Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective (12 page)

Read Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective Online

Authors: Geoffrey Beattie

Tags: #Behavioral Sciences

Figure 6.1

First trial: ‘Low Carbon Footprint’ vs ‘High Carbon Footprint’.

Figure 6.2

Second trial: ‘Good’ vs ‘Bad’.

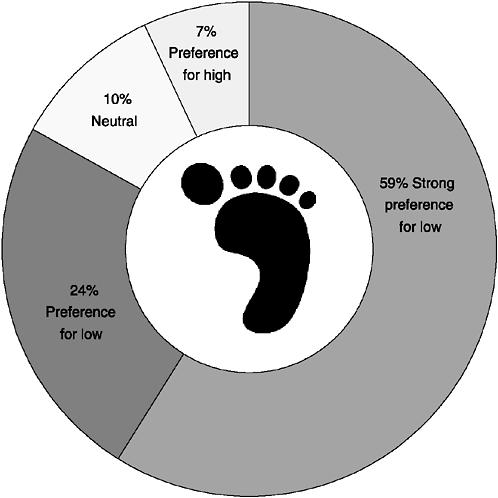

footprint. 10% of people were neutral, showing little or no preference for either high- or low-carbon-footprint products, and 7% showed an implicit preference for products with a high carbon footprint, as shown in

Figure 6.8

.

Put simply, implicit attitudes would seem to be even

Figures 6.3 and 6.4

Third and fourth trials: ‘Good or High Carbon Footprint’ vs ‘Bad or Low Carbon Footprint’.

Figure 6.5

Fifth trial: ‘High Carbon Footprint’ vs ‘Low Carbon Footprint’.

Figures 6.6 and 6.7

Sixth and seventh trial: ‘Good or Low Carbon Footprint’ vs ‘Bad or High Carbon Footprint’.

Table 6.4

D scores from the carbon footprint IAT

D Score | Type of preference | Percentage |

+0.8 | Strong preference for low carbon | 59% |

+0.5 | Medium preference for low carbon | 15% |

+0.2 | Slight preference for low carbon | 9% |

0 | No preference | 10% |

-0.2 | Slight preference for high carbon | 4% |

-0.5 | Medium preference for high carbon | 3% |

-0.8 | Strong preference for high carbon | 0% |

Figure 6.8

D score percentages.

more

biased towards low-carbon-footprint products than explicit attitudes. Overall 83% of participants showed some preference for low-carbon-footprint products compared to 70% or 67% on the earlier explicit measures. While our explicit measures suggested that 26% of our participants held neutral attitudes, the IAT measure suggested that only 10% of participants held a neutral view towards high- and low-carbon-footprint products.

What could possibly account for the decrease in the proportion of people holding neutral attitudes? I have one possible ‘methodological’ explanation for what is going on here. It could be due to participants showing positive implicit bias towards

specific

products and images whereas, of course, on the explicit measures, participants are forced to imagine an undefined set of products with either high or low carbon footprints and therefore participants may have sat on the fence more with these abstract concepts. It is a possible explanation.

Of course the IAT measures implicit attitudes to high-and low-carbon-footprint products

generally

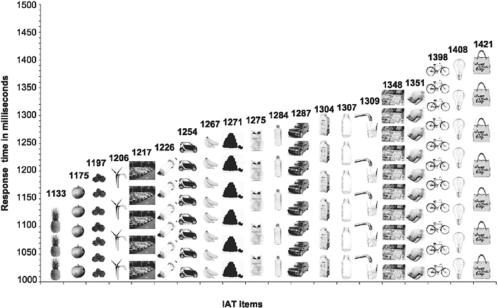

, but one can also focus on the response times to the different types of product used in the experiment and this does highlight some interesting differences between the products. By breaking down the overall response times into the individual mean response times for each picture item used in the IAT, we can gain an insight into how quickly our experimental participants categorised each individual item. This new focus reveals that certain food items, particularly fruit, are readily classified as having a high or low carbon footprint, suggesting that these items are easily automatically recognised as having either good or bad environmental characteristics. Pineapples (exotic, have to be transported great distances, therefore high carbon footprint, and therefore bad) were categorised most quickly of all, followed by English apples (low carbon footprint) and locally grown blackberries (low carbon footprint). The same is true for items representing certain energy sources (like wind) and modes of transportation (like cars). Oddly and somewhat counter-intuitively, the bicycle (the counterpoint to the car) took a lot of time to categorise.

It is only really within the past few years that packaging and the bags we use have been highlighted as a major environmental issue and an area where consumers can make a real difference, and the results showed that reusable carrier bags were the slowest to be categorised in this experiment. This result might surprise many people since the reusable bag has become such a symbol for whole sections of society who wish to flaunt their social identity as primarily concerned with green issues. It may act as a potent (and conscious and deliberate) social signal but it does not seem to have the same automatic, unconscious impact that some people might imagine. The results would seem to indicate that people need a little bit more time to process these iconic representations and assign them to one of two categories.

Similarly, our participants were quick to recognise that certain kinds of light bulb were good, but they took much longer to recognise that the alternatives (normal light bulbs) were bad. They also needed quite a lot of time to think about beef and chicken (the beef shown was high carbon footprint because cows generally have a higher carbon footprint than chicken and much beef comes from overseas).

Figure 6.9

shows the response times for each IAT item.

So what are the implications of all this? The implications would seem to be that people have the right attitude, both implicit and explicit (both conscious and unconscious) to low-carbon-footprint products. Since such attitudes, and their combination, set up a predisposition to act, then one might expect people to be doing much more for the environment in terms of their everyday supermarket shopping than they actually are. Green choices are becoming more popular, but not as quickly as some might have imagined. So there is clearly something else going on here, but what sorts of additional processes are critical here?

And something else is evident in these data, the first clear hint that people might say one thing but believe another. The research had shown that people, generally speaking, were very pro-low carbon in both their explicit and implicit attitudes, but a significant proportion of people showed a marked discrepancy between these two measures. They were

Figure 6.9

Response times to high- and low-carbon-footprint IAT items.