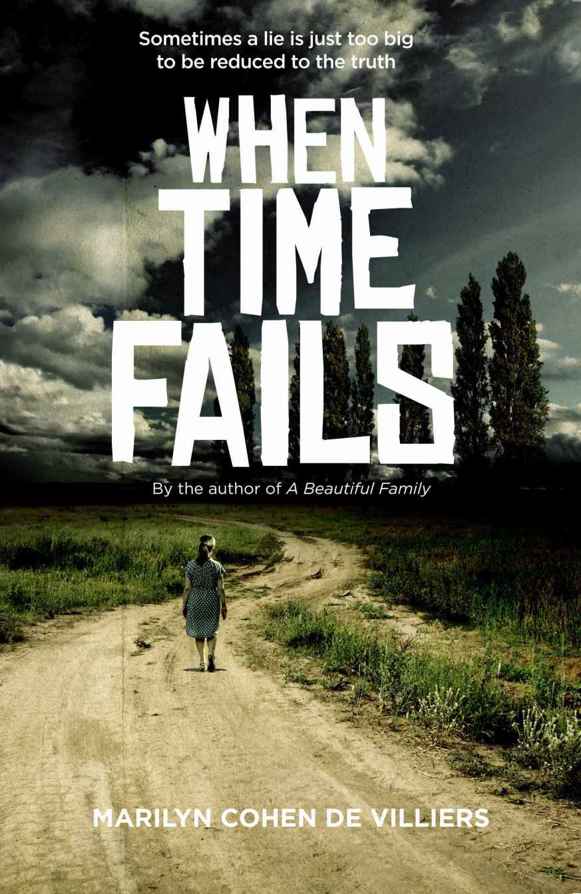

When Time Fails (Silverman Saga Book 2)

Read When Time Fails (Silverman Saga Book 2) Online

Authors: Marilyn Cohen de Villiers

When Time Fails

Marilyn Cohen de Villiers

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Glossary

Copyright © 2015 Marilyn Cohen de Villiers

First edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system without permission from the copyright holder.

When Time Fail

s

is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organisations, places, events and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance of the characters to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

ISB

N

978-0-620-65803-4

Published by Mapolaje Publishers

Edited by John Hudspith

Cover design by Francois Engelbrecht

Website: www.marilyncohendevilliers.com

For Poen

1942 – 2015

As tyme hem hurt, a tyme doth hem cure

Geoffrey Chaucer (1343 – 1400),

Troilus & Criseyde

Note to readers

When Time Fail

s

is not a story about Apartheid, the racist policy that permeated every aspect of South African life from 1948 to 1994 when national elections resulted in Nelson Mandela becoming the first democratically elected President of South Africa. However, this story plays out against the backdrop of Apartheid and its aftermath. Readers who know about Apartheid or lived through it as I did, please feel free to skip this note.

The central pillar of the Apartheid system was the racial classification of every man, woman and child as white, black, Coloured (mixed race) or Asian (Indian, Chinese etc). Humiliating tests were sometimes used to determine the race of individuals who could not readily be classified – and individuals could even be re-classified in certain circumstances: either at the whim of the authorities, or at their own request.

How you were classified determined where you lived, who you lived with, where you went to school and university, where you worked, prayed and played, which entrance you used into the post office, which bus you could ride on, where you went for medical treatment when you were ill; and finally, where you were buried. Laws like th

e

Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Ac

t

and the ironically name

d

Immorality Ac

t

criminalised love, sex and marriage between those classified as being of a different race. Th

e

Group Areas Ac

t

declared that black people would live in areas designated for black people; similarly Coloureds, whites and Asians. Th

e

Bantu Education Ac

t

decreed that black children went to black schools, Coloured children to Coloured schools, whites to white schools and so on. Th

e

Separate Amenities Ac

t

ordained that every public facility – libraries, swimming pools, beaches, hospitals, ambulances and even park benches – were designated for a specific racial group.

There were no exceptions, and no escape.

***

Because this novel is set within a specific community in South Africa, there are times when I have utilised local words and phrases. A glossary is provided at the end of this book.

2014

Annamari fingered the brown envelope, turned it over and examined the return address printed on the back. Again.It hadn’t changed. The blurred rubber stamp, faded, patchy black slightly illegible in places, nevertheless clearly stated: “Department of Land Affairs”. She turned it over and reread the front: “Mr and Mrs T van Zyl

,

Posbu

s

325, Driespruitfontein”. That hadn’t changed either.

An ominous rumble issued from the rapidly blackening clouds that rolled, threatening and pendulous, over the distant Malutis towards Steynspruit, the three naked poplars etched black against the pale sun. She shivered. She knew she should welcome the rain. It had been a long, dry winter and Steynspruit was thirsty.

But not today.

She gazed, unseeing, down the driveway to the bend which led to the turnoff from the Driespruitfontein road. Her left hand caressed the smooth, faded wood pillar supporting the corrugated iron roof of the dee

p

stoe

p

with its delicat

e

broekie lac

e

latticework put up by her Pa’

s

oup

a

to soften the austere lines of the farmhouse. It was rusting now, breaking in places. They really should fix it. But what was the point?

She rubbed her foot along the crack in the uneven stone floor – a dull red from years of liberal application of Cobra polish and worn by generations of Steyns playing, and sitting, and walking, and gossiping and just standing, as she was now, looking out across the fields. She’d forgotten to be careful when she put her coffee mug down on the peeling wooden table but she couldn’t be bothered to get th

e

lappi

e

from the nail near the door to wipe up the spill. The old wicker cane armchairs, with their threadbare floral cushions, wobbled and rocked when you sat in them. She didn’t feel like sitting. Not today.

She waited. Arno was coming home. He had something important to tell her, he’d said. Her stomach was hollow, churning. She always felt like this when her oldest son had something important to tell her – ever since that time he had called home, so excited about his new job at Silver Properties.

‘I got it, Ma,’ he’d said. ‘Alan Silverman himself interviewed me and he’s given me a job.’

Somehow, she’d managed to congratulate him, and as the years passed, the vague feeling of dread had receded. But it never really went away. Every time Arno phoned, or came home, she waited for the axe to fall.

When she heard Alan Silverman had died, she’d cried. With regret. And relief. She shouldn’t have. She should have felt bad, sad. Surely feeling relief at a man’s death, especially such a horrible death, was just another sin to add to all the sins she would one day have to account for? The envelope weighed heavily in her hand. She turned it over yet again, glanced at it and then returned her gaze to the approach road.

The first raindrops plopped heavily onto the sandy path around th

e

stoe

p

, sending up little spurts of dust. Then they fell faster and harder, and the path succumbed into a red river of mud. She peered through the torrent. The poplar sentries had disappeared. So had the bend in the road. A spear of lightning ripped the clouds apart. She jumped, startled by the thunder she’d known was coming. And laughed softly at herself. Thunder always made her jump. And sometimes reminded her of that day.

Water splashed through the leaking gutter over the front steps driving her back, away from her comforting pillar. So she sat, feet planted firmly on the red stone to still the wobbling of the wicker chair. She fingered the envelope again. And waited.

She pushed her glasses back up her nose, and squinted at her wristwatch. A silver wedding anniversary present from Thys, it had come in a fancy red box, lined in velvet. So pretty and delicate. But now, more than a decade later, she really needed a more practical timepiece.

It was getting late. Surely he wouldn’t be driving in the storm. The gravel roads, seldom graded nowadays, were treacherous in the wet. But he loved storms. While other children would cry in fear as rain pounded corrugated iron roofs, drowning out all other sound, Arno would press his little nose up against the window and watch the fury, turning around to smile at her, his blue eyes round and sparkling. Almost as if he knew, as if he shared her secret. Ridiculous. But if she knew anything about her son, he probably hadn’t stopped in Driespruitfontein, waiting out the storm as any other sensible person would, before driving on to Steynspruit.

She watched the storm intensify. It wouldn’t last much longer, but that didn’t ease her anxiety. After a good soak like this, ploughing would be able to start soon. Maybe. It all depended. She tapped the envelope on her denim-clad thigh, then got up and walked resolutely into the house. She propped the envelope on the white marble and stinkwood mantelpiece that framed the cast iron fireplace in the lounge. Thys should also be home soon. They’d open it together. Or maybe they’d wait. Whatever the Department of Land Affairs wanted this time, it could wait. She chose a log from the pile next to the fireplace and placed it in the grate. Then she chose another. And another. After the storm, a log fire would be nice and cosy, even in spring. She went back outside and watched the storm abate, moderating its fury into a fine, misty drizzle.

A car roared up the driveway. She hitched up her jeans, pleased that the diet she’d found in th

e

Huisgenoo

t

magazine actually seemed to be working this time. She smoothed her white shirt over her hips, pushed her glasses back up her nose and tucked the stray grey tendril that had escaped from her ponytail behind her ear. His fancy 4x4 was splattered in dark mud. She was glad he’d decided to come in his Land Rover rather than that absurd Porsche thing he’d driven down in last time. He’d almost wiped out the sump on a pothole.

She ignored her internal churning and smiled as he climbed out of the vehicle and waved cheerily. She waved back. Arno was home. He was safe. Everything was okay. For now.The passenger door opened slowly and a young woman with short dark hair got out. Arno put his arm around the girl’s shoulders and walked towards th

e

stoe

p

. Annamari smiled. Excited. Delighted. He had finally brought a girl home to meet her and Thys, which could only mean he was truly over Beauty. And that, at last, he was really serious about a girl. Probably even serious enough to marry her.

The girl barely reached his shoulder, she was such a tiny little thing. And such a pretty girl too, a little pale perhaps, but with a neat little figure in tight black pants, black boots and a red jacket. They smiled up at her from the foot of the steps. Annamari adjusted her glasses again. Her smile froze. A cold hand clutched her heart. She couldn’t breathe. Her lips moved as she silently begged the Lord to please, please let her be mistaken. But she knew, deep down she knew that the Lord had finally turned His back. That the time had come and He would finally wreak His wrath.