Whom the Gods Love (5 page)

Among the criminal classes, Peter Vance was known as Lighthouse Pete. This was on account of his nose, a large red efflorescence that seemed to have been attached to his otherwise pleasant face by mistake. It gave him the air of a genial drunkard, but Julian had never seen him the worse for liquor. He was actually very domestic, with a small wife and a large number of children tucked away in Camden Town. He was about forty, big and beefy, with blue eyes gleaming between narrow creased lids.

He arrived at Julian's flat in Clarges Street a little after eight o'clock. Julian brought him into the front parlour, which was the largest of the flat's three rooms and the one where he usually entertained. It was sparely but elegantly furnished, adorned with keepsakes he had picked up on his travels: a Moorish prayer rug, an astronomical clock, a Roman head of Venus with her nose slightly chipped. A fine pianoforte stood open, Rossini's latest score on the stand.

Vance eased his bulk into a seat by the fire, disposed of his hat under his chair, and laid a battered leather portfolio in readiness on his lap. Julian went over to a table where a Venetian decanter and glasses were set out. "Brandy?"

"Won't say no, sir."

Julian poured them each a glass, and they clinked rims.

Vance took a swig and grinned appreciatively. "Now this is something like, sir! It ain't every gentleman as'd have me into his parlour and give me some'ut to dip my beak in. Why, when I go to see one of your sort about a hire, sir, most times I ain't even asked to sit down."

"But I'm your colleague, not your client," said Julian, smiling. "It would hardly do for me to give myself airs."

"Now, that's very decent of you, sir—'specially seeing as how, for you, this is all sport. I mean to say, you don't make your living by it."

Julian knew what he meant: a gentleman would surely deem it beneath him to claim a share in the rewards for capturing Alexander's killer. In reality, Julian could have made good use of the money. But he could hardly compare his occasional difficulty paying his tailors with the struggle of a working man to support his family.

"You're right, of course," he agreed. "But you'll allow that, to a gentleman, sport is a very serious matter."

"And it does you credit, sir!" Vance said heartily. "Well now, sir: where would you like to begin?"

"I suggest we start with the events leading up to the murder. Assume I know nothing about it—which is very nearly true—and tell me all you've learned about Alexander Falkland's last night on earth."

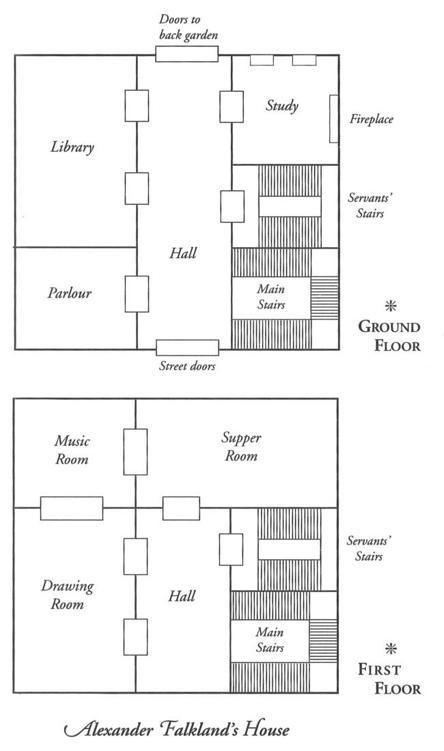

"Right, sir." Vance untied the strings of the portfolio in his lap. "I've got everything here: reports of the inquest, newspaper stories, my own notes. And I've culled out the most important witness statements, so you can read 'em now and get the flavour of things. I'll set the scene a bit first, if I may. On the night of Friday, April the twenty-second, Mr. and Mrs. Falkland gave a party at their house in Hertford Street. Now, the lay-out of the house is like this: kitchens in the basement; parlour, library, and study on the ground floor; public rooms on the first floor; bedrooms on the second floor. Bill Watkins—he's the patrol working with me—he's handy with his pencil, so I had him make a sketch of the ground and first floors. Here it is, sir."

Julian examined it. "I suppose the party took place on the first floor?"

"Yes, sir. Conversation and cards in the drawing room, entertainment in the music room, and a late supper in the supper room. All three rooms were got up with flowers and lights, and there were four musicians: a harp, two fiddles—violins, as

you'd

say, sir." Vance inclined his head, eyes twinkling. Hobnobbing with the Quality obviously amused him. "And a big fiddle—what's it called?"

"A violoncello?"

"Right, sir. Now, the party was to start at nine o'clock, but I'm told nobody comes to these set-outs on time."

"My dear fellow," said Julian, in his best drawing-room drawl, "punctuality is for people so vulgar as to have

appointments.

"

Vance chuckled. "Anyhow, the first guests arrived around ten, and nearly all of 'em had come by eleven. There were about eighty—all swells of one kind or another. Now for the witnesses' statements. They're a bit stilted, on account of being written up from answers to questions the magistrates put, but the clerks did pretty well at taking 'em down in just the words they used. Here." He handed Julian some papers tied together with a ribbon. "You can't do better than to start with Mr. Quentin Clare."

Quentin Clare was a fellow law student of Alexander's at Lincoln's Inn. Alexander had taken a fancy to him—no one could fathom why, for they could not have been less alike. Julian knew Clare slightly from Alexander's parties: a pale, thin, awkward young man, dressed in ill-fitting evening clothes and looking as if he wished very much he were somewhere else. "His statement is quite long."

"He had a sight more to say than any of the other guests. Just happened to be on the scene for everything important that went on."

Julian cocked an eyebrow. "That strikes you as suspicious?"

"You've got his statement, sir. You can judge for yourself."

STATEMENT OF QUENTIN CLARE, ESQ.

My name is Quentin Clare. I live at No. 5, Serle's Court, Lincoln's Inn.

I attended Alexander Falkland's party on 22 April. I arrived at about eleven o'clock. Falkland greeted me. He seemed in good spirits. I saw very little of him after that, as he had so many guests. I did not see Mrs. Falkland at all. I was told she had retired from the party with a headache shortly before I arrived.

I remember nothing unusual in anyone's behaviour, apart from one episode. At about half past eleven, one of the young ladies was persuaded to sing. I believe she is reckoned a beauty, so there was a crush in the music room, with everyone wanting to get near her. Falkland and others retired into the drawing room to make more room. I was feeling the heat and slipped out into the circular hall at the top of the stairs. That was at about twenty-five minutes to twelve.

Julian frowned. "He's very precise about the time."

"Well, he seems like that sort of young man, sir. Conscientious, good memory, trying to get everything right."

"Or he knew in advance he was going to be asked. It's not the sort of thing a party guest usually thinks about."

I was alone in the hall at first, but after a few minutes, a woman came up the servants' stairs. She was about forty, stockily built, dressed very plainly in a dark gown with a cross around her neck. I've since been told she was Mrs. Falkland's maid, Martha Gilmore. She dropped me a brief curtsey and stood looking about.

Just then Luke, one of the footmen, came out of the drawing room. Martha spoke with him in an undertone.

I assume she asked him to fetch Falkland, because he went into the drawing room, and Falkland came out.

Yes, it was very unusual for a servant to summon him out of a party. Ordinarily his parties ran like clockwork, and nothing interrupted them.

David Adams came out of the drawing room behind Falkland and stood in the doorway. I don't know Mr. Adams very well. I believe he advised Falkland about his investments.

Falkland went up to Martha and said something like "You asked to see me? I hope your mistress isn't worse?" Then he looked peculiar. He stared at her, his eyes widened, and his breath seemed to come quickly. But it was only for a moment. He had great self-command and regained it almost at once.

Martha said Mrs. Falkland still had a headache and would not be coming down again. Falkland said, a bit dazedly, "Is that all you wanted to tell me?" She said yes, curtsied, and went out through the door to the servants' stairs. Mr. Adams, who was still behind Falkland in the drawing room doorway, looked after her, then looked at Falkland malevolently. I don't know how else to describe the expression in his eyes. Falkland did not look back at him. Perhaps he did not realize he was there.

Falkland seemed to see me for the first time. He came forward, smiling, and asked why I was out in the hall alone. He took my arm and brought me back into the drawing room. Mr. Adams slipped in just before us. He seemed not to want Falkland to know he had been listening.

When Falkland and I returned to the drawing room, people surrounded us, asking what Martha had wanted and whether Mrs. Falkland was very ill. Falkland said there was nothing to worry about—she merely had a persistent headache, which would prevent her from coming down again. He ought to look in on her, he said, and excused himself. That was some time between a quarter to twelve and midnight.

At about twenty minutes to one, I left the party again. I'd been feeling beleaguered. Falkland hadn't come back, and people were beginning to wonder why both he and Mrs. Falkland had disappeared from their own party. Rumours began to fly about. I should rather not repeat them.

(Witness was pressed for an answer.)

If you must know, people said Falkland and his wife had quarrelled, she'd gone to her room, and he was trying to persuade her to come back. Some of the guests seemed to think I knew more about it than I let on. I don't know why, except that Falkland and I were friends, and I had overheard his conversation with Martha. Lady Anthea Fitzjohn was especially persistent in questioning me. I'm afraid it's ungracious, but I wished to get away from her. I went into the hall again, took a candle from the sideboard, and went downstairs, meaning to read in the library until the supper was served at one.

I walked down the central hallway toward the library, which is on the left. The study is on the right. The study door had been left half open, and as the hall was quite dark, I could see a flicker of light inside. I thought someone must have left a candle burning and went in to put it out.

I saw

—

(Witness briefly overcome with emotion.)

I saw Falkland lying sprawled under one of the windows. His head was pushed up against the window seat, his right leg was crumpled under him, and his left leg was sticking out. There was a candle burning on the window seat above him.

I ran in and dropped down beside him. I was about to try to rouse him when I saw the wound in the back of his head. It was hideous. The poker from the fireplace was lying next to him. I realized that must be what had killed him. No, I didn't think about who might have done it. I was sick and dizzy, hardly able to think at all.

I tried to collect myself and felt for a pulse in his wrist and neck. There wasn't one, and his skin was turning cold. I ran out of the study and upstairs. I was about to go into the drawing room, but then I thought what a panic there would be among the guests. The supper room door was open, and I could see the butler and Luke making preparations for the supper. I went in and told them Falkland had been killed. I think they thought I was mad. I took them downstairs and showed them his body.

The butler was horrified and sprang toward it, but I said I thought we weren't supposed to touch anything.

Clare went on to describe how the butler took charge of everything: sent for Falkland's physician, got word to Bow Street, and appointed Martha to break the news to Mrs. Falkland. Clare returned to the party. The guests were more restless and bewildered than ever, but no one was inclined to leave till the mystery of Falkland's disappearance had been explained.

Suddenly we heard screaming from the floor above. It sounded like "No! No!" There was consternation. Guests poured out of the drawing room into the hall. Some of them started up the stairs, and Luke had to bar their way.

The butler restored a measure of order, Clare said. Soon after, Mrs. Falkland came downstairs and told the guests of her husband's murder.

Julian flipped back to the beginning of the statement. "He says Falkland seemed in good spirits that night, but since he also admits he didn't see much of him, he may not be any judge."

"The other guests say the same, though, sir. If Mr. Falkland thought he was in danger, he gave nary a sign of it."

Julian turned a few pages. "He says Falkland left the party between a quarter to twelve and midnight."

"Yes, sir. Most of the guests put it at just before midnight—ten minutes before at the earliest."

"What do we know about his movements after that?"

"Not a thing, sir. Except that he ended up in the study, where Mr. Clare found him. If anybody saw him in between, they ain't letting on."

"He said he was going upstairs to look in on Mrs. Falkland. Didn't she see him?"

"No, sir. Never saw him again after she left the party with a headache, which was about an hour earlier."

"Is it possible he looked in on her, but she was asleep?"

"She says not, sir. Says she was awake with her headache."

"Then we have Falkland leaving the party to go upstairs and see his wife, but instead going

downstairs

to the study. Why?"