Which Way to the Wild West? (15 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

A

mericans could now cross the nation in eight to ten daysâa fact that seemed absolutely amazing in 1869. “Every man who could command the time and money was eager to make the trip,” wrote one reporter.

mericans could now cross the nation in eight to ten daysâa fact that seemed absolutely amazing in 1869. “Every man who could command the time and money was eager to make the trip,” wrote one reporter.

Early journeys often didn't go smoothly. First of all, both the Union Pacific and Central Pacific were still busy working on the

tracks, rebuilding all the sections of rail they had built too quickly the first time. Also, no one had really figured out how things like meals should work. The train didn't serve food. Instead, it stopped at stations along the track and hungry passengers tumbled out and rushed into nearby dining halls. Knowing the train would leave again in half an hour, everyone shouted at once:

tracks, rebuilding all the sections of rail they had built too quickly the first time. Also, no one had really figured out how things like meals should work. The train didn't serve food. Instead, it stopped at stations along the track and hungry passengers tumbled out and rushed into nearby dining halls. Knowing the train would leave again in half an hour, everyone shouted at once:

“Steak!”

“Coffee!”

“Bread!”

“Trout!”

“Waiter, a napkin!”

In addition to the stress of getting back to the train on time, a traveler named Susan Coolidge noticed that every place she went served the exact same thing. “It was necessary to look at one's watch to tell whether it was breakfast, dinner, or supper we were eating.” she said.

As the train headed farther west, riders ran into a kind of culture clash. Wealthy riders from eastern cities suddenly found themselves sharing train cars with pistol-packing miners who spat tobacco juice on the floor. The miners turned out to be friendly, though, often holding out bottles of whiskey to the fancy folks and saying, “Smile?” (western slang for “Have a drink?”).

Slightly less friendly were the men who pulled off the West's first major train robbery. It all began on the morning of November 4, 1870, when A. J. Davis got a telegram from a friend in Oakland, California:

“Send me sixty dollars and charge to my account.

âJ. Enrique”

This was the coded message Davis was waiting for. It meant that a Central Pacific train had just left Oakland, heading west with $60,000.

At midnight, when the train slowed down to pass through the town of Verdi, Nevada, Davis and four other men in black masks jumped on board. They unhooked the engine car and express car (which had the money boxes) from the rest of the train. These first two cars continued on, while the other cars, full of snoring passengers, drifted quietly back along the tracks.

Davis and the gang busted into the engine car and pulled their guns on the engineer, Henry Small. They told him to drive on a bit, then made him stop at a dark spot. They ordered him to knock on the door of the express car.

“Who's there?” the guard asked.

With a gun sticking in his back, the engineer was forced to say, “Small.”

Recognizing the voice, the guard opened the door. The robbers charged in, cracked the money boxes with crowbars, filled their bags with twenty-dollar gold coins, hopped onto horses they'd hidden along the tracks, and rode off in separate directions.

Henry Small, meanwhile, drove his engine car back to the rest of train and reattached the other cars. The passengers were still asleep. They had no idea anything had happened.

So the first train robbery was a successâthough a short-lived one. Over the following weeks the robbers were all tracked down and arrested. The stolen gold was recovered, except for about 150 coins, which the thieves must have buried somewhere along the Truckee River. (People in Nevada are still searching for that stashâit's worth over a half a million dollars today.)

A

nother early traveler on the transcontinental railroad was Red Cloud, the Lakota chief who had recently won his war against American forces.

nother early traveler on the transcontinental railroad was Red Cloud, the Lakota chief who had recently won his war against American forces.

In 1870 U.S. government officials invited Red Cloud to come to Washington, D.C. They wanted to talk to him about how to preserve the fragile peace between settlers and Indians in the West. Red Cloud and fifteen other Lakota leaders boarded a Union Pacific train and headed east through Omaha, Chicago, and on to Washington. There they were met by the government's commissioner of Indian affairs, a Seneca Indian named Ely Parker.

“I am very glad to see you here today,” Parker said. “I want to hear what Red Cloud has to say for himself and his people.”

But Red Cloud was tired from the long trip. “Telegraph to my people and say that I am safe,” he told Parker. “That is all I have to say today.”

Red Cloud and the other Indians were taken to an expensive hotel, where their huge suites were furnished with pitchers of lemonade and baskets of oranges, nuts, and cigars. The next day they were given fancy American suits (which they found terribly tight and uncomfortable) and went to the Capitol building to watch senators make speeches (which they found terribly boring). A photographer asked permission to take Red Cloud's picture, but he refused, saying, “I am not dressed for such an occasion.”

He didn't want anyone photographing him in the ridiculous suit. Then they went on to the White House to have dinner with President Ulysses S. Grant. The Lakota chief Spotted Tail particularly loved the strawberry ice cream. “Surely the white men have many more good things to eat than they send to the Indians,” he commented.

When everyone finally got down to business, Ely Parker

explained that the United States was committed to living peacefully with the Plains Indians. Red Cloud agreed with this goal and thought it should be easy to achieve. “The white children have surrounded me and left me nothing but an island,” Red Cloud said. Let the Lakota keep this island of land, he explained, and there will be no more war.

explained that the United States was committed to living peacefully with the Plains Indians. Red Cloud agreed with this goal and thought it should be easy to achieve. “The white children have surrounded me and left me nothing but an island,” Red Cloud said. Let the Lakota keep this island of land, he explained, and there will be no more war.

Next Red Cloud stopped off in New York City, where crowds of people lined the streets and cheered as he rode past on a horse. “We want to keep the peace,” Red Cloud told New Yorkers. “Will you help us?”

Red Cloud understoodânow more clearly than everâthat he would need help. The trip gave him a close-up view of busy American factories and enormous American cities. There was simply no way he and his warriors could continue winning wars against such a massive and growing nation.

So Red Cloud headed home a bit depressed. And it could not have helped his mood to see so many trains packed with people racing west. He must have been wondering:

Where are all these people going? How long until they start crowding onto our land?

Where are all these people going? How long until they start crowding onto our land?

O

ne of those heading west was Nat Love, a teenager who had grown up in slavery in Tennessee. “I was at that time about fifteen years old,” he said of the moment he left home.

ne of those heading west was Nat Love, a teenager who had grown up in slavery in Tennessee. “I was at that time about fifteen years old,” he said of the moment he left home.

“And though while young in years, the hard work and farm life had made me strong and hearty, much beyond my years, and I had full confidence in myself as being able to take care of

myself and making my way.”

myself and making my way.”

Nat Love

Love traveled west to Dodge City, Kansas, a booming town along the railroad. What was there to see in town? “A great many saloons, dance halls, and gambling houses,” Love said, “and very little of anything else.”

But Love did see one thing that interested him: cowboys. Even more interesting was that many of them were African American. Love decided to find out exactly what these guys did for a living. The cowboys told him that they had spent the last few months leading a huge herd of cattle from Texas all the way here to Dodge City. They were about to head home to Texas to do it all over again. Love decided he'd like to join them, and went to find the boss of the crew.

“Can you ride a wild horse?” the boss asked.

“Yes, sir,” Love responded.

“If you can I will give you a job.”

The boss pointed out a horse named Good Eye, the wildest horse he had. He told Love to jump on. As Love approached the horse, a cowboy named Bronco Jim warned him that the horse would probably send him flying.

“I told Jim I was a good rider and not afraid,” Love said.

The cowboys crowded around, eager to watch Good Eye toss this skinny kid into the air.

Fifteen-year-old Nat Love swung up onto Good Eye, and his cowboy tryout began with a jolt. “This proved the worst horse to ride I had ever mounted in my life,” he said. The huge beast twisted and kicked, but Love somehow stayed in the saddle. When Good Eye finally tired, Love jumped offâand saw surprise in the eyes of the watching cowboys. “They had taken me for a tenderfoot, pure and simple,” Love said.

From then on, Nat Love was a cowboy.

N

at Love came to Kansas in 1869. It was a good time to get into the cowboy business.

at Love came to Kansas in 1869. It was a good time to get into the cowboy business.

The long and bloody Civil War had ended just four years before. When soldiers from Texas came home, they found huge herds of cattle wandering around the state. No one had been paying much attention to them during the war. Now there were millions of them.

Texans like steak, but they couldn't eat five million cows. And when you have a lot more of something than people want to buy, the price goes way down. In fact, cattle were worth only about three or four dollars each in Texas.

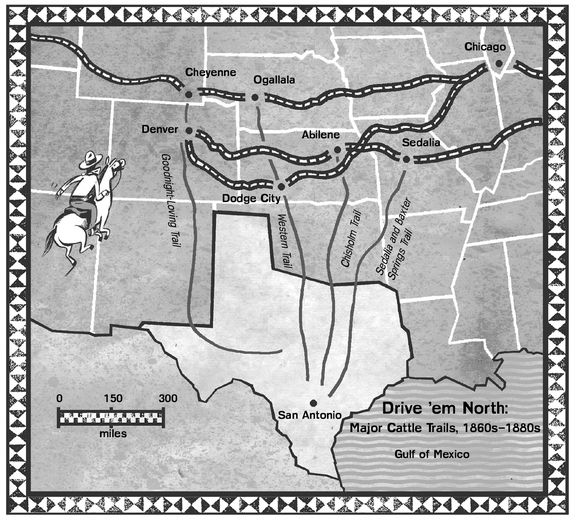

But remember, at this exact time, new railroads were being built across the country. This gave Texans an idea: Suppose we can get our cattle north to those railroads? Then trains can carry them east to busy cities, where cows are worth forty dollars each!

There was clearly money to be made. The challenge was getting the animals north to the railroad. That was the job of the cowboys.

“I

was the poorest, sickliest little kid you ever saw,” said a cowboy named Teddy Abbott. “All eyes, no flesh on me whatever.”

was the poorest, sickliest little kid you ever saw,” said a cowboy named Teddy Abbott. “All eyes, no flesh on me whatever.”

When Abbott was ten years old, his father decided to let him help drive a herd of cattle north from Texas. “The idea was it would be good for my health,” Abbott remembered. And it was. He spent the next few years outdoors, riding horses and roping cattle. “Those

years were what made a cowboy of me,” said Abbott. “Nothing could have changed me after that.” When he turned eighteen, Abbott left home to become a full-time cowboy.

years were what made a cowboy of me,” said Abbott. “Nothing could have changed me after that.” When he turned eighteen, Abbott left home to become a full-time cowboy.

Like Abbott, most cowboys were young men from the South. They were a diverse bunch, including many African Americans, Mexicans, and Native Americans. Skill was more important than

skin colorâand so was size. “The cowboys were mostly mediumsized men,” Abbott explained. “A heavy man was hard on horses.”

skin colorâand so was size. “The cowboys were mostly mediumsized men,” Abbott explained. “A heavy man was hard on horses.”

For a long cattle drive, ranchers would hire about six cowboys for every one thousand head of cattle. Spending seventeen-hour days on their horses, the cowboys surrounded the cattle and kept them moving north. They did this every day, seven days a week, for three or four months.

“We had no tents or shelter of any sort other than our blankets,” one cowboy said about life on the trail. “Should anyone become injured, wounded, or sick, he would be strictly âout of luck.' A quick recovery and a sudden death were the only desirable alternatives in such cases, for much of the time the outfit would be far from the settlements and from medical or surgical aid.”

And there were plenty of ways to get hurt: poisonous snakes, rushing rivers that drowned cows and men, sudden storms of hail or lightning (Teddy Abbot was actually hit by lightning twice). But the thing cowboys feared most of all was a stampede, when herds of cattle suddenly panicked and started running wildly. These were naturally nervous animals. Almost any sudden sound could set off a stampede. A thunderclap, a gunshot, a coyote's yelpâeven the clank of the cook's iron pots banging togetherâcould send the cattle running. This made nights the most dangerous time for cowboys.

“I

magine, my dear reader, riding your horse at the top of his speed through torrents of rain and hail, and darkness so black that we could not see our horses' heads, chasing an immense herd of maddened cattle, which we could hear but could not see, except during the vivid flashes of lightning, which furnished our only light.”

magine, my dear reader, riding your horse at the top of his speed through torrents of rain and hail, and darkness so black that we could not see our horses' heads, chasing an immense herd of maddened cattle, which we could hear but could not see, except during the vivid flashes of lightning, which furnished our only light.”

That was Nat Love's frightening description of a night stampede. Even when it was too dark to see, Love and the boys had to jump onto their horses and chase down the speeding eight-hundred-pound animals. The stomping cattle could easily trample each otherâand cowboys too. After one night's stampede, Teddy Abbott had the job of searching for a missing cowboy. “We found him among the prairie dog holes, beside his horse,” Abbott said. “The horse's ribs were scraped bare of hide, and all the rest of horse and man was mashed into the ground as flat as a pancake.”

Cowboys discovered that the best way to keep cattle calm at night was to sing to them. “The singing was supposed to soothe them, and it did,” Abbott remembered. Two cowboys would ride along either side of the herd, taking turns singing back and forth. They soon got so sick of the songs they knew that they started making up new ones. Here's a sample from “The Old Chisholm Trail”:

I'm up in the mornin' afore daylight

And afore I sleep the moon shines bright

Oh, it's bacon and beans most every dayâ

I'd as soon be a-eatin' prairie hay â¦

And afore I sleep the moon shines bright

Oh, it's bacon and beans most every dayâ

I'd as soon be a-eatin' prairie hay â¦

So after spending all day in the saddle, cowboys had to take a twohour shift of singing every night. On a good night, they might get

four hours of sleep. “When you add it all up, I believe the worst hardship we had on the trail was loss of sleep,” said Teddy Abbott. “Sometimes we would rub tobacco juice in our eyes to keep awake. It was rubbing them with fire.”

four hours of sleep. “When you add it all up, I believe the worst hardship we had on the trail was loss of sleep,” said Teddy Abbott. “Sometimes we would rub tobacco juice in our eyes to keep awake. It was rubbing them with fire.”

If cowboys and their herds survived all of thisâand they usually didâthey made it north to the railroad lines by the end of summer. The plains were covered with thick grass, so there was plenty for the cattle to eat until the cowboys could sell them.

But the cowboys weren't the only ones who wanted to use this land.

I

n 1870 a ten-year-old boy named Percy Ebbutt, along with his father, older brother, and three family friends, sailed from Britain to the United States. They shared a dream: to start their own farm on the American Great Plains. The group traveled west by train, then bounced across the plains in a wagon to their new land in Kansas. “Of course, boy-like, I was looking forward to our life on the prairie as being all play or adventure,” Ebbutt remembered.

n 1870 a ten-year-old boy named Percy Ebbutt, along with his father, older brother, and three family friends, sailed from Britain to the United States. They shared a dream: to start their own farm on the American Great Plains. The group traveled west by train, then bounced across the plains in a wagon to their new land in Kansas. “Of course, boy-like, I was looking forward to our life on the prairie as being all play or adventure,” Ebbutt remembered.

There was plenty of adventure, but not so much play. After

unloading all their clothes and supplies, they broke up the wooden crates and built a tiny, shaky shack. Then one of the men tried to cook supper.

unloading all their clothes and supplies, they broke up the wooden crates and built a tiny, shaky shack. Then one of the men tried to cook supper.

“Harry Parker made his first attempt at bread-baking, but was not over successful. The bread was baked in a great iron pan, and was as hard as a well-done brick, and about as digestible.”

Percy Ebbutt

Men chopped off chunks with an ax. Then they turned to a much more troubling topic. “None of us knew anything whatever of farming,” Ebbutt said. What made this family decide to cross an ocean to take on the enormous challenge of starting a farm? That's easy: there was lots of land available on the Great Plains, and it was cheap.

Up until recently, no one had thought of the dry, treeless plains as good farmland. Maps of the time actually labeled this vast region

“the Great American Desert.” That had started changing after the government passed the Homestead Act in 1862. This law said that any U.S. citizen twenty-one or older, or any immigrant who was in the process of becoming a citizen, could claim 160 acres of land on the Plains. You had to pay a ten-dollar filing fee, and you had to live and work on your property for five years. Then the land was yours.

“the Great American Desert.” That had started changing after the government passed the Homestead Act in 1862. This law said that any U.S. citizen twenty-one or older, or any immigrant who was in the process of becoming a citizen, could claim 160 acres of land on the Plains. You had to pay a ten-dollar filing fee, and you had to live and work on your property for five years. Then the land was yours.

The Homestead Act made it easy to get land. Maybe too easy. Families raced west to claim their landâbut it takes a lot more than land to make a successful farm. You need money to buy seeds, farm equipment, animals, and food for your family while you're waiting for your first harvest. And of course, it helps to know how to actually run a farm.

Many homesteaders (or pioneers, as they came to be known) figured this out the hard way. Percy Ebbutt later warned potential homesteaders: “If you have made up your mind to go, you must also make up your mind to rough it.” But stories about “roughing it” didn't scare people away from claiming homesteads on the Great Plains. For thousands of families, this was their one chance to get land of their own.

It was only after arriving on the Plains that they realized what “roughing it” really meant.

M

artha Wooden took a train west to join her husband and sons, who had already claimed a piece of Kansas land. Martha's husband met her at the train station and they rode in a wagon toward their claim, which was about forty miles away. She gazed out at the flat grassy land stretching to the horizon in every direction. She didn't

see a single tree or house all day. Then it started to get dark. She noticed her husband looking a little concerned. He stopped the wagon.

artha Wooden took a train west to join her husband and sons, who had already claimed a piece of Kansas land. Martha's husband met her at the train station and they rode in a wagon toward their claim, which was about forty miles away. She gazed out at the flat grassy land stretching to the horizon in every direction. She didn't

see a single tree or house all day. Then it started to get dark. She noticed her husband looking a little concerned. He stopped the wagon.

“Well, I guess I'm lost,” he announced.

“Lost!” she said. “Out here on this lonely prairie?” Then she heard a loud howl.

“And what is that?” she asked.

“Oh, I guess you hear the coyotes.”

Martha's husband got out of the wagon with a lantern, and she drove slowly behind him as they searched for their land. That was Martha Wooden's introduction to pioneer life.

There was a good reason Wooden didn't see any houses that first day: many newcomers didn't have the time or materials to build them. When a young pioneer named Howard Ruede arrived in Kansas, for example, he did what many others didâhe got out his shovel and started digging. In a land with no trees, the quickest way to build a shelter was to dig one in the ground. “I tell you it is no easy work,” Ruede reported to his family in Pennsylvania.

Ruede's six-foot-deep “dugout” was a good temporary solution, though it had its drawbacks. “It's awful hot,” he wrote from the floor of his new home.

“The sweat runs off of me, and some of the drops wet the paper; so if you can't read it, you'll know the reason.”

Howard Ruede

A teenage girl described another problem with having dirt walls and a grass roof. “Sometimes the bull snakes would get in the roof, and now and then one would lose his hold and fall down on the bed,” she said. Then someone would have to grab a hoe, fight the snake, and toss it outside.

While sitting around drinking coffee one morning, another group of pioneers had a different sort of animal encounter. After pouring himself another cup, one of the men noticed something strange in the bottom of the pot. He turned to his friend Jim.

“Where'd you get that egg in the bottom of the coffeepot, Jim?”

“There's no egg,” Jim said.

“But I can see an egg.”

Jim took the coffeepot, turned it upside down, and out plopped a dead frog, swollen to several times its normal size. The men shrugged, then did what they did every morning: they started a long, hard day of work.

Other books

El libro de Los muertos by Patricia Cornwell

Highlander's Rebellious Love by Donna Fletcher

Hard As Steele (A BBW Paranormal Romance) (Timber Valley Pack) by Georgette St. Clair

The Darkest Corners (The Club Book 4) by Rhodes, Katherine

The Serpent's Shadow (The Kane Chronicles, Book Three) by Riordan, Rick

Weavers by Aric Davis

Wicked Weekend by Gillian Archer

At Death's Window by Jim Kelly

The Egg and I: How to Make Incredible Omelets and Frittatas by Weaver, Dennis