Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective (20 page)

Read Why aren’t we Saving the Planet: A Psycholotist’s Perspective Online

Authors: Geoffrey Beattie

Tags: #Behavioral Sciences

This reference to

dissociation

implies the existence of distinct structural representations underlying distinguishable classes of attitude manifestations. In psychology, appeals to dissociation range from the mundane to the exotic. At the mundane end, the dissociation label may be attached to the simple absence or weakness of correlation between presumably related measures. At the exotic end, dissociation may be understood as a split in consciousness, such as mutually unaware person systems occupying the same brain. (emphasis in original)

So how exotic is this dissociation in attitudes likely to be? There are a number of critical lines of evidence here. Nosek and Hansen (2008) report that in a meta-analysis of 81 studies the IAT was only moderately correlated with self-reported attitudes (

r

= 0.24; Hofmann, Gawronski, Gschwendner, Le and Schmitt 2005) and, in a study of fifty attitude domains, Nosek (2005) found that the strength of the correlation between the IAT and self-reported attitudes varied from near zero for some attitude domains (e.g. attitudes to thin and fat) to approximately 0.70 in other domains (e.g. pro-choice/pro-life attitudes). So in Greenwald and Nosek’s (2008) terms there is clearly at least a mundane dissociation between the two constructs. But, in addition, there is the finding that other variables (for example, chronological age) can have a well-defined relationship with one of the measures (say, explicit attitude) but no relation with the other (say, implicit attitude). This has been found for things like explicit and implicit age preference. Here, there is a significant correlation between the age of the participant

and age preference in the case of the explicit measure but no significant correlation in the case of the implicit measure.

Of course, these types of finding of possible attitudinal dissociation do not point to a single interpretation of the data, and Greenwald and Nosek (2008) have argued that they are, in fact, compatible with three different interpretations. First, the ‘single-representation hypothesis’, which maintains that the appearance of a dissociation is really just an illusion and all that is happening is that in explicit self-report measures, participants have the opportunity to modify their real response in their explicit reporting of their attitude. The second ‘dual-representation hypothesis’ is the real dissociation claim, and maintains that implicit and explicit measures of attitude have structurally distinct mental representations of attitudes and they are genuinely dissociated (see Chaiken and Trope 1999; Wilson, Lindsey and Schooler 2000). This hypothesis seems to be favoured by many in this area. Thus:

Abundant theory, and some evidence, point to the human mind being divided into two largely independent subsystems: first, a familiar foreground, where processing is conscious, controlled, intentional, reflective and slow, but where learning occurs rapidly; and second, a hidden background, where processing is unconscious, automatic, unintended, impulsive and fast, but where learning occurs gradually … This dual-process model is appealingly neat. It recalls Freud’s model of the mind, but with the inner sex maniac replaced by a dull but efficient zombie. (Gregg 2008:764)

In this hypothesis the implicit attitudes operate automatically and unconsciously (and have unconscious representations) while the explicit attitudes operate consciously and with deliberate thought (and have an underlying representation which is quite different).

The third ‘person vs culture hypothesis’ is that explicit measures capture the attitudes operating within a person while implicit attitudes represent the more general influence of what is known about a particular thing in a particular

culture. Nosek and Hansen (2008) argue, however, that the evidence from variations in the level of correlation in the IAT and self-reported attitude across individuals largely rules out this third hypothesis, and that the IAT does not merely reflect the evaluative judgement of the culture as a whole. Their conclusion is that the data demonstrate that the IAT is an individual difference measure and is associated with individual-level thoughts, feelings, and actions.

But that still leaves two major hypotheses: one (the single-representation hypothesis) is that there is one underlying representation for both implicit and explicit attitudes; the second is that implicit attitudes have their roots in the unconscious (dual-representation hypothesis) and explicit attitudes have their roots elsewhere. The first hypothesis might suggest that when we report our attitude we may be aware of what we really feel but we modify our verbal response particularly in sensitive domains (like race, attitudes to obesity and attitudes to green issues which we might like to exaggerate to make ourselves look good). The second hypothesis suggests that the implicit attitude is grounded in the unconscious; we are unaware of this attitude and may well be puzzled by the slowness of our reaction times and our high error rate when we sit in front of the computer screen as we complete the IAT.

This is clearly a major issue for social psychology and for those wishing to promote behavioural change in many core areas. For example, when we find using self-report measures that people seem to be pro-low carbon in explicit attitude (but not in implicit attitude), how should we interpret this result: as merely a social desirability effect or as something more profound? This could be extremely important from the point of view of behavioural change. One reason for saying this is that there are clear practical implications when the two attitudes align. As Greenwald and Nosek (2008) pointed out, ‘When self-report and IAT measures were highly correlated with each other – a circumstance occurring especially in domains of political and consumer attitudes – both types of measures were more strongly correlated with behaviour than when implicit– explicit correlations were low’ (2008:78). In other words,

once we know something about the nature of the correlation between these two measures, we will have a much better understanding of the likelihood of predicting behaviour from either or both of the measures. This is of major significance when it comes to climate change and how to tackle it.

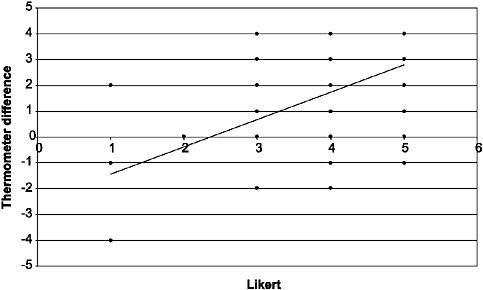

So, I returned to the original data to take a fresh look at the scores and I carried out a batch of statistical tests, and in particular a series of correlations to work out the relationship between the various measures. A Pearson product– moment correlation coefficient revealed that there was no significant correlation between any of the measures of explicit attitude and the IAT measure (for the Likert scores and

D

scores

r

= 0.008, for the thermometer difference scores and

D

scores

r

=-0.057). A Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient, however, showed that there was a strong positive relationship between the various measures of explicit attitude (namely, the Likert and thermometer difference scores,

r

= 0.560) as shown in

Figure 10.1

.

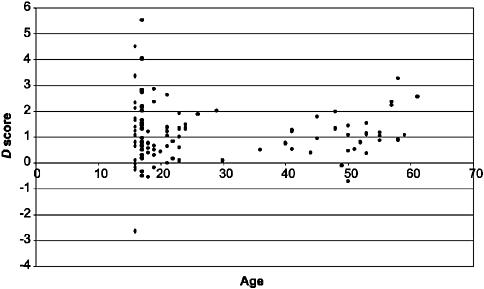

Further comparisons using a Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient suggested that while there was no relationship between age and

D

scores ( = 0.56) as shown in

= 0.56) as shown in

Figure 10.2

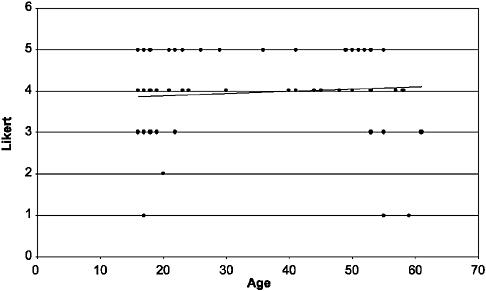

, there was a positive relationship between age and Likert scores ( = 0.214) as shown in

= 0.214) as shown in

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.1

Likert and thermometer difference correlations.

Figure 10.2

Age and

D

score correlations.

Figure 10.3

Age and Likert correlations.

and between age and thermometer difference scores ( = 0.197) as shown in

= 0.197) as shown in

Figure 10.4

.

In other words, the measures of implicit and explicit attitudes could well be dissociated because firstly there is no significant correlation between them, and secondly one additional variable (chronological age) correlates with one