Wheel of Stars (11 page)

Authors: Andre Norton

“He's young—no tellin’ ‘bout him,” Mel commented. “He's already stayin’ up at the house. Saw him goin’ down the lane last night. Friendly enough seemin’, I guess, but he ain't like the Lady. She was one to keep to herself maybe, still there's never any need she hears of that she doesn't lend a hand in helpin’ out. You can ask the Reverend about that. Too bad he couldn't make the meetin’ today. Heard tell that Sally Edwards was taken ill so he undertook to drive her to Freeport—”

“What's wrong with Sally?” Mrs. Kitteridge showed even more animation. “Why, I met her in town just two days ago and she looked as good as ever. Said she had nothin’ to complain about either. Was it some sort of accident? Why didn't we know?” Her indignation grew with every word.

“No accident,” Mel shook his head. “Think the family don't want it talked ‘bout—but it'll be all over town sooner or later anyway. Sally was found at the edge of Brink's Woods near clean out of her mind—real hysterical she was. Then her heart took a bad spell. They figured they had to get her to the hospital as soon as they could. We need us a doctor in this town. Ever since old Doc Anderson died, we've needed one. But these here young fellows nowadays—I guess they figure they can make a lot more money in the cities, and there're too few of us to give them that kind of a livin’. Maybe we're just all too healthy for our own good.”

“Brink's Woods—” Jim, who was generally

keen on the subject of trying to attract medical aid for the town, was more interested in the other part of Mel's report. “That's on the other side of the Lyle place, isn't it? I was thinking when I drove by there just the other day that it was unusual there hadn't been any logging done there for so long. Lots of dead stuff ought to come out—a dry summer and a lightning strike there—then we might find ourself with a real fire.”

“True enough. But you ain't goin’ get old Lovey Brink to do anything ‘bout it. She couldn't care less, long as she has her garden patch and her check comin’ in regular at the bank. Her son ain't been home in ten years or more. Brink's Woods—you know that is a place that devil critter, whatever it is, might well take to hide out in. And were a woman like Sally to maybe be chased, or even see something strange, she could well have a heart attack. I think Baines ought to look a little in the direction and I'm goin’ to tell him so. Well, time to be gettin’ ‘long. We got some things settled anyhow. Gwen, you watch out for the pennies now. They mightn't go far these days—but they aren't to be thrown around carelesslike neither!” He heaved his bulk out of the chair.

For the first time Gwennan realized that Mr. Stevens, though he had been present, had had very little to say. He had even pushed his chair a little away from the table, making only absent-minded comments when he was called upon. There was a briefcase leaning against one of the legs of his seat, but he had never reached for it, though she had expected him to produce something pertinent to library affairs. Instead he had

steepled his fingers together and more or less fixed his attention outwardly on them, as if his patience was being strained to wait out the conclusion of the meeting.

She ushered the rest of the board out, assured Jim Pyron he could have ready access to the Crowder papers whenever he wished, and returned to where the lawyer waited for her.

“There is bad news.” He greeted her. “Lady Lyle is dead.”

Said so bluntly, it shocked her, yet part of her had been prepared. The pendant which she now wore within her blouse—that could not have come to her had its former owner still been alive.

“I—I am sorry. She was kind to me.” Gwennan used those words said so often. They did not express the depth of what she really felt, but they were the ones expected from her.

“She knew that she had very little chance of returning when she went—I have since learned. Before she did go she left this with me—to be given to you.” He opened the briefcase to bring out a large envelope. “What did Miss Nessa ever tell you about your parents?” His abrupt change of subject surprised her.

“My mother was Miss Nessa's half-sister, but she was much younger. She went to college, working her way. Miss Nessa did not approve. Then she met my father before she had finished her second year, and they were married very suddenly. Miss Nessa disliked that also—she believed in finishing whatever one had once begun. My father—I don't really know what business he was in, but they traveled all the time. I was born

abroad, somewhere in South or Central America. I saw the papers once—they are at the bank in Freeport now. But my parents registered me with the nearest American Consul and I am an American citizen. They brought me back here the next summer. After that we went to India and—But I do not remember very much of that.

“When I was old enough for school they returned here again before they went to the southwest and were killed. It was one of those freak accidents you read about when a plane is missing—like the Bermuda Triangle.

“Then I just stayed on with Miss Nessa and as you know I've lived here ever since.”

“But you took the name Daggert. What was your true name?”

Gwennan flushed. “I—I don't know. Miss Nessa entered me in school under her name—told me that it was mine now. I always wondered if my mother had not married some distant family connection whom Miss Nesssa had not liked.”

“I think that it was a very different name,” he pronounced that as if it were a judgment. “Lady Lyle had a distinct interest in you from the first—though she never revealed it to you directly until lately. I know she asked for reports concerning you—sometimes writing from other parts of the world. Though she never explained why she wanted them. You know that the Lyles, though there have never been more than one or two to appear here in a single generation, do have connections elsewhere. When they married it was always away from home, and within the ranks of their widespread family, choosing a branch

sometimes from another country. It may be that your father had Lyle blood. That would be an excellent reason for Miss Nessa to keep your relationship, as she thought, secret.”

“But why?”

“Miss Nessa was a very proud woman. It could be also, and do not mistake my motive in saying this, Gwennan, that she did not consider, for some reason, that the marriage was a legal one. Miss Nessa, as we both know, clung very closely to the manners and morals of another generation. If your mother was not married openly here in the church, to a man well known to the community, Miss Nessa might deem the union to be a dubious one.”

He was right, as Gwennan knew. But one of the Lyles—what had Tor called her in the tempestuous interview—a half-blood! Only his taunt was no evidence. Perhaps the envelope she now held would provide that.

She tore it open. Mr. Stevens was buttoning his coat. He nodded to her.

“If there is anything in there which you believe needs legal handling, do not hesitate to come to me, Gwennan. There are matters now to be settled concerning the estate. I suppose this young man gets everything—he seems to be the heir Lady Lyle acknowledged, to the extent of bringing him here before she left.”

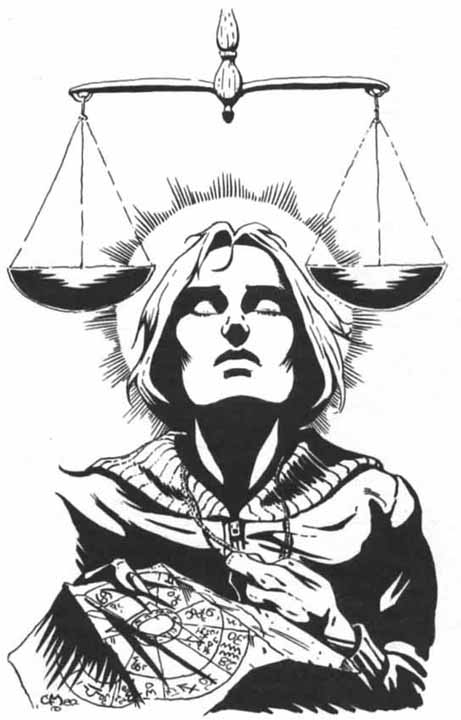

He went out as Gwen sat down slowly at the table. What she pulled out of the envelope was a sheet of stiff paper on which was an intricate drawing. With that fluttered a page of much lighter and thinner weight. The larger sheet was,

she recognized from her reading, a very detailed astrological chart, but she did not know enough about the subject to interpret it for herself. Only there was a birthdate printed at the top and it was her own. Plainly this must be intended for her—for a reason she could not understand.

She picked up the second page which had accompanied it. The writing was very clear and bold, resembling the printing on the chart, yet possessing the individuality of hand script. It was Lady Lyle's.

“My time is much shorter than I had hoped it would be. My body functions have been tampered with in an obscure manner, and I believe I know the reason. Therefore I have not the full chance to pass to you what should be part of your knowledge. You will have to learn for yourself, in that learning you shall grow—for doors open when you knock. Within will lie many things you have forgotten or which were purposefully reft from you. What you were meant to be was once changed—”

“Ortha—” Gwennan whispered. “She must be speaking of Ortha!”

“The old knowledge, the control of power which was your right, was drained from you, so that you come lame into the land of the free. What only can be done is to give you the opportunity to relearn, to strengthen, to so approach the person who you were meant to be. I shall leave you the key—also a certain other tool. But I am able to extend you no protection.

“What you do you must learn for yourself, choose for yourself—that is the Law of the Power. We are free in that much. There are always choices before us. When we make those we alter our lives, and sometimes the lives of others, one way or another.

“The stars have returned to old courses, for so do the heavens circle with generation upon generation between. Once more they stand as they did when you were born before—to be plundered of what was to be yours. You again may choose.

“This much I lay upon you. At Midwinter Day go to the standing stones and there use the watch of the star hours as instinct moves you. What will thereafter follow will provide your testing choice. I wish you very well—you have that in you which was meant to draw us close. And, the Power willing, it shall again.”

Just as there had been no salutation on the letter, so there was no signature. Lady Lyle might have written so that what she had to say would remain a puzzle to hostile eyes. Only the date on the horoscope assured Gwennan that what she held was meant for her alone. But

what

it meant she had yet to learn.

Gwennan sat at the kitchen table, the only surface large enough in the house to hold the burden of papers and books she had so carefully been able to assemble. A little of her experience by the standing stones had been time dulled. It was days—weeks—since that night which had made her aware of more than one world—painfully and completely aware. There had been no further sign from the new master at Lyle House. In fact Tor Lyle might have disappeared as completely and finally as his kinswoman as far as Waterbridge was concerned.

Nor had there been any more traces of the “devil.” Jim Pyron delved into the Crowder papers and came up with enough odd tales of village history to furnish him with his proposed column. In fact he made a habit at present of dropping in at the library on Saturday mornings for research. Gwennan found his discoveries and opinions concerning them interesting enough, but it was her own private reading which occupied her evenings and as much time as her conscience

would allow her to spare from regular duties.

Miss Nessa's house suffered no thorough weekly cleanings these days. If the bed was made and the dishes done, the worst of the dust smacked away in the two rooms which had come to center Gwennan's life, she decided she had spared time enough. The reading was more important.

She longed for intelligent and trained help, and knew nowhere to seek or ask for such. The chart of the stars remained a closed secret to her, no matter how much she sought out explanations in the various astrology books she gathered and pored over. Mathematics had always been a defeating study for her, and these all drew upon an esoteric form of that science.

There remained the stones themselves and the ley lines. She had ordered, through loans, everything possible on the subject. Now the mass of assembled but hardly correlated material engulfed her with piles of notes. There existed all over the world large and small stones, some with holes fashioned in them. Some such were thought to heal; the afflicted person, an ailing child could crawl or be passed through such a hole to be cured. There were other holes which seemed to be sacred places where one swearing an oath set his hand to ensure his loyalty to a bargain. There were cups hollowed in stones in which lay pebbles which needed only to be turned to ensure either good fortune or an efficient cursing. There were stones upon stones upon stones!

Stones which moved, according to old legends,

upon certain days of the year or at night. Stones which were said to be sinners turned forever into rock to suffer for their various crimes, stones which the devil had tossed spitefully at sacred places, only to have his bombardment fall short, or else be turned aside by the equal power of some saint. It would seem from her now feverish reading that England, in fact all of the British Isles, was completely paved with stones possessing one form of “magic” or another. And that was just England!

There were the stones of Brittany and others scattered over Europe, though the legends concerning those had not been so carefully kept or gathered. Then one turned to South America. What of the single mountain there covered with carvings which no modern archeologist or artist could account for or understand—strange beasts—the head of a man which showed as that of a youth in the morning and slowly aged during the day as the light changed and moved across it, a whole mountain which was a monument to a nation or people completely lost—whose work was to be found nowhere else in the world.

Gwennan compiled reams of lists—marked over maps. She became inundated with utter chaos, bewildering more than instructing her. Now and then, looking upon some photo illustration in a book, or coming suddenly on a scrap of legend, she had a flash of thought which might almost be a scrap of memory—but certainly no memory of her own! She knew that theory of folk memory also—of a storage of ancient learning which could be touched and drawn upon by the

far descendants of one who had lived or seen—

Many lives? Was that the answer? Did some personal essence travel away from a vast parent identity, incarnate in order to learn—to expand certain attributes—live so as a separate entity, to return eventually to the source? Had she indeed been once a temple seer named Ortha in a civilization so devastated by worldwide disaster that it was totally forgotten?

Those who had passed through, had survived such an overwhelming of the land, the rolling of the sea as she had witnessed before the Mirror—yes, those might emerge with a madness in them walling away the full memory of what had been. Reduced to wanderers—thrown back into a time when stones were tools and man could turn against man for a scrap of food, a place of safety for a night—how long would they hold in mind, except as unbelieved stories, what they had once been?

And there

were

such legends—from India, from many native peoples who trained memories rather than trusted to written documents and scientific forms of retaining knowledge. What of that obscure and primitive tribe in Africa who know well the orbit of Sirius and worshipped it? What of the worldwide tales of survival from a great flood—men, women, a few animals saved—some on ships, rafts, some crawling out from mountain caves, to face an entirely new world? She had them here—those stories as they were now reported, printed, open to the reader who wished to speculate on the strangeness of imagination which stretched worldwide—save what if

such were NOT born of imagination at all?

Gwennan's pack of papers grew. She compiled from all she could find those facts which were pertinent to what she had seen, experienced during that single night. And, though she would not have admitted the fact to any, she believed in the truth of Ortha's world, and in the existence of the ley lines.

There had been no more reports of the “Devil.” With the disappearance of Tor from sight the night prowling monster seemed also to have taken its departure. The girl no longer doubted that it

was

Tor who had somehow, willingly or even unknowingly, summoned the thing.

There were many tales of such which had appeared and disappeared — either in electrical storms or along the ley lines. If those were indeed sources of a power as strong as any man's efforts had been able to generate and which the stones gathered, or transmitted, why

could

not that unknown power, wrongly used, or uncontrolled, open gates into other places of existence? She had now hundreds of accounts of monsters which had appeared, had devastated and killed, or merely frightened, had been slain, or had simply disappeared. The knight and the dragon in conflict—was that the remainder of a very ancient real happening—outworld things faced down by one who had the Power?

She was feverishly intent on what she tried to learn, what some driving compulsion within her said

MUST

be learned. Only now and then her Miss Nessa trained good sense clamped down. So far she

had

managed to keep her absorption with all

these studies apart from her every day life, and, since she had never been very socially inclined, no one suspected what she so feverishly sought.

Now she leaned back in her chair to survey the pages of notes she had compiled out of all the books and clippings which littered the table, or had littered it and been discarded, during the past weeks. These—she laid her hand firmly down, pressing on the papers—were the only answers she could find in all her searching. And they remained so vague, so few. Even strung together as tightly as she had tried to put them, they were not evidence any other person in this town would consider as meaningful. There were other places in the world—there were all the writers of the books she had consulted—they had in them belief that things were not as they had always been told or they would in turn not have gone seeking. For the first time in her life Gwennan considered the idea of traveling—of trying to make contact with some other of these seekers.

Considered—and knew that it was impossible. She had never had any wish to leave Waterbridge. Now she discovered such a suggestion aroused more than just a tinge of uneasiness in her—she shrank from the thought entirely. It was as if she must remain here waiting—

Lady Lyle's letter—she had read it many times over—had told her to seek and certainly that was just what she had been doing. Yet what concrete facts might she learn from this collection of folklore, speculation, guesses—some of them wild enough? Space men who had landed long ago to

father a new race upon half human beings, men and women whose powers had deified them among their fellows, lost cities deep in jungles, vitrified patches in desert lands which might possibly mark ancient atomic disasters, the news that the moon overhead was far older than man had believed, that there might be two other planets always hidden—the dark moon Lilith—the sun-washed Vulcan—

None of this was of much use to her. Gwennan was suddenly tired, as if the fatigue gathered through the hours of her searching settled upon her all at once. Now she slumped a little forward, her head in her hands. Her eyes smarting from all that feverish reading, closed. What

was

the sum total of what she had learned? Nothing of any value.

She had not returned to the standing stones since that morning when she had fled their mound. Nor would she go—not there! Now she raised her head and looked to the old desk where Miss Nessa had kept, in small neat packets (each fastened with a rubber band or tucked into an envelope) those few papers which to her had importance. There was the deed to this house, tax receipts for many years, some receipted bills, the insurance papers. Nowhere was there anything pertaining to Gwennan except her own birth certificate, the paper signed by a consul in a foreign land proclaiming her American, the child of American citizens. She had hunted through all that hoping to uncover a marriage certificate stating her father's full name, something of her past. If there ever had been any such Miss Nessa

had deliberately disposed of it.

Until Mr. Stevens had asked her Gwennan had even forgotten that her name was not her own. She had sought for that certificate upon her arrival home that day—

Ketern—certainly an odd name—one bearing no resemblance to any family hereabouts.

NOT

Lyle. The lawyer's hint of that had been a mistake.

She was so tired. A glance at the watch on her wrist gave her a start. It was after twelve. She would awake stupid and unready for work if this kept on. Mechanically the girl gathered her papers into a pile, put the books into order. However, though she stood up—she did not at once go to bank the stove.

There was a howl of wind tonight. The first snow had fallen three days ago and there was talk she had heard in the library of a bad storm on the way. This evening, before Gwennan had sat down to study she had made sure there was a good supply of wood to hand. And she was wearing three layers of sweaters now. There were storm supplies in the cupboard straight ahead—a prudent laying up of what every householder needed in a season when one could be snowed in.

Tomorrow was Saturday—another half day at the library. But that did not mean that she was excused from opening up, unless a blizzard closed the roads tonight.

Gwennan went to the window and looked out. There should have been a moon, but clouds hung heavy, and there was the steady hiss of falling flakes against the pane on which frost was al-

ready building a veil.

She made her preparations for the night slowly, loath to leave this room which was always the warmest of the old house, almost deciding to bring in bedding and spend the night on the sofa as she had done in the past. But at length she hurried through the process of going to bed. Only, tired as she was, sleep did not come.

Instead she found that her eyes were continually drawn to the frost paned window through which that thing of the Dark had watched her on the night of the storm. Would the cold ward off any such which might stray through between the leys?

If

that thing had so come, and now she believed that that much was the truth.

Under the mound of covers she clasped the pendant. That she had kept always with her—even though she hid it beneath her clothing. It was made of a metal she could not name, for, though it had a silver sheen, she did not believe it

was

silver—it was never cold. Rather was a small core of reassuring warmth always to answer her touch.

The watch of the Star Hours, Lady Lyle had named it. However, since Gwennan had left the vicinity of the stones that morning the symbols became so dim they could only be seen in the strongest light. While the bar which had moved about the dial disappeared from sight entirely. To take it to the stones at Midwinter day—almost a month away still. Did she want to go—perhaps to plunge into another series of adventures which would separate her even farther from her own birth world?

Yet to cup the watch as she did now between the palms of her hands and her own breast gave her such a feeling of security as she might have had if some friend stood beside her shoulder to shoulder. She closed her tired eyes upon the dark of the room.

Cold—tight—

Did she walk, run, or was she borne in some fashion above that long ribbon of light? There arose a wall of dark on either side, so thick, in a way so menacing, that she knew only with the light she followed was there safety. Now from that narrow path arose tendrils of mist—some pure white, some tinged with gold. Those close to her were only streamers—yet it seemed that those farther ahead formed tenuous figures and shapes—only to melt as she approached.

There was a pyramid. She might have been viewing the huge structure from a far distance. From its sides streamed tongues of light as those ribbons had once curled from the fingers of the Voice when she wove her peace and harmony spells. Then, as Gwennan floated the nearer, the pyramid vanished. A wheel arose in turn, to stand before her as might a barrier refusing her passage. Within its rim glowed a five-pointed star and where each point touched the outer circle a ball of light gave new source to the floating ribbons of Power.

The wheel faded, was gone. What waited ahead now was a symbol she knew well—part of those same half-effaced markings carved above the doorway of the house which she claimed as her own. This was the ankh—the key—and from loop

above, arms below, always the light—