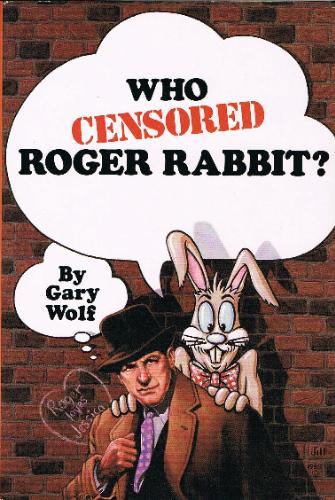

Who Censored Roger Rabbit?

Read Who Censored Roger Rabbit? Online

Authors: Gary K. Wolf

Gary K. Wolf

Copyright © 1981 by Gary K. Wolf

For information, write: St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Wolf, Gary K. Who censored Roger Rabbit? I. Title.

PS3573.0483W5 813’.54 81-8861

ISBN 0-312-87001-9 AACR2

Design by Laura Hainmond

10 987654321

First Edition

To Bugs, Donald, Minnie, and the rest of the gang at the B Street Smoke Shop

I found the bungalow and rang the bell.

My client answered the door.

He was almost my height, close to six feet, but only if you counted his eighteen-inch ears. He wore only a baggy pair of shorts, held up by brightly colored suspenders. His shoulders stooped so badly, he had to secure his suspender tops in place with crossed pieces of cellophane tape. For eyes, he had twin black dots, floating in the center of two oblong white saucers. His white stomach, nose, toes, and palms on a light brown body made him resemble someone who had just walked face first into a freshly painted wall.

“I’m Eddie Valiant, private eye. You the one who called?”

“Yes, I am,” he said, extending a fuzzy white paw. “I’m Roger Rabbit.” His words came out encased in a balloon that floated over his head.

The rabbit ushered me into his living room. The angular furniture reminded me of the upward-reaching spires in caves. That, combined with an extremely low ceiling and stale air, gave the room the closed-in nature of an underground burrow. Perfect interior design for a rabbit.

The bunny opened a liquor cabinet and brought out an earthenware jug emblazoned with three X’s. “Drink?” he asked.

Since ‘toons could not legally buy human-manufactured liquor, most drank the moonshine produced by their country cousins in Dogpatch and Hootin’ Holler. Potent stuff. Few humans could handle it.

Although no stranger to strong drink, I knew my limitations well enough to pass.

“Mind if I do?” the rabbit asked.

“Fine with me,” I said.

The rabbit cradled the jug in his elbow and guzzled down a healthy swig. Almost instantly, twin puffs of smoke shot out of his ears, drifted lazily upward, and bounced gently against the ceiling.

Quite nonchalantly, the rabbit pulled a large butterfly net out from behind the sofa, snared the bobbling whiffets, and shook them free through an open window. They joined forces, floated merrily skyward, and expanded into a soft, billowy cloud.

“Cumulonimbus,” the rabbit remarked, as he watched the evidence of his indulgence drift away.

The rabbit closed the window and drew the drapes to protect his frail parchment skin from the drying effects of the early morning sun. He hippity-hopped across the room to his desk, returned, and handed me a check. “A retainer. I hope it’s large enough.”

It certainly was! At my regular rates, the check would buy my services for nearly a week.

“Maybe I’d better outline my problem,” said the rabbit. “I know all the cash in the world wouldn’t persuade a private eye to take on an unjust cause.”

I nodded. If the rabbit only knew. I had undertaken numerous unjust causes in the course of my career, and for a lot less than all the cash in the world. A lot less.

The rabbit picked a walnut-inlaid cigar box off a mushroom-shaped coffee table. “Carrot?” he asked.

I looked inside. Sure enough, carrots, carefully selected for uniformity of color, size, and shape, and alternated big end to little end so that the maximum number of them could be squeezed inside. Each bore a narrow, gold and red paper band proclaiming it a product of mid-state Illinois, generally acknowledged as the world’s finest source of the orange nibblers.

I declined.

The rabbit selected a chunky specimen for himself and gnawed at it noisily, freckling his chin with tiny orange chips that flaked off in the gap between his front incisors. “About a year ago, the DeGreasy brothers, the cartoon syndicate, told me that if I signed with them they would give me my own strip.” He laid his half-eaten carrot on an end table beside a display of framed and autographed photos, some human, some ‘toon. They included Snoopy, Joe Namath, Beetle Bailey, John F. Kennedy, and, in a group shot, Dick Tracy, Secret Agent X-9, and J. Edgar Hoover. “Instead they made me a second banana to a dopey, obese, thumb-sucking sniveler named Baby Herman.”

“So find yourself another syndicate.”

“I can’t.” The rabbit’s face collapsed. “My contract binds me to the DeGreasys for another twenty years. When I asked them to release me so I could look for work elsewhere, they refused.”

“They give you any reason?”

“None. Being somewhat an .amateur private eye myself, I did some legwork.” He displayed a hind limb that would have looked exceptionally good dangling from the end of a key-chain. “I nosed around the industry and uncovered a rumor that someone wants to buy out my contract and give me a starring role, but the DeGreasys refuse to sell. I want you to find out what’s going on. If the DeGreasys won’t star me, why won’t they deal me away?”

Sounded horribly boring, but one more look at his check convinced me to at least go through the motions. I hauled out my notebook and pen.

Normally I would have asked some questions about his background and personal life but, since I only intended to give this case a lick and a promise anyway, why bother? I asked for the DeGreasys’ address, and he rattled it off.

“I’ll stay in touch,” I promised on my way out.

“See you in the funny papers,” joked the rabbit.

I didn’t smile.

I stopped off at a newsstand and bought a candy bar for lunch and a paper to read while I ate it, making sure to get a receipt for my expense report. I turned to the comic section and found the Baby Herman strip.

The rabbit appeared in one panel out of the four, barely visible behind the smoke and flame of an exploding cigar given him by Baby Herman.

I folded the paper shut. Hardly an earthshaking caper, this one. A fast buck and not much more. But what did I expect? Hobnobbing with a rabbit only gets you to Wonderland in fairy tales.

I met the DeGreasy brothers, Rocco and Dominick, in their offices high atop one of L.A.’s most prestigious skyscrapers.

The two were human, although almost comical in their marked resemblance to one another. Their ridged foreheads formed a wobble of demarcation between bowl-shaped haircuts and frizzy eyebrows. Their noses would have looked perfect behind a chrome horn bolted to the handlebars of a bicycle. Smudgy moustaches curtained their circular porthole mouths. Their biceps looked to be barely half the size of their forearms. And they had feet large enough to cut fifteen seconds off any duck’s time in the hundred-meter freestyle.

Had the DeGreasy boys been discovered frozen beneath some Arctic tundra, a good case would probably have been made for their being the long-sought missing link between humans and ‘toons.

But, as funny as they looked, when I checked them out, they had come up professional and efficient, the most astute guys in the comic-strip business. I gave my card to Rocco, the eldest, who passed it across his handsome antique desk to his brother Dominick.

Not wanting to spend a minute longer than necessary on this case, I came straight to the point. I told them Roger Rabbit had hired me to find out why they refused to honor their contractual obligation to star him in a strip of his own.

Rocco chuckled, then scowled, the way a father might when he sees his youngster do something irritating but cute. “Let me explain our position with regard to Roger Rabbit,” he said, without the slightest trace of rancor. His precise manner of speech and his six-bit vocabulary gave me quite a surprise. From his looks, I expected Goofy, but got Owen Cantrell, Wall Street lawyer, instead. “My brother Dominick and I signed Roger specifically because we felt he would play well as a foil for Baby Herman. We never made any mention of a solo strip then or since.”

Rocco leaned toward me, displaying in the process an impressive array of his stars’ merchandising tie-ins—a Superman tie bar, Bullwinkle Moose cufflinks, and a Mickey Mouse wristwatch. “Roger frequently concocts absurd stories such as this one. We tolerate his delusions because of his great popularity with his audience. Roger makes a perfect fall guy, and his fans love him for it. However, he does not have the charisma to carry a strip of his own. We never even considered giving him one. Right, Dominick?”

Dominick’s head bounced up and down with the vigor of a spring-necked plastic dog.

Rocco got up, opened a file drawer, and pulled out a sheaf of papers, which he handed to me. “Roger’s contract. Read it through. You’ll find no mention of a solo strip. And it stipulates a very generous salary, I might add.” He closed the drawer and returned to his chair. “We have treated Roger fairly and ethically. He has no reason whatsoever to complain.”

I flipped through the contract. It seemed to be in order. “What about the rumor going around that somebody wants to buy out Roger’s contract and make him a star?”

Rocco and Dominick exchanged quizzical glances and shrugged more or less in unison. “News to us,” said Rocco. “If someone did approach us with an offer for Roger, if it made financial sense, and if Roger wanted to go, we would gladly sell him off. We’re not ones to stand in the way of our employees’ advancement, and there’s certainly no shortage of rabbits to replace him.”

He stood and ushered me to the door. “Mister Valiant, I suggest you consider this case closed, and next time get yourself a more mentally stable client.”

Sounded reasonable to me.

I took a few random jogs. The trench coat, broad-brimmed hat, and large sunglasses matched me move for move.

A tail.

I picked up my pace, turned a corner, and ducked into a doorway.

Seconds later my tail came around the corner after me.

I let him get three paces past, then jumped him, grabbing his arm. I twisted it behind his back and slammed him against the nearest wall.

“Who are you, and what do you want?” I hissed, applying some persuasive pressure.

“I was only curious about how a real detective operates,” read my tail’s balloon. “I just thought I’d tag along. Kind of observe from a distance. I’m sorry if I fouled up your modus operandi.”

I released my grip, and snatched away the broad-brimmed hat, exposing a set of carefully accordioned eighteen-inch ears. “Look,” I told the rabbit, honing the hat against his concave chest, “when I have something worthwhile to report, I get in touch. Otherwise you stay away from me. Clear?”

The rabbit smoothed out his ears. However, the left one sprang back into a tight clump giving his head the lopsided appearance of a half-straightened paper clip. “Yes, I understand.” He fiddled with his ear, fiddled with his sunglasses, fiddled with the buttons on his trench coat, until finally he ran out of externals and began to fiddle with his soul. “My entire life I’ve wanted to be a detective.”

Sure. Him and ten million others. ‘Toon mystery strips suckered them into believing that knights-errant always won. Yeah, maybe Rip Kirby bats a thousand. But I consider it great if I go one for ten. “Forget it,” I said. “Besides, I’m not so sure how much longer I’m going to stay on this case.” I reported my conversation with the DeGreasys, adding that they’d suggested him as poster boy for the Failing Mental Health Society.

He took it in stride. “I never said they put in writing that bit about me getting my own strip,” he countered. “They made the offer verbally, and Rocco repeated it several times since.”

“Anybody besides you ever hear him?”

“Sure. He said it once at a photo session in front of Baby Herman and Carol Masters, my photographer. Just ask them. They’ll remember. As for my being crazy, yes, I see a psychiatrist, but so do half the ‘toons in the business. That hardly qualifies me as a full-blown looney.”

“I don’t know,” I said, figuring to cut it off here. “The whole mess sounds like a job for a lawyer.”

“Please,” the rabbit begged. “Stick with it. I’ll double your fee.”

Such persuasive words. “All right. You double my fee, and I stay on your case.” I turned and walked away.

The rabbit plopped his hat into the chasm between his ears and bounded after me, hopping so fast that his word balloons whipped across the top of his head, snapped loose with sharp pings at the base of his neck, and bounced off across the sidewalk. “Let me help you,” he said when he caught up with me. “It would mean a great deal to me. Please.”

“No way,” I stated flatly. “I work alone. Always have, always will.” Call me rude, but I say what I mean. If people want sympathy, let them see a priest.

At least he got the message. He did an abrupt about face and shambled away.

Apparently the strip business paid babies a whole lot better than it paid rabbits.

Baby Herman lived in an honest-to-God, balconied, marble-pillared, stone-lions-at-the-front-gate mansion tucked neatly away in the kind of neighborhood where middle-class rubbernecks ride bicycles on Sunday afternoons.