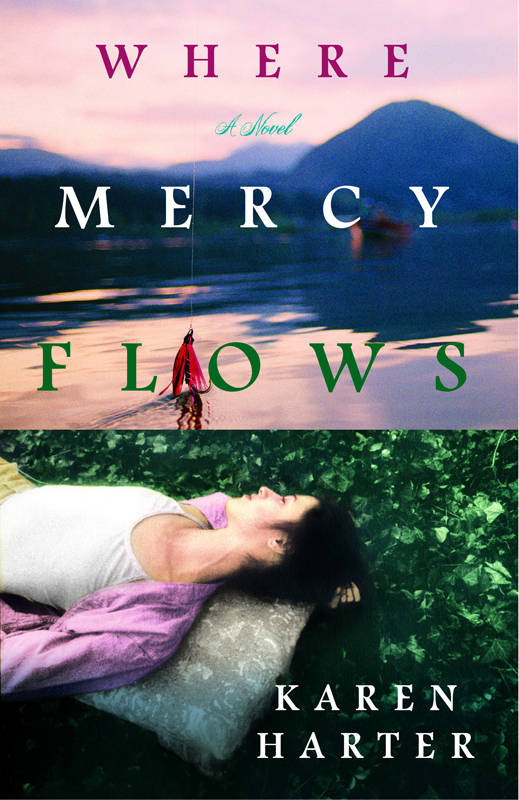

Where Mercy Flows

Authors: Karen Harter

Copyright © 2006 by Karen Harter

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Center Street

WARNER BOOKS

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

First eBook Edition: June 2009

ISBN: 978-1-599-95301-4

The trees that gathered by the river now were taller and thicker. I came around a cedar stump and saw TJ on a spit of sand

and smooth rocks and a fly fisherman just beyond him standing knee-deep in a quiet stretch of water. TJ seemed planted where

he was, watching for the first time with obvious wonder the graceful flight of a dry fly on the end of a tapered line. The

sun had dropped below the treetops, leaving that whole stretch of river in evening shadow. I hugged myself against the chill

and leaned on a ragged cedar as my eyes adjusted. The fisherman had not noticed TJ. He cast into an upstream eddy, poised

and ready as his fly drifted across its intended path. No takers. The feathered bug took off again, swooping like a tiny remote-controlled

plane above his head. My heart suddenly burst into flight like a startled bird.

It was that perfect stance, arm moving just so. That slight tip of his head. Despite the unfamiliar cap, I knew. TJ stepped

closer. Upon hearing the crunch of the boy’s shoes in the river rocks, the Judge turned to face him. I gasped and ducked behind

the stump.

To Jeff, the father of my children,

to Daddy,

and to my Father in Heaven.

I am truly blessed.

Contents

Many thanks to my hard-nosed writer friends who provided the perfect blend of critique and encouragement: Erika, Gloria, Juanita,

Lani, Mary, Margo, Nancy, Peggy and Mary. I love you all.

Renee Riva Capps, you have a knack for popping in by e-mail just when I need a good belly laugh. Carrie and Grace, I loved

the late-night dream sessions, and yes, I will wear tangerine.

Ryan and Michael, thanks for allowing me to be a mom who sometimes forgot to do motherly things like cooking and baking. I’m

getting better at it now, so please come home. I’m grateful for my family (oh, how blessed I am to have each one of you!),

whose love and belief in me means more than you may ever know. Daddy, you were a tough editor and coach; Mom, my loyal fan

no matter what I wrote about you; and Maria, a great cheerleader. Jeff, I know it took a lot of faith to let me do this thing.

Thanks for believing.

To my incredible agent, Deidre Knight, as well as my editor, Christina Boys, and the team at Time Warner Book Group, thanks

for helping to make my dream come true.

T

HE JUDGE ALWAYS had the final say. Right or wrong, he was God. His truth was a hard, unbending line that never wavered. Not

even for me.

When I was young I called him Daddy.

Of course, I also lay in the cool grass of summer and imagined that clouds were dinosaurs and that just as the sky had no

beginning or no end, life held limitless possibilities for me.

My world was twelve acres framed by a wadable creek in a gully to the east, the Stillaguamish River to the south, a stand

of poplars lining our long driveway on the west and Hartles Road to the north. Our river came like a train from far away.

It slowed as it rounded the bend to pass our house on its way to somewhere—the ocean, I guessed, and I believed as children

do that my life, like the river, was destined to flow as easily around each bend.

I knew little of death, except that Great-grandpa Dodd had died while plowing the back quarter of his sixty acres. The job

accomplished, he promptly had a heart attack and drove the old John Deere straight down the hill into the churning river.

No one seemed to mind much, because he was very old and they thought it fitting that he and his rusty tractor had gone down

together. It was symbolic, they said. His job on earth was done, and then he was swallowed up by the very river that had sustained

him.

There were no lamenting dirges at the graveside and only a few quiet tears. Great-grandpa was laid out in his Sunday-go-to-meetin’

suit, looking to me like he was taking his after-supper nap on the sofa, but for once he didn’t snore. Most of the friends

and relatives gathered in the dewy grass were in full Salvation Army uniform—dark military suits with rank designations on

their shoulders, the ladies in bonnets with bows on the sides as big as cauliflowers. They sang hymns and played their cornets

and trombones. My father didn’t sing much. He stood silently, gripping my hand firmly so I couldn’t take off my shoes and

socks or stare down into the hole where they put Great-grandpa. My sister held a tissue in her white gloves and sang all the

songs by heart. Auntie Pearl smiled at me afterward and said Grandpa had gone home to be with Jesus.

That seemed right to me. The way it was supposed to be. My life and the lives of the ones I loved would follow a similar course,

meandering yet purposeful, and ending only upon reaching our destination. Old age.

My father, the only son of the fourth generation of American Dodds, had been expected to churn and plant the rich valley soil

as his fathers had before him. Instead, he enrolled in the University of Washington to study law. His father, Lee Dodd (I

called him Grandpa Lee), raised his children within twenty square miles of farms and woodlands in northwest Washington, venturing

as far away as Seattle only for the rare funeral or special Salvation Army meeting. I suppose the way my father turned out

was largely due to this narrow and rigid upbringing.

The sound of windshield wipers squeaking across dry glass broke my muse. I switched them off, wondering when the rain had

stopped and how I had driven so far with no memory of the passing scenes. The last thing I remembered was the ghostly shape

of the Space Needle standing in the fog and then crossing an overpass to see the sprawling University of Washington campus

off to my right. Now, as I continued north, an expanse of bright sky burned a path from the Olympic mountain range on the

west to the Cascade Range on the east.

I was going home. After seven hard years, home to my river valley, Mom—and the Judge. The thought alternately warmed and then

chilled me to the bone.

“TJ?” I ran the fingers of my free hand through my son’s dark hair as I steered onto the freeway off-ramp. His eyes opened

and he immediately raised himself to peer out the window.

“Are we there?”

“Not yet. We’re getting close. I want you to see this.”

“What?”

“The scenery. Look how green it is.”

He glanced at a field of black-and-white cows and craned his neck in all directions before reaching for the rumpled map on

the dashboard. His pudgy fingers traced the lines leading to the X that represented his grandma and grandpa’s house as they

had done at least a dozen times in the past two days. “You gotta go right there, Mom. Down this road, then turn on this road

. . .”

“Turn it around. It’s upside down.”

He righted it with clenched brows and then studied it some more. “Don’t turn on this line, Mom. This is a river.”

“That’s the river that runs behind their backyard. And don’t you ever go down there alone. You hear me?”

He nodded. I made a mental note to mention it again.

“Does my grandma make cookies?”

“Probably.”

For the next twenty miles TJ asked questions and played with the spring air rushing by his open window while I became increasingly

apprehensive of what was to come. The heaviness in my chest was noticeable again. I took several deep breaths and tried not

to think about it.

I slowed the Jeep as we bumped over a railroad track and pulled into the parking lot of a small store with gas pumps out front.

The Carter Store. The sign had big letters that lit up now and a newer roof that extended over a large porch that hadn’t been

there before.

“You want a pop or something?”

TJ’s head bobbed enthusiastically, which it would not have done if he knew how close we were to our destination. I parked

next to a shiny black pickup, pressing my hand to my chest. TJ jumped out and rushed toward the wooden porch and then turned

back impatiently.

“Come on, Mom!” His brows rose imploringly above his dark eyes, and I marveled for the thousandth time at how beautiful he

was and that he could possibly be mine.

“Give me a minute,” I called out my window. I took another deep breath. “For Pete’s sake, we just got here.” I climbed out

and stretched my stiff legs, smoothing the damp wrinkles behind the knees of my jeans before following him into the store.

When I was a young girl, the Carter Store was owned by a spunky old woman named Nellie. I wondered if the new proprietor was

related. The store had been smaller then. Just the essentials crowded the board shelves, in no logical order. Dish soap and

tinfoil were lined up next to motor oil. There were ropes and wire racks for making toast over a campfire, stale marshmallows,

and hot dog buns. Best of all, and worth every mile of the bike ride in the sweltering sun, was the array of candy in a glass

case by the cash register. If she wasn’t too busy, Nellie let my sister, Lindsey, and me arrange our penny candies and licorice

whips on the counter, offering free advice on how to get the most bang for our quarter. One lucky day we happened to arrive

just after the store’s old freezer had wheezed its last. We rode away with all the Popsicles we could carry, licking frantically

as the juice ran down our arms.

TJ knew his way around convenience stores, even this little Ma and Pa shack way out in the country in another state. He headed

straight for the glass doors of the cooler at the back and pulled out an orange soda. “You wanna soda, Mom?”

Actually, I craved something stronger. “I’ll have whatever you’re having.” He passed me a bottle and followed me to the cash

register, where a tall young man stooped with his elbows on the counter, talking to the middle-aged cashier.

“Oh, sorry.” He waved me up to the counter. “I’m not buying anything. Just yackin’.” He stepped aside, pulling a fly-fishing

magazine from the worn wooden counter. I nodded a half smile and felt him watching as I paid the heavy-jowled man behind the

cash register.

“Did that fish come out my grandpa’s river?” I turned to see TJ pointing up at the cover of the guy’s magazine.

“I don’t know. Which river is your grandpa’s?”

TJ looked to me for help. “The Stilly,” I said, which was the local abbreviation for the Stillaguamish River.

“Oh, no. This fish isn’t from around here.” He pointed to the red print beneath the photo of a glistening brown trout. “Says

here this guy came out of the Yellowstone in Montana.” He passed the magazine to TJ for closer inspection. “You ever caught

a fish like that?”

TJ shook his head. “I never caught a fish yet. But I’m going fishing with my grandpa. He doesn’t know I’m coming. We drove

a long time, ’cause we’re going to surprise him.”

The guy tossed me an amused glance and then resumed a serious expression. “And what is your grandpa’s name?”

He giggled. “I just told you. Grandpa.”

“Judge Dodd,” I volunteered.

The guy shook his head. The name meant nothing to him. I surmised he was new to the area or just passing through.

“The worm man.” This came from the store proprietor as he passed me my change. I squinted through strands of wavy auburn hair

that had fallen across one eye. The old man was obviously confused.

“My father is Judge Blake Dodd. He lives about three miles downstream.” I passed TJ his soda and turned toward the door.

“Did you say Blake?” The tall guy slapped his thigh and rolled his eyes toward the man behind the counter with a

how-could-I-be-so-stupid?

look. “I know Blake. Met him fishing under the bridge one day. There was a mayfly hatch on and I had nothing but wet flies.

He gave me one of his. Tied it himself. I didn’t know he was a judge, though.”