Authors: Amanda Cockrell

Woodbury, Minnesota

Copyright Information

What We Keep Is Not Always What Will Stay

© 2011 by Amanda Cockrell.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Flux, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author’s copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Cover models used for illustrative purposes only and may not endorse or represent the book’s subject.

First e-book edition © 2011

E-book ISBN: 9780738728940

Cover design by Kevin R. Brown

Cover images: Day of the Dead figure © iStockphoto.com/Luis Sandoval Mandujano;

heart © iStockphoto.com/Artur Figurski;

bow © iStockphoto.com/Donna Coleman

Flux is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Flux does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher’s website for links to current author websites.

Flux

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.fluxnow.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Tony and the original Felix

1

I am not a religious fanatic. I want to say that right off. It’s just that ever since I got lost looking for the bathroom at church when I was little, and found a statue of St. Felix down in the basement, I’ve talked to him.

He’s down there because we aren’t supposed to pray to him, since he’s one of those saints the modern church thinks might have been just a product of somebody’s imagination, which is embarrassing if you’ve been asking him to intercede with God for you. But he looked, I don’t know, friendly. Like someone I could tell things to. I’m fifteen now and I’ve been talking to him since I was nine. He’s life-size, and has gray hair and a gray beard and a kind of white gown with maybe a red and blue cross on the front, but he’s really faded and you can’t tell for sure. The name “Felix” is carved into the base, by his feet. I looked him up in a

Lives of the Saints

book and I think he’s Felix of Valois, but he might be one of the other Felixes—there have been lots, some of them even more dubious than Felix of Valois. Nobody knows where the statue came from. It looks hand-carved, and some early parishioner probably made it. Nobody pays any attention to him now. I dust him once in a while, while I talk to him.

He’s like having a diary in invisible ink. From my lips to his ear, as my grandfather says, and no one can ever read what I’ve written. I told him when Noah Michalski tried to put his hand up my shirt at a church dance and then told the entire planet I’d

let

him, which I hadn’t; and when my cat died; and when my mother decided she was going to divorce Ben, who’s a perfectly good stepfather that I’ve had since I was eight.

“Ben says Mom will come around,” I told Felix. I leaned against the dusty old wall and picked paint flakes off it. There was more dust dancing around in the light from the window over his head, like an extra halo. “Mom gets like this every summer,” I told him. “Like she wants to migrate or something, and then she settles down in the fall. But I don’t remember her ever being this bad.” Usually she just goes to Big Sur for a week and writes poetry. Mom teaches English at Ayala Middle School, where they all think she’s terribly cool because she has this head of wild red hair and wears arty clothes. I look a lot like her, except for having dark hair and my dad’s Latino coloring, but for some reason all that wild hair that looks arty on her just looks dorky on me.

“I told Mom that Ben is the nicest guy I know,” I said to St. Felix. “And she said you can’t stay married to somebody just because they’re nice.”

St. Felix looked sympathetic. I flopped down on the floor at his feet, poking with a finger at his carved sandals. “I remember when they got married. I was the flower girl. I had a big basket of rose petals.” I looked up at St. Felix. “People are supposed to hate their stepfathers. I

like

Ben. He’d probably have adopted me if we could have found my real father and proved he’s dead. You’d think my mother would want to set me a good example. How am I supposed to find a boyfriend with an example like that?”

I poked at his sandal some more. “I haven’t spoken to her since she said she was leaving Ben and we had a big fight over it. I don’t know how long I can hold out. It’s not easy not talking to your mother.” It felt good to tell someone that, even a statue, since I couldn’t say it to Mom if I wasn’t speaking to her.

And then, the next day, Mom moved out and went to my grandparents’ house. For a whole week now she’s been calling and pestering me to move there with her. I’m still living at Ben’s. Ben’s house is where I’ve lived since I was eight, and I’m not going anywhere. I’ve managed to hold out not speaking to Mom, too pig-stubborn to say one word to her when she tries to talk me into going to my grandparents’ house. Then she orders me to come, then threatens to call the police and have them

bring

me there. I’m mad, but I’m sort of enjoying how nuts it’s driving her.

She finally came over here to argue about it some more while Ben and Grandma Alice and I were having dinner. Grandma Alice is Ben’s mother, and she moved in with us last month, not long before Mom moved out. Grandma Alice offered to move out again but Mom said that wasn’t the problem, she would rather have Grandma Alice than Ben. She said it right in front of him, but he just grinned at her. Grandma Alice says there may be things I don’t know.

So Mom walked into the dining room as if she’d never left and started talking to me while I was buttering my potato. “Angela, I am your mother, and I will make the decisions as to what is best for both of us. You need to stop behaving in this childish fashion.”

No, I don’t,

I thought.

You need me to.

I cut my potato into tiny little bites, which Mom hates because she read somewhere that it’s a sign of an eating disorder—which I don’t have, but which she thinks I might develop at any moment, like a pimple on my nose.

“Sylvia,” Grandma Alice said, “maybe it’s best to let Angie have a little time.”

“No reason she can’t stay here,” Ben said, spearing another piece of steak.

“Of course she can’t stay here,” Mom said.

I got up while they were arguing and took my plate to the kitchen, and then went out the back door before Mom noticed. I figured I could get several blocks away before Mom got around to wondering why I was still in the kitchen.

Our house—well, Ben’s house—is right downtown. It’s not much of a town. There’s only one stop light. I ducked under the big live oaks that shade the library and jaywalked across Ayala Avenue to my church, St. Thomas Aquinas. It isn’t one of the famous California missions that Father Serra founded, but it’s almost as old. I like it lots better than the new church Mom goes to. It’s always cool and dim at St. Thomas’s, even if Mom does think it has mice. It smells like incense, and the adobe walls and the stations of the cross are all dark from the candle smoke.

It was dusk when I headed out and St. Thomas’s was dark inside, just the glow of the candles in the chapel that people light to thank the Virgin for something, or to ask her to keep their husband safe in the army or make him faithful or let them win the lottery. I skirted by them, thinking maybe on the way out I’d light one for Mom to get some sense.