White Pine (4 page)

Authors: Caroline Akervik

Tags: #wisconsin, #family, #historical, #lumberjack, #boy, #survive, #14, #northwoods, #white pine, #river rat, #caroline akervik, #sawmill accident, #white pine forest

Chapter Three

~ Heading North ~

Eventually, I must have fallen asleep. But it

didn’t seem like any time had passed at all before I felt a hand

shaking me awake.

“Sevy. Sevy, wake up. It’s time,” Ma

whispered trying not to wake up Peter and Marta. “Mr. Walsh will be

coming for you soon. Wash up and get dressed. I’m making some

tea.”

Slowly, I sat up, leaving my blankets behind.

I shivered in the cold air. Ma had a fire going, but it wasn’t

doing much in the way of warming the place yet. It was pitch black

outside. Winter with its short days was definitely coming. I made

my way over to the washstand. I braced myself to shove my hands

into the ice-cold water. But, to my surprise, I found the water was

warm. Ma must have heated it up on the stove for me. But then today

was an important day, the day I was to leave Eau Claire, alone, for

the first time in my entire life.

The main room was a little warmer than the

bedroom.

“I’m brewing the tea right now.” Ma worked at

the stove. “Your breakfast is almost ready.”

I nodded, distracted, thinking about what I

might of forgotten to pack.

“Morning, son,” said Pa. He was already

sitting in his big chair by the table. In the hazy light of the gas

lamp, he looked bleary-eyed, like he hadn’t slept real well either.

His mouth was closed in the thin, tight line that told me he was

hurting.

“Pa”

“Sevy, you have everything ready?” Ma

asked.

“Yup. My rucksack’s right by the door.”

“Good,” Pa said with a nod. “Dan Walsh will

be here come daylight. Isn’t that what he said?” Pa looked to

Ma.

“Yes, Gus. I told you what Edith Walsh told

me. Dan is delivering some tools near Mondovi. He’ll bring Sevy

that far and then he’ll help him find a ride north.”

“

Good,” Pa grunted. “Sevy, you’ll be in

a Daniel Shaw lumber camp within few days.

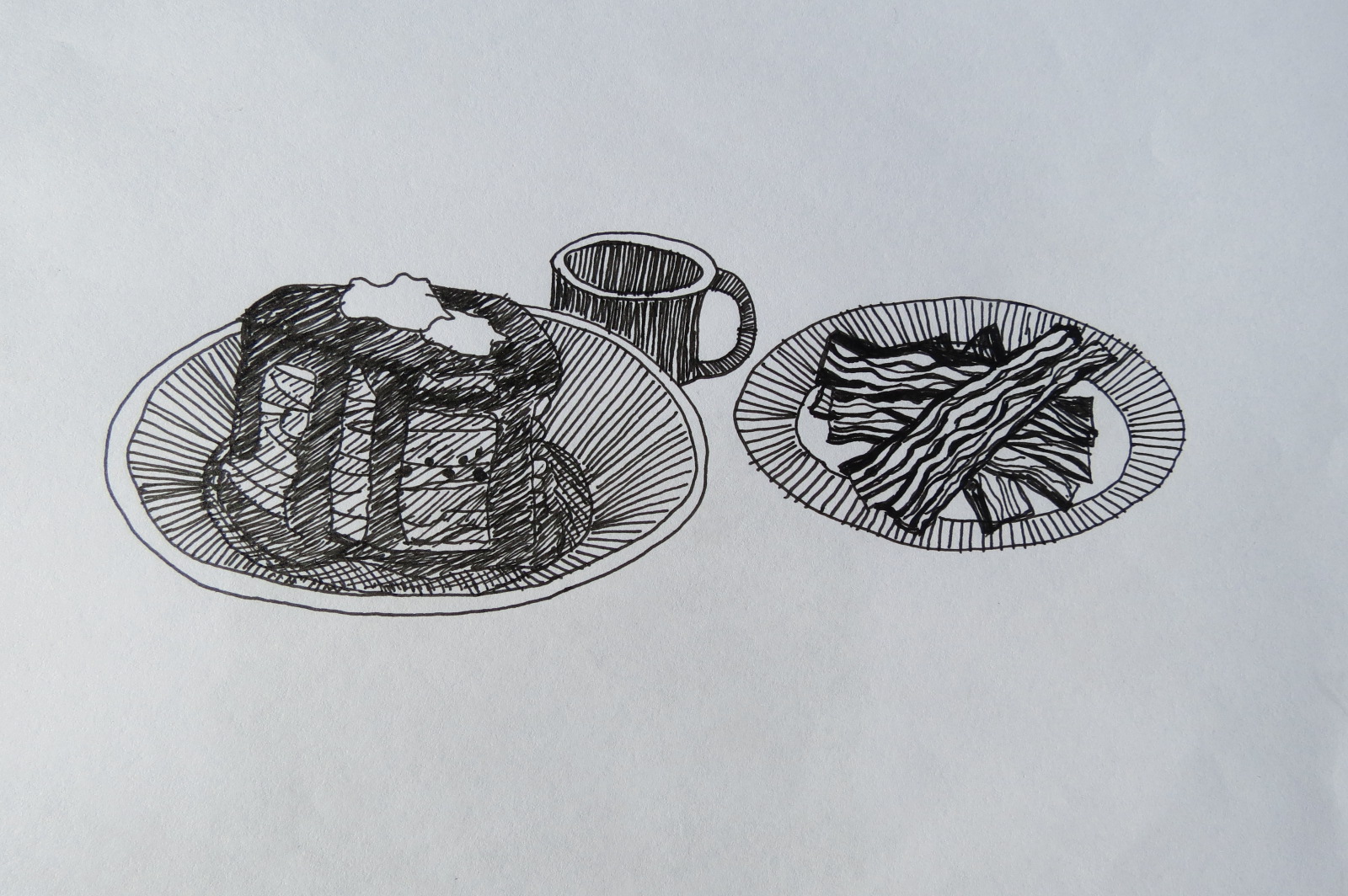

Ma placed a thick slab of bread with butter

and cheese melted on it in front of me. Next, she gave me a mug of

tea so hot that I had to set it down on the table. “Eat your

breakfast, Sevy. You don’t know when you’ll get your next hot

meal.”

As usual, I was starving. So, even with the

two of them sitting there watching me, I devoured all of my

breakfast.

Then Pa shoved his plate over to me. “I’m not

hungry, Sevy.”

I didn’t need much convincing and I was

licking the butter off my fingers when there was a soft knock at

the door. After some hurried hugs and kisses, some hastily

whispered words, I was wrapped up in a blanket on a wagon bound out

of Eau Claire. It was then that I realized I hadn’t said goodbye to

my little brother or sister. In all of the excitement, it had plumb

slipped my mind.

The next few days passed in a cold, hungry,

confused blur. At night, I slept in strange farm houses, eating

meals with folks I didn’t know. Days I spent cold and, more often

than not, wet riding in wagons north, always north. Eventually,

about a week after I left Eau Claire, I arrived at the lumber camp

that was to be my home for the next few months.

To be honest, the first time I saw that small

cluster of buildings, I wasn’t real impressed. I’d expected

something bigger, grander for the heroes of the Northwoods.

The fella driving the wagon spoke up, “Here

we are, boy.”

“Yup.” I nodded. “Thank you, mister.” I

couldn’t for the life of me remember his name. I’d ridden in so

many different wagons with so many different drivers over the past

few days.

The clearing was cut right into a white pine

forest. The rough hewn buildings were made of logs that had likely

been chopped down right here and they were set in a rectangle

around the clearing. I didn’t see anyone moving around, but that

made sense as it was the middle of the afternoon.

We pulled up to the biggest building. Almost

immediately, the door swung open and a thick set, red-faced man in

an apron stepped out.

“Harold,” the driver greeted the other

man.

“You have my flour?” he grumbled. “I had some

unhappy lumberjacks last night when I didn’t have any doorknobs for

them at supper.”

“Got a couple of bags for you.”

“Camp’s getting bigger every day. We need to

be stocked up for when the snows start to come. These mine?” He

reached under the oilskin and patted a burlap bag of flour.

“That whole pile is for you. No, not that

one. It’s for a Knapp, Stout, and Company camp that’s on a forty

north of here. And I brung you somethin’ else, too. See that

youngun over there.” He gestured at me with his thumb. “Him,

too.”

Harold eyeballed me, as if taking my measure.

Then, he spoke, “I’m Harold Hildreth, camp cook. Leave your gear on

the ground over there and help me get this flour into the

cookhouse.”

I jumped down from seat and did as I was

told. I tossed a fifty pounder of flour over my shoulder and

followed Harold into the building. We passed through the lean-to

and I saw a chest with a lock on it and a sign that read “Wanigan.”

Next, we stepped down into the main building. Here, despite the low

ceiling, I could stand up straight since the building was set into

the ground. Several large wooden tables filled the space and a

monster of a stove dominated the room. It was all clean as a

whistle and a rich meaty smell came from the cast iron pot set on

the stove. A skinny boy with sandy blond hair who looked to be

about my age was sitting in one corner peeling potatoes.

“Where do you want ‘em?” I asked.

“Just set them right there on the table,”

Harold said. “What’s your name, boy?”

“Sevy. Sevy Andersen.”

“I’m the cookee here,” the potato peeler

announced, glaring at me. “We don’t need no other boys. So you can

go right back to where you come from.”

“I’m not here to be a cookee,” I responded.

“I’m a lumberjack.”

Harold and the potato peeler burst out

laughing.

“No. Really. I’m here to be a lumberjack.” I

stared at him real hard and set my jaw. There was no way anyone was

gonna talk me out of a lumberjack’s pay. My family needed that

money. “Just ask Mr. Lynch. He’s the Push, right?”

“Rest assured, I’ll be talking to Joe,”

Harold responded. “But how did you end up here?”

“My pa’s Gus Andersen. He worked this outfit

last winter.”

“Gus is a good man. A hard worker and a heck

of a sawyer. I heard that he got hurt bad. How’s he doing?”

“Better.”

“How’s he getting around?”

“Crutches.”

Harold eyed me, clearly expecting me to say

more. “You’re a man of few words, like your Pa. Well, if you’re

gonna be lumberjacking this winter, we’re gonna have to feed you

up. Don’t ya think, Bart?” Harold chuckled at his own joke because

the potato peeler, Bart, was all skin and bones. Harold caught my

glance and chuckled. “I’m the best cook in this county. You shoulda

seen Bart a month back.”

“I’d rather be a cookee than a jack any day,”

Bart snapped. “I eat good and I’m warmer than those men out in the

woods. The cook’s probably the most important man in this camp,

except’in the Push. And I’m learning to cook. By the time that I

leave this camp in the spring, I’ll be ready to be a camp cook in

my own right.”

“Now don’t go getting too big for your

britches, Bart. You’ve got a lot to learn yet.”

“That’s just fine,” I agreed, but there

wasn’t no way I would want to be a cookee. I was here in the

Northwoods to draw a man’s pay, a full dollar a day, as a

lumberjack.

“Well, boy.” Harold turned to me. “I can’t

just stand around here chewing the fat. I gotta get supper ready.

This here’s the cookhouse, as you can see. You’ll eat here twice a

day. Bart brings the grub out to where you’re working at midday.

You passed by the wanigan on your way in. That’s where you can get

some necessaries you might of forgotten or used up. Now, you’ll be

needing to meet the Push and Dob O’Dwyer, he’s the clerk. Bart, why

don’t you do the honors.”

Bart nodded, set down the potato he was

peeling, and wiped his hands on his apron.

“Don’t be dawdling, Bart. Those taters will

be waiting for you.”

Bart tugged off his apron and headed towards

me. “Come on.”

I followed him back out of the cookshack and

into the clearing around which all of the logging camp buildings

were arranged. Out in the cold air, I could smell the promise of

snow in the air.

“Lemme grab my gear.” I scurried over to

where I’d tossed it and Bart slouched after me.

“That there’s the filer’s shack.” Bart

pointed a thumb over to one of the smaller log buildings. “He’s a

grouchy codger, but he does a good job keeping the saw blades

sharp. But you probably already know all about how a logging camp

works, don’t ya? Your Pa being a jack and all. Usually, I take

church ladies who come to the camp around, give them the tour, and

they don’t know nothin’ about logging camps.”

I nodded, though, to be honest, I hadn’t

known exactly what a filer did. My pa was indeed a man of few

words, and when he was with Ma and us kids, more often than not, he

let us do the talking.

“That there’s the blacksmith shop.” Bart

gestured with his thumb at another log building right by the

filer’s shack.

“That big one there is the horse barn.

There’re two teamsters at this camp and a couple of fine teams of

Belgians. I get to drive one of them hay-burners to the woods when

the jacks are dinnering out. Cy’s his name, the horse I mean, and

he’s blind in one eye. But the jacks say he has a second sense for

when a tree is coming down. This here’s the clerk’s office.”

Bart knocked and a gruff voice called out,

“It’s open.” So, we strolled right in.

“Shut the door. You’re letting in the winter

with you, boyo.” The voice was kindly with an Irish lilt to it.

My eyes slowly adjusted from the brightness

of the out-of-doors to the dim lamplight and I saw two men. One

wore spectacles, had a kindly face, hair that was near white,

though he looked to be about Pa’s age, and was seated at a desk on

which was set an opened ledger. The other fella who was standin’

was tall, thick and broad with a dark head of hair and with a no

nonsense air to him.

Dropping my bag, I took my hat off to show

respect, the way that my ma had always taught me.

“Mr. Lynch,” Bart spoke up. “This fella’s

come to be a lumberjack.”

“My name is Sevy Andersen.” I supplied.

Lynch looked at me real hard. He didn’t smile

and his eyes were cold. “You Gus Andersen’s boy?”

I nodded.

“You have the look of him.”

I nodded again.

“The boy doesn’t have much to say.” The

Irisher observed.

“Talked just fine in the cookhouse,” Bart

mumbled.

“Some of these Norwegian fellas can be tight

lipped. Why one of the fellas from last winter, I don’t think I

ever heard five words out of his mouth. Showed up one day with a

`Hello,’ and then left six months later with a `Goodbye.’” The

Irisher commented, as if that explained it.

“I ain’t full Norwegian. I’m half really, and

there ain’t nothin’ wrong with that. My Pa’s was one of the best

sawyers at this camp or at any of the other logging camps around

the Chippewa and he’s a full blooded Norwegian.” My voice cracked

on the last words.

“Well, you do talk,” the Irishman said with a

smile, as he put his pipe back between his yellowed teeth. “I

didn’t mean any disrespect, Sevy.”

Even Lynch was smiling now. But on his face,

a smile looked hard, like rock breaking. He nodded to me. “I’m Joe

Lynch and you can call me Mr. Lynch or Push. Your father said you

can do a man’s work in his letter. Is that true?”

“He looks kind of scrawny to me,” the Irisher

commented with his head tilted as he assessed me. “Tall, but

spindly.”

I began to panic. What if they didn’t give me

a chance? What if they decided that I was too young to draw a man’s

wage? My whole family was relying on me. I had to convince Joe

Lynch to let me stay on.

“I may be skinny, but I’m strong. And I’ll

work hard. Harder than anyone else here. I promise you, Mr. Lynch,

you won’t regret hiring me.”

“That’s quite a promise,” Lynch commented.

“And, I’ll hold you to it.” He held out his hand to me. “Your

father said much the same, and his word’s like gold to me. Welcome

aboard, Sevy.”

I took his hand. His palm was callused and

hard and he gripped my hand the way he might hold onto an axe. But

I gripped him right back, the way I’d been taught. The way a man

would. And even though he squeezed mine real hard, I didn’t flinch

or try to beat him. Pa had taught me to have a firm grip, but he’d

also warned me that a man who tries to win a handshake wants to

show you who’s the boss. I already knew that Joe Lynch was the

boss, and I didn’t plan on giving him any grief.