When the Astors Owned New York

Read When the Astors Owned New York Online

Authors: Justin Kaplan

LSO BY

J

USTIN

K

APLAN

Walt Whitman: A Life

Lincoln Steffens

Mark Twain and His World Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain

W

ITH

A

NNE

B

ERNAYS

Back Then

The Language of Names

USTIN

K

APLAN

When the Astors Owned New York

B

LUE

B

LOODS

AND

G

RAND

H

OTELS

IN A

G

ILDED

A

GE

VIKING

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand,

London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell,

Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue,

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park,

New Delhiâ110 017, India

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany,

Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Electronic edition: April 2007

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-1012-1881-5

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights is appreciated.

Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

To Annie, as ever

ONTENTS

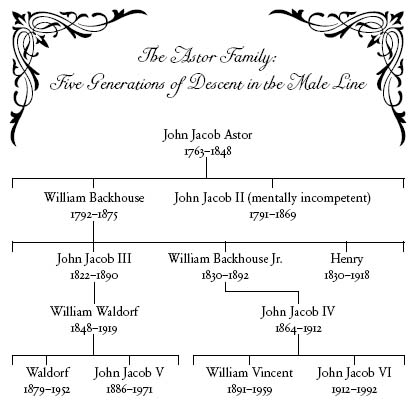

L

ike English royalty and with comparable pride, the Astors drew on a tiny pool of only a few names to mark and continue their succession. Within the compass of the present narrative, descent in the male line was as follows: John Jacob Astor, the founder, begat William (Backhouse), who begat three sons, John Jacob III, William Jr., and Henry. The eldest of these three sons, John Jacob III, begat another William (Waldorf ), who in turn begat John Jacob V. William Jr., meanwhile, begat John Jacob IV, who begat yet another William (Vincent) and John Jacob VI. John Jacob II, the founder's other son, was mentally incompetent and had no part in the succession. Henry Astor, his nephew, was virtually expelled from the family after he married a farmer's daughter.

W

HEN THE

Titanic

went down in the North Atlantic on the night of April 14â15, 1912, she took with her John Jacob Astor IV. He was forty-seven years old and coheir, with his first cousin, William Waldorf Astor, to a historic American fortune. Colonel Astor, as he preferred to be known, had been traveling with his nineteen-year-old bride, the former Madeleine Talmage Force, who was five months pregnant.

When the ship began her fatal list to port, Astor helped his wife into a cork jacket, led her to a lifeboat, and waved to her from the deck as it was lowered away. “The sea is calm,” he assured her. “You'll be all right. You're in good hands. I'll see you in the morning.” In obedience to the women-and-children-first law of the sea, he remained on deck and, according to some reports, later repaired to the ship's smoking room for a game of cards. A fellow passenger, J. Bruce Ismay, managing director of the White Star Line, the ship's owner, had jumped without hesitation into the first available lifeboat and rowed away with other survivors.

Astor was probably crushed by debris or a falling smokestack as the

Titanic,

her stern high in the air, sank by the head. A week or so later, a passing steamer, the cable ship

Mackay-Bennett,

picked up Astor's body, floating erect in his life belt, with his gold watch and $2,500 in bills still in the pockets of his blue suit, and delivered it, along with about two hundred other corpses packed in ice in rough coffins, to Halifax. The Prince of Wales sent roses to Astor's funeral at Rhinebeck, New York, in May. The following January a merchantman, traveling along the west coast of Africa, picked up a broken deck chair from the

Titanic

on which one of the victims, whom subsequent myth has held to have been Astor, a devout Episcopalian, had scratched with a penknife the words “We will meet in heaven.”

In his earlier years Jack Astor had earned a reputation as a spoiled lordling, deficient in grit and charm; a failed (and abused) husband whose miserable first marriage had ended in a divorce with an admission of adultery on his part. He had also been a public fool on more than one occasion. Although awed by his wealth, reporters who delighted in following his career dubbed him “Jack Ass.” His public rehabilitation had begun during America's war with Spain in 1898â1899. He lent his 250-foot steel yacht

Nourmahal

to the navy, donated a battery of howitzers to the army for use in the Philippines, outfitted and drilled his own “Astor” company of artillerymen, and acquired a commission. He saw brief service in the field in Cuba, was invalided out, and returned home hailed as a warrior-patriot. From then on he was Colonel Astor. It was “Colonel Astor,” according to a headline, who “Went Down Waving Farewell to His Bride.” His death capped his rehabilitation.

Because Astor was the most socially prominent of the

Titanic

's first-class passengers, his death became a text for an outpouring of editorials, sermons, poems, and songs. Most of them suggested that wealth, whether earned or unearned, was, as always, a sign of grace, nobility of character, and elevated purpose. One song described Astor as “a millionaire, scholarly and profound” another, as “a handsome prince of wealthâ¦noble, generous, and brave.” “Now when the name of Astor is mentioned,” ran another tribute, “it will be the John Jacob Astor who went down with the

Titanic

that will first come to mind; not the Astor who made the great fortune, not the Astor who added to its greatness, but John Jacob Astor, the hero.” “Words unkind, ill-considered, were sometimes flung at you, Colonel Astor,” said the publisher and popular sage Elbert Hubbard as he hailed nothing short of an apotheosis of a dead multimillionaire. “We admit your handicap of wealthâpity you for the accident of birthâbut we congratulate you that as your mouth was stopped with the brine of the sea, you stopped the mouth of carpers and critics.” (Seven years later Hubbard himself was silenced when a German submarine torpedoed the

Lusitania

off the Irish coast.)

Some moralists of the

Titanic

disaster sounded a sour note of social Darwinism. According to them, it had been contrary to the welfare of both the nation and the human race to give over places in the lifeboats to immigrants and other dregs of humanity traveling in steerage. These places rightfully belonged to men of substance in business, culture, public service, and society. In addition to Astor, among such men who stayed behind to die a hero's death were Major Archibald Butt, President Taft's military aide; the eminent English journalist William T. Stead; copper-mining and smelting magnate Benjamin Guggenheim, who reputedly left a fortune estimated at $95 million; Isidor Straus ($50 million), owner of Macy's, the world's largest department store; and rare-book collector and Philadelphia Main Line socialite Harry Elkins Widener ($50 million). Astor's fortune was reported to be about $150 million. (A multiple of sixteen may give a very rough approximation of this amount in present-day dollars: $2.4 billion.)

A few doom-crying clergymen claimed the sinking of the

Titanic

spoke for a judgment of God on a society that had lost its way. They had in mind Astor's divorce, scandalous as well as unholy because it involved an act of adultery; his subsequent marriage, additionally unholy because he was a divorced man and his wife a teenage girl less than half his age; and his earlier years of supposedly unbridled pleasures as playboy, social butterfly, and yachtsman. “Mr. Astor and his crowd of New York and Newport associates,” thundered a prominent Episcopalian clergyman, the Reverend George Chalmers Richmond, “have for years paid not the slightest attention to the laws of church and state which have seemed to contravene their personal pleasures or sensual delights. But you can't defy God all the time. The day of reckoning comes and comes not in our own way.”

On April 19, just four days after the sinking, the Commerce Committee of the United States Senate opened its hearings on the disaster. The panel met in the ornate East Room of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on the west side of Fifth Avenue at Thirty-third and Thirty-fourth streets. (This hotel is not to be confused with its namesake opened in 1931, the Waldorf-Astoria on Park Avenue.) Since the 1890s this monumental building, as glittering an exemplar of the luxury hotel as the

Titanic

of its floating counterpart, had been one of the wonders and obligatory sights of New York City. In the lobbies and corridors of the Waldorf-Astoria the expatriate American novelist Henry James, visiting from England, claimed to have found “something new under the sun,” “a realized ideal,” “one of my few glimpses of perfect human felicity.”

Although temperamentally opposed and otherwise incompatible, it had been two Astor cousins, John Jacob IV and William Waldorf, who together had built the great hotel. For it to come into being they had enlisted a troop of lawyers and negotiators and managed to put aside their lifelong enmity in a single instance of cooperation and suspension of hostilities. As innkeepers (in a loose sense of the word), the Astors had been motivated by considerations of commerce, profit, and personal glory derived from displaying their social eminence and wealth. But they were also jointly motivated by something less measurable: the hotel imaginationâa vision of extravagance, grandeur, amplitude, order, and efficiencyâthat aimed to satisfy virtually all human needs and in doing so create new ones.

Since 1899 a British subject and head of the British branch of the House of Astor, William Waldorf oversaw his vast American real estate interests from a sumptuous London office he had built for himself at 2 Temple Place, on Victoria Embankment. As far as is known, he had no comment for the public, or for anyone else, for that matter, when the London papers carried the news of the

Titanic

sinking and his cousin's presumed death. Their fathers were brothers, and as boys the two cousins had grown up in adjacent brownstone mansions on the same Fifth Avenue block front now occupied by the Waldorf-Astoria, but they were separated by sixteen years in age and had never been friends. William Waldorfâ“Willy”âwas purposeful and disciplined; John Jacob IVâ“Jack”âwas pampered and something of a dabbler. Along with blue-blood pride and enormous wealth they inherited a long-standing personal animosity that had divided their fathers from each other and their mothers as well. Willy's mother was devoted to the quiet and upright life, the Episcopal Church, and good works; Jack's had set out to be, and became, the unrivaled party-giver and leader of New York society, possessor, as she insisted, of the exclusive title “Mrs. Astor.”

William's silence about his cousin's death was striking nevertheless, since he was the self-appointed historian, genealogist, and spokesman of an Astor dynasty by his time four generations old. Presumably he spent the day of April 15 in his baronial study at Temple Place tending to business and studying his collections of paintings, antiquities, books, and manuscripts.