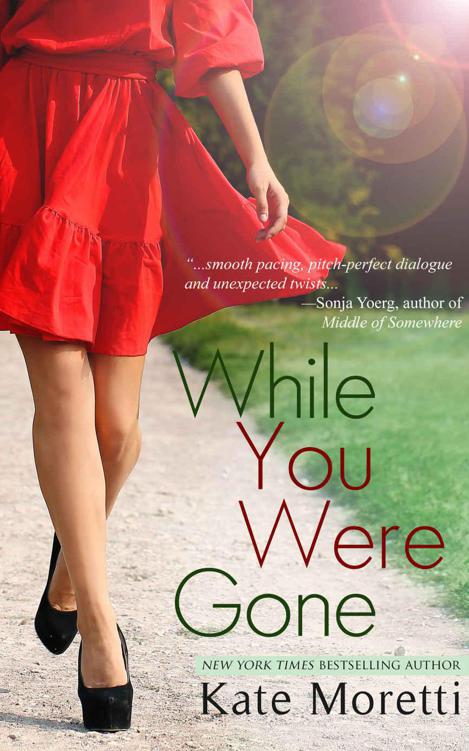

While You Were Gone: A Thought I Knew You Novella

Read While You Were Gone: A Thought I Knew You Novella Online

Authors: Kate Moretti

Table of Contents

While You Were Gone

Copyright © 2014 by Kate Moretti. All rights reserved.

First Edition: July 2015

Thank you for downloading this Red Adept Publishing eBook |

Join our mailing list and get our monthly newsletter filled with upcoming releases, sales, contests, and other information from Red Adept Publishing. |

|

|

Or visit us online to sign up at |

|

Red Adept Publishing, LLC

104 Bugenfield Court

Garner, NC 27529

http://RedAdeptPublishing.com/

Cover and Formatting:

Streetlight Graphics

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to locales, events, business establishments, or actual persons—living or dead—is entirely coincidental.

For Lily and Abby, chase a passion. Anything you want. It’s important.

Dear Reader

While You Were Gone

is a stand-alone novella based on the novel

Thought I Knew You.

It is, simply put, another side to the story. It’s not the same story, but if you read this novella

,

you will know the end of

Thought I Knew You.

You’ll know what happened to Greg (I think that’s okay, but you should know this going in).

When I published

Thought I Knew You,

I expected a certain level of conflict over Greg, Claire Barnes’s husband. Some readers told me they didn’t know why Claire would ever keep him in her life (in any regard). This didn’t make sense to me.

But Greg is not a bad person

, I said.

He did a bad thing.

To me, these are obviously divergent character traits.

But he’s a good father, sometimes a good husband,

I’d insist. It wasn’t always good enough.

No story is one sided. No person is all good or all bad. Those split-second decisions, driven by loss, insecurity, grief, or anger, these are the decisions that interest me: the ones that don’t live in the black and white. The mistakes. The human-ness.

While You Were Gone

is my attempt to make Greg and Karen human. Lovable, even. Despite their mistakes.

Thanks for reading.

Kate

July 02, 2015

Chapter 1

N

o one likes the call that comes in the middle of the night, the one that jolts you from the deepest sleep and sets your heart racing. If you’re getting that call, someone is either in jail or in the hospital. Maybe someone you vaguely remember loving has been kicked out of Tig’s bar. Again. Their keys have been taken away, and they are sitting on the front stoop, under a drooping awning and a blinking Miller Lite sign, with a fat lower lip caused by either fist or fall. And if you’re me, that someone is your mother, which is ridiculous and embarrassing. Then again, Paula’s never been one for subtlety.

I don’t want to go. I’ve gone the last three times, and it’s Pete’s turn. I listen to some idiotic Nickelback ring-back tone, as though my brother isn’t thirty years old with a wife and three kids under five and is instead a sullen high school sophomore with pocked cheeks and an addiction to angsty pop music. Maybe I’m a tiny bit bitter to be the one getting this call. Why doesn’t Tig ever call Pete? Oh right, because he never answers.

His voicemail clicks on, and I leave a hasty message. “Hi. Needed you. Paula is at the bar again. Thought maybe you could go this time? I have an early-morning violin audition. Hello? No. Got it. Typical.” I slam the phone on the nightstand and shove my feet into brown moccasins that Paula got me for Christmas last year—maybe two years ago. Last year, Paula bought us scotch.

I throw on a sweatshirt and snatch my keys off the hook. I consider bringing her here, letting Paula sleep it off on the couch. I picture the condition of Paula’s house: frozen pizza boxes and empty liquor bottles balancing on top of the garbage bin. Last time I was there, I pointed out a collection of mouse droppings in the pantry, and she waved me away with an irritated sigh. I’d bet money they’re still there.

Cold air whips around my face and my neck. It smells like bonfires and marshmallows, the way November air should. Clean and fresh. I climb into my faded blue Toyota and turn the key. The engine brays and gasps, and for a moment, I think I’m going to have to call Pete back or maybe even the police. Eventually, it turns over with a grumble that shakes the whole car.

I cut a U-turn right and check the clock: 3:15 a.m. I know that whatever time I pull into that dusty parking lot spotted with gleaming Harleys, there will be a fight. The bars close at four, and even a moment before is too soon. I’m mostly past the point of humiliation, but every once in a while, it sneaks up on me, and my stomach coils while I think,

this is my mother. This is not the way this should be going down.

I expect her to be sitting on the front stoop, but she’s not. The parking lot is surprisingly empty, and the music from inside isn’t the typical country twang but an electric rock, loud and garbled, sung live with shitty equipment.

Paula sits hunched over a tumbler of something clear, smoking a cigarette in the far corner of the bar. She’s talking to the guy next to her, who looks my way when I walk in. She glances up, sees me, and rolls her eyes. She shouts across the bar at Tig.

“You know, Tig, one of these days, I’m gonna stop coming here. Every time I let a little loose, you up and call my babysitter.” Her voice is rough cut, and she coughs. I stop two feet from her and give her time to get herself up. She looks me up and down, a small sideways smirk on her face. “You mad, baby girl?”

“Well, it’s three a.m. I have a nine o’clock audition tomorrow. I’ve been… happier.”

She stands up slowly, trying not to stumble, with slow, deliberate, underwater movements. She actually looks good, my mother—tall and skinny like me, and her highlighted dark bob angled against her face is slick and trendy. She doesn’t look like a woman falling apart. She’s aged well. We could almost pass for sisters, a fact that delights her to an embarrassing degree. She brings it up to strangers, to people at the movies behind the popcorn counter.

Some people think we look like sisters. I’m her mother, you know. Crazy, right?

She picks her way to me. It’s only a few steps, but she stumbles, her right ankle turning. Instinctively, I stick my arm out to catch her. She’s as light as a child. She leans against me, sneezes, and I realize her cough wasn’t nicotine fueled.

“God, Paula. Are you still sick? Have you been to the doctor?” I’d talked to her last week, and she’d coughed a blue streak into my ear. I’d asked her to see someone, but she brushed me away,

too busy.

Doing what? I can’t even fathom it.

She giggles and taps her finger to the bridge of my nose. “Look at you. It’s like you’re my mama, not the other way around.” She perks up and holds her index finger an inch from my face. Her eyes go bright, and she wriggles away from me. “I’ll be right back.”

I watch her sashay across the room, her narrow hips swinging, and I follow her, a dutiful puppy. She leans in to a tall, good-looking man closer to my age than hers, planting a wet, lingering kiss near his ear. “You come back again, soon, okay?”

He laughs and hugs her back. I look over at Tig, who is drying a glass behind the counter, and he shakes his head at me. Humiliation hits, which, in turn, sparks a surge of anger. My mother coils herself around this cute stud of a man, who either doesn’t realize that she’s closer to sixty than forty or doesn’t care. I march up and grab her elbow, hard. Her face whips around to mine, her eyes narrow, and her mouth bunches like I’m a kid playing under a clothes rack while she’s trying to shop.

How dare I?

“We’re leaving,” I announce, and I see Tig out of the corner of my eye, paused in his toweling and watching us carefully. My mother can be explosive, all sticky-sweet pecan pie, with that sugary, almost Carolina accent one minute. Then boom. Her anger knows no limits. I remember the long fingernail scratches weeping fat drops of blood down my father’s arm. He wrapped a towel around his arm and cursed at her,

Goddammit, Paula.

She ran around, clucking and preening, administering antibacterial cream and bandaging—apologetic to the point of being almost gleeful. No one but me was surprised when he left.

I yank her arm harder. “Now.” She follows me out, waggling a finger wave to the remaining patrons.

I jerk open the passenger-side door and push her in.

“Ouch, Karen. That seems unnecessary.” She pouts, dramatically rubbing the spot above her elbow.

I climb in the driver’s side without a word, and she pokes one manicured finger into my bicep. “You know, you didn’t have to come. Tig overreacts. That’s all.”

“But you can’t drive, and God knows Pete won’t pick up, so it’s me.”

“Well,” she says reasonably, but it comes out like

Welllll.

“Pete has a family.” An accusation. I am less because I do not.

At her house, I pull up in the driveway. The garage door is caving in, the soffit sinking, rendering it useless. It’s been a few months since I’ve been back. I guide her inside and direct her upstairs, where she strips out of her clothes, leaving them tossed around the floor like a drunk college kid. I follow behind her and gather them up, smoky jeans and a white billowing, gauzy shirt. I roll it all up in a ball and shove it in her nearly empty hamper. All around the bathroom and bedroom, clothes are piled in bunches. There must be three loads of laundry alone on the floor. I gather it all together and push the mountain in front of the hamper.

Paula crawls into the creaking old bed and lies flat on her back, immediately closing her eyes. She pulls the covers up to her chin and keeps perfectly still, pretending to be asleep out of spite. She looks dead with her sickly pallor and whitish-blue rings around her eyes.

I kiss her forehead. Her lipstick feathers in all directions, caked in the lines around her mouth. She smiles, placated, and pats my hand.

“You might make a good mother one day, Kay-kay,” she whispers.

I flick off the light and leave the room, slipping the door shut behind me. Downstairs, I survey the kitchen. In the sink teeters a tower of plates and mugs that are surely days old, crusted and yellow. The countertop is dull with the residue of unknown substances, dotted with brown coffee rings. The lid to the trashcan lies on the floor next to the garbage, and a cinched bag sits on top of it. Next to the sink, a half-eaten apple is clouded with fruit flies. I pitch it in the trash, tie up the whole mess, and dump it out back.

I text a message to Scott:

Call me when you wake up. I’m at my mother’s. Story later.

I roll up my sleeves and let the hot water run over my hands until they scald. Using the abrasive back of a sponge, I scour the countertop, working in small circles until the sweat drips down the back of my neck, and I hear Paula’s whisper in my ear.

“You might make a good wife someday, too.”

I am twenty minutes late the next morning, and the empty chair to my right mocks me for the whole four-hour rehearsal. Amy Sung, third-chair violinist and the closest thing I currently have to a best friend, avoids me. She rosins her bow in a meticulous rhythm at breaks and speaks in hushed tones to Nikolai, the conductor. I try to catch her eye, but her gaze slides one way, then the other, off to the side, or unfocused against the far wall. I feel it. She’ll compete. She’s auditioning, too. I am the natural choice: I have the years of experience. Although I’m young, I have the technical expertise. I’m already assistant concertmistress. But nothing is guaranteed. My stomach pits.

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra has low turnover. It’s the full stop at the end of a long, winding career filled with teaching positions and lesser orchestras. There’s nowhere else to go. Except first chair. Concertmistress. In my six-year term, I’ve seen that first chair empty one time, for four days. Until Lesley Maxx.

Lesley played in the TSO for fifteen years, and her retirement was expected—celebrated, even. Most professional musicians retire long before sixty, but Lesley stayed sharp and quick with the bow. Her eyesight and ear never wavered. When I asked her why she was leaving, she patted my shoulder. “Always leave when you’re ahead. The alternative is pity.”

I attended the banquet. As the assistant concertmistress, I gave a speech, appropriately teary, for the woman who had become my mentor. I cried when we hugged. She tucked a lock of hair behind my ear, kissed my cheek, and whispered, “It’s all done. You’re a shoo-in.” I assume she spoke to Nikolai. She spent the banquet night guiding me through the crowd. “Have you met Karen? She’ll be my replacement.” And those within earshot laughed good-naturedly. She was serious, though they didn’t know that. They thought she was being tongue in cheek, tossing it out of the side of her mouth like a vaudeville joke. Sure, I’d have to audition, but what Lesley said went. The queen speaketh. The minions obey.

Even Nikolai kowtowed to Lesley, who had twenty years’ experience on the next senior member of the TSO. She had demands, and he’d grudgingly scramble to meet them with ineffectual mumblings. She might have been a diva, but she drew a crowd. If Lesley said I was her replacement, I was. Easy peasy.

“Am I good enough?” I’d questioned only once, and she’d rapped the top of the music stand with her heavily ringed hand and brayed, a snort of rough air from the back of her throat.

“You’re better than you think, and that’s your biggest problem.”

In music—like most things, but somehow, I thought, especially music—a lack of confidence could kill you. It renders your notes weak, your timing off as you second-guess yourself, kills your passion. Anxiety was a known exterminator of all things passionate.

My confidence with the bow, even after almost twenty years of training, was a subject of discussion. Nikolai, Lesley, Amy, everyone has opinions, things I should or shouldn’t do. Have faith in myself. Play for a recording. Audition for a solo. I have a tendency to end weakly, the sound lilting and dipping to its final conclusion. I’m easily thrown by an imperceptible squeak, a periodic eighth beat, a too-late entrance. I routinely have trouble recovering.

“A concertmistress must, above all, lead,” Lesley admonished me time and time again. My neck and ears burned.

I am chased by one sinking, sickening thought:

I’m not good enough, and I have no idea why.

I fumble through rehearsal, nerves skittering across my knuckles at the pending audition. My end notes are weak, sputtering, and insecure. My hand moves woodenly, not fluid, and I shake my wrist out between pieces. My eyes burn, thick and sandpapery behind the lids.

“Are you okay?” Amy taps my shoulder. Those are the first words she’s spoken all rehearsal.

“I’m fine. I had to go get my mom at Tig’s.” I press the pads of my thumb and forefinger into my eye sockets, and the pressure, for a moment, serves as a relief valve.

“Again? You just got her, what? Two weeks ago?” She forgets to be weird, or whatever game she was playing before, I suppose the one where she doesn’t tell me she’s going to audition against me in an hour.

“Three. Yes. No one calls Pete. He has a family. He doesn’t answer. I

do

answer. Ergo, Tig calls me. Every time.” I take a long drink of water, and Amy leans her violin against her shoulder and gives me an awkward one-armed hug.

“I’m sorry, Kar. Can I do anything?” She pauses then picks at her thumbnail.

“Are you going to audition for concertmistress?” Being tired sometimes makes me reckless, or at least less able to tolerate someone else’s bullshit.

She levels her gaze. “I am. It’s fair.”

I consider this. She’s right. Yet I clutch the edge of my chair until my knuckles turn white. I want to throw the bow. First, I want to snap it over my knee, and then I want to throw it, all wildly pinwheeling across the stage, held together by the hair alone. I want to see everyone gape and duck and whisper. I want to, for once, lose my shit. I want to be the one with problems, the one no one can rely on.

Instead I smile at her. I tell the truth, even as it hurts. “Sure. That seems fair.”

I have Lesley. Amy is older than me by five years, but she has less orchestra experience than I do. Besides, I’m a shoo-in, so says everyone.

In front of my stand, I feel the string of tension pulled tight across my shoulder blades. Every movement is forced and unnatural. I can’t help thinking it’s because I’m so damn tired. The back of my throat itches, and I fumble through the last movement. The piece I’m so familiar with, Bach’s

Partita No. 2 in D Minor,

seems foreign to me. The easy, light dips and valleys and skips feel heavy and drawn out. The melancholy lilt bends dense and slightly flat, even to my own ears. I overcorrect and cut a few notes short. Nikolai arches his eyebrows and sets his lips in a straight line.