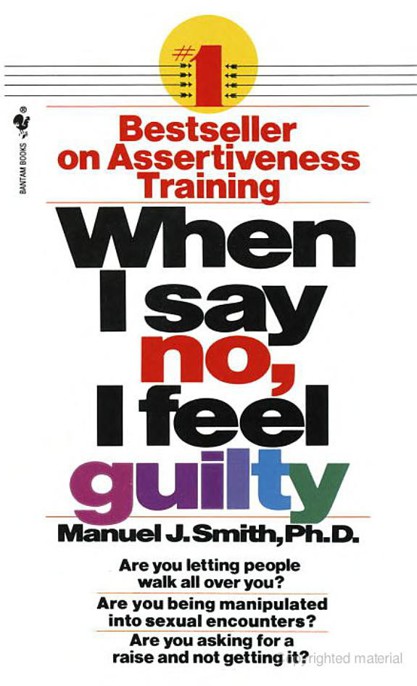

When I Say No, I Feel Guilty

A BILL OF ASSERTIVE RIGHTS

I: You have the right to judge your own behavior, thoughts, and emotions, and to take the responsibility for their initiation and consequences upon yourself.

II: You have the right to offer no reasons or excuses for justifying your behavior.

III: You have the right to judge if you are responsible for finding solutions to other people’s problems.

IV: You have the right to change your mind.

V: You have the right to make mistakes—and be responsible for them.

VI: You have the right to say, “I don’t know.”

VII: You have the right to be independent of the goodwill of others before coping with them.

VIII: You have the right to be illogical in making decisions.

IX: You have the right to say, “I don’t understand.”

X: You have the right to say, “I don’t care.”

YOU HAVE THE RIGHT TO SAY NO,

WITHOUT FEELING GUILTY

Bantam Books of Related Interest

Ask your bookseller for the books you have missed

CHANGE YOUR MIND, CHANGE YOUR LIFE by Gerald Jampolsky FIRE IN THE BELLY: ON BEING A MAN by Sam Keen

IF YOU MEET THE BUDDHA ON THE ROAD, KILL HIM! by Sheldon Kopp LOVE IS THE ANSWER by Gerald Jampolsky

MEN WHO HATE WOMEN AND THE WOMEN WHO LOVE THEM by Susan Forward PASSAGES by Gail Sheehy

THE POWER OF YOUR SUBCONSCIOUS MIND by Dr. Joseph Murphy HONORING THE SELF by Nathaniel Branden

HOW TO RAISE YOUR SELF-ESTEEM by Nathaniel Branden THE SIX PILLARS OF SELF ESTEEM by Nathaniel Branden

NOT ONE WORD HAS BEEN OMITTED.

WHEN I SAY NO, I FEEL GUILTY

A Bantam Book / published by arrangement with

The Dial Press

PUBLISHING HISTORY

Dial Press edition published January 1975

Bargain Book Club edition / December 1974

Literary Guild Book Club edition / June 1975

Bantam edition / November 1975

All rights reserved

.

Copyright © 1975 by Manuel J. Smith

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or

by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing

from the publisher

.

For information address: Bantam Books

.

eISBN: 978-0-30778544-2

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Random House, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, 1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036

.

v3.1_r4

To Mankind,

the one animal species

I truly care about,

and its following members:

Dennis

Evelyn

Fred

Gladys

Hal

Ian

Irv

Jennie

JoAnn

Joe

Mannie

Phil

Sue

and

The Turk

The author wishes to acknowledge the work of Dr. Bruce Leckart towards formulating the concepts and writing the first draft of this manuscript.

Preface

The theory and verbal skills of systematic assertive therapy are a direct outgrowth of working with normal human beings, trying to teach them something about how to cope effectively with the conflicts we all have in living with each other. My initial motivation for developing a systematic approach for learning to cope assertively began with my appointment as a Field Assessment Officer at the Peace Corps Training and Development Center in the hills near Escondido, California, during the summer and fall of 1969. During this period, I observed with dismay that the traditional techniques—fancifully known as the “armamentarium”—of the clinical psychologist (or of any theraputic discipline for that matter) were quite limited in that training setting. Crisis intervention, individual counseling or psychotherapy, and group process including sensitivity training or growth-encounter group methods did little to prepare relatively normal Peace Corps trainees for coping with the everyday human interaction problems that most veteran volunteers had met overseas in their host countries. Our failure to help these enthusiastic young men and women became apparent after twelve weeks of intensive training and counseling when, for example, they were given their first dry-run demonstration of a portable insecticide sprayer. Squatting on their heels in a dusty field to simulate a group of rural Latin American farmers were a motley bunch of PhDs, psychologists, a psychiatrist, language instructors, and veteran volunteers dressed in straw hats, shorts, sandals, GI boots, tennis shoes, or bare feet. As the trainees proceeded with their field demonstration, the ersatz farmers showed little interest in the insecticide sprayer and great interest in the strangers coming to their village fields. While the trainees could adequately answer questions on agronomy, pest control, irrigation, or fertilization, not one gave a believable answer to questions that

the people they wanted to help would probably ask first: “Who sent you down here to sell us this machine? Why do you want us to use it? Why do you come all the way from America to tell us this? What’s in it for you? Why do you first come to our village? Why do we have to grow better crops?” And so forth. As each trainee tried, in exasperation, to talk about the insecticide sprayer, the ersatz farmers kept asking questions about the trainee’s reasons for coming to them. Not one trainee, as I recall, assertively responded with something like:

“Quien sabe

… Who knows the answers to all your questions? I don’t. I only know that I wanted to come to your village and meet you and show you how this machine can help you grow more food. If you want to grow more food, maybe I can help you.” Without such a

nondefensive attitude and assertive verbal response

when they found themselves in the

indefensible

position of being interrogated for suspicious motives, most of the trainees had an unforgettable, embarrassing experience.

While we had taught them adequate language, cultural, and technical skills, we had not prepared them at all for assertively and confidently dealing in public with a critical personal examination of their motives, wants, weaknesses, even their strengths—in short, an examination of themselves as persons. We had not taught them to cope in a situation where the trainee wanted to talk about agronomy and the ersatz farmers (as the real

campesinos

would) wanted to talk about the trainee. We had not taught them how to respond in such a situation because we didn’t then know what to teach them. All of us had vague ideas about the situation but none of us helped much. We did not teach the trainee how to assert himself without having to justify or give a reason for everything he does or wants to do. We had not taught the trainee how to say simply: “Because I want to …” and then leave the rest up to the people he was going to try and help.

In the few weeks remaining before they took their oaths and departed, I experimented with all sorts of theraputic training variations and improvisations with

as many of the trainees as were receptive. As the final week drew nearer, the number of trainees who avoided me grew. None of the ideas off the top of my head showed any results then or even any promise, but I did make one important observation: the trainees who coped least well with critical personal examination behaved, in dealing with other people, as if they could not admit failure—they seemed to feel they had to be perfect.

This same observation was made again during my clinical appointments in 1969 and 1970 at the Center for Behavior Therapy in Beverly Hills, California, and at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Sepulveda, California. In treating and observing patients whose diagnoses ranged from normal or mild phobias to severe neurotic disorders, and even with schizophrenics, I found that many of them had the same inadequacy in coping as did the young Peace Corps trainees, although to a much greater degree. Many of these patients seemed incapable of coping with critical statements or questions about themselves from other people. One patient in particular showed such a marked resistance to talking about anything to do with himself that four months of traditional psychotherapy produced only a few dozen sentences from him. Because of his mute withdrawal from other people and his obvious anxiety at being around other people, he was diagnosed as a severe anxiety neurotic. On a hunch that he was simply an extreme case of the Peace Corps trainee syndrome, I switched from “talking” about him to talking about the people in his life who gave him the most trouble. Over a period of weeks, I learned that he was both terrified of and hostile toward his stepfather, a person who related to him in one of two ways—he either criticized or patronized. Our young patient, unfortunately, knew no other way to relate to his stepfather except as the object of criticism or patronage. Consequently, in the presence of this authority figure, the patient was all but mute. His almost involuntary silence, produced by his fear of being criticized and his knowledge that he was unable to defend himself, became generalized and was

employed with anyone else who had the least amount of self-assuredness. When I asked this fearful young man if he would be interested in learning how to cope with his stepfather’s criticism, he began to talk to me as one person to another. We worked experimentally on

desensitizing him to criticism

from his stepfather, his family, and people in general Within two months, this “mute neurotic” was discharged, after leading a group of other young patients out on a drinking spree and then generally raising good-natured hell on their ward when they returned. At last report, he was enrolled in college, dressing as he pleased, doing much of what he wanted to do in spite of any protests from his stepfather, and with a good prognosis of not being rehospitalized.

After this successful but novel treatment, Dr. Matt Buttigtieri, Chief Psychologist of the Sepulveda VAH, encouraged me to try these treatment techniques with similar patients and to develop a systematic treatment program for nonassertive people. During the spring and summer of 1970, the assertive therapy skills described in this manuscript were clinically evaluated both at the Sepulveda VAH and at the Center for Behavior Therapy with that master clinician and colleague, Dr. Zev Wanderer. Since that time, these systematic skills have been expanded and used by myself, my students, and my colleagues to teach nonassertive people how to cope effectively with other people in a variety of settings. These assertive skills have been taught in university, county, and private outpatient clinics, university training programs and classes, graduate and undergraduate psychology programs, weekend training seminars, and professional workshops, as well as in probation, social welfare, prison, rehabilitation, and public school training programs, and the results have been reported on in professional meetings.

Whether we choose to call the people who can benefit from systematic assertive therapy everyday people who have difficulty in coping verbally with others, as in the case of the Peace Corps trainees, or neurotic, as in the case of the young “mute” patient, is to me irrelevant.

What is relevant and important is learning how to cope with life’s problems and conflicts and the people who present them to us. That, in a nutshell, is what systematic assertive therapy is all about and why this book was written. The assertive skills described in this work are based on five years of my own and my colleagues’ clinical experiences in teaching people to cope. By writing about the theory and practice of systematic assertive therapy it is my aim to help give as many people as possible a better understanding of what often happens when we feel at a loss in coping with one another … and what we can do about it.

M.J.S.

Westwood Village

Los Angeles

Acknowledgments