Why the West Rules--For Now (20 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

In saying this I am not denying the reality of free will. That would be foolish, although plenty of people have succumbed to the temptation. The great Leo Tolstoy, for instance, closed his novel

War and Peace

with an odd excursus denying free will in history—odd, because the book is studded with agonized decisions (and indecisions), abrupt changes of mind, and not a few foolish blunders, often with momentous consequences. All the same, said Tolstoy, “

Free will is for history

only an expression connoting what we do not know about the laws of human history.” He continued:

The recognition of man’s free will as something capable of influencing historical events … is the same for history as the recognition of a free force moving the heavenly bodies would be for astronomy … If there is even a single body moving freely, then the laws of Kepler and Newton are negated and no conception of the movement of the heavenly bodies any longer exists. If any single action is due to free will, then not a single historical law can exist, nor any conception of historical events.

This is nonsense. High-level nonsense, to be sure, but nonsense all the same. On any given day any prehistoric forager could have decided not to intensify, and any farmer could have walked away from his fields or her grindstone to gather nuts or hunt deer. Some surely did, with

immense consequences for their own lives. But in the long run it did not matter, because the competition for resources meant that people who kept farming, or farmed even harder, captured more energy than those who did not. Farmers kept feeding more children and livestock, clearing more fields, and stacking the odds still further against foragers. In the right circumstances, like those prevailing around the Baltic Sea in 5200

BCE

, farming’s expansion slowed to a crawl. But such circumstances could not last forever.

Farming certainly suffered local setbacks (overgrazing, for instance, seems to have turned the Jordan Valley into a desert between 6500 and 6000

BCE

), but barring a climatic disaster like a new Younger Dryas, all the free will in the world could not stop agricultural lifestyles from expanding to fill all suitable niches. The combination of brainy

Homo sapiens

with warm, moist, and stable weather plus plants and animals that could evolve into domesticated forms made this as inevitable as anything can be in this world.

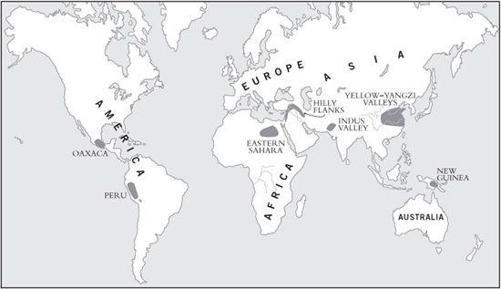

By 7000

BCE

the dynamic, expansive agricultural societies at the western end of Eurasia were unlike anything else on earth, and by this point it makes sense to distinguish “the West” from the rest. Yet while the West was different from the rest, the differences were not permanent, and across the next few thousand years people began independently inventing agriculture in perhaps half a dozen places across the Lucky Latitudes (

Figure 2.6

).

The earliest and clearest case outside the Hilly Flanks is China. Cultivation of rice began in the Yangzi Valley between 8000 and 7500

BCE

and of millet in north China by 6500. Millet was fully domesticated around 5500 and rice by 4500, and pigs were domesticated between 6000 and 5500. Recent finds suggest that cultivation began almost as early in the New World too. Cultivated squash was evolving toward domesticated forms by 8200

BCE

in northern Peru’s Nanchoc Valley and in Mexico’s Oaxaca Valley by 7500–6000

BCE

. Peanuts appear in Nanchoc by 6500, and while archaeological evidence that wild teosinte was evolving into domesticated corn in Oaxaca goes back only to 5300

BCE

, geneticists suspect that the process actually began as early as 7000.

The Chinese and New World domestications were definitely independent of events in the Hilly Flanks, but things are less clear in Pakistan’s Indus Valley. Domesticated barley, wheat, sheep, and goats all appear abruptly at Mehrgarh around 7000

BCE

—so abruptly that many archaeologists think that migrants from the Hilly Flanks carried them there. The presence of wheat seems particularly telling, because so far no one has identified local wild wheats from which domesticated wheat could have evolved anywhere near Mehrgarh. Botanists have not explored the region very thoroughly (not even the Pakistani army has much stomach for poking around these wild tribal lands), so there may be surprises in store. And while present evidence does suggest that Indus Valley agriculture was an offshoot of the Hilly Flanks, we should note that it rapidly went its own way, with local zebu cattle domesticated by 5500

BCE

and a sophisticated, literate urban society emerging by 2500

BCE

.

Figure 2.6. Promised lands: seven regions around the world where domestication of plants or animals may have begun independently between 11,000 and 5000

BCE

The eastern Sahara Desert was wetter around 7000

BCE

than it is now, with strong monsoon rains filling lakes every summer, but it was still a brutal place to live. Adversity was apparently the mother of invention here: cattle and sheep could not survive in the wild, but foragers could eke out a living if they herded animals from lake to lake. Between 7000 and 5000

BCE

the foragers turned themselves into pastoralists and their wild cattle and sheep into larger, tamer animals.

By 5000

BCE

agriculture was also emerging in two highland zones, one in Peru, where llama or alpaca were being herded and quinoa seeds were mutating to wait for the harvester, and one in New Guinea. The New Guinean evidence has been as controversial as that from the Indus Valley, but it now seems clear that by 5000

BCE

highlanders were burning off forests, draining swamps, and domesticating bananas and taro.

These regions have had very different histories, but, like the Hilly Flanks, each was the starting point for a distinctive economic, social, and cultural tradition that has lasted down to our own day. Here we can finally answer the question that has dogged us since

Chapter 1

, of how to define the West. We saw there the historian Norman Davies’s criticisms of what he called the “elastic geography” of definitions of the West, “designed,” as he put it, “to further the interests of their authors.” Davies threw the baby out with the bathwater, refusing to speak of the West at all. Thanks to the time depth archaeology provides, we can now do better.

The modern world’s great civilizations all go back to these original episodes of domestication at the end of the Ice Age. There is no need to let the intellectual squabbles Davies describes rob us of “the West” as an analytical category: it is simply a geographical term, referring to

those societies that descended from the westernmost Eurasian core of domestication, in the Hilly Flanks. It makes no sense to talk about “the West” as a distinctive region before about 11,000

BCE

, when cultivation began making the Hilly Flanks unusual; and the concept starts to become an important analytical tool only after 8000

BCE

, when other agricultural cores also started appearing. By 4500

BCE

the West had expanded to include most of Europe, and in the last five hundred years colonists have taken it to the Americas, the Antipodes, and Siberia. “The East,” naturally enough, simply means those societies that descended from the easternmost core of domestication that began developing in China by 7500

BCE

. We can also speak of comparable New World, South Asian, New Guinean, and African traditions. Asking why the West rules really means asking why societies descended from the agricultural core in the Hilly Flanks, rather than those descended from the cores in China, Mexico, the Indus Valley, the eastern Sahara, Peru, or New Guinea, came to dominate the planet.

One long-term lock-in explanation springs to mind immediately: that people in the Hilly Flanks—the first Westerners—developed agriculture thousands of years before anyone else in the world because they were smarter. They passed their smartness on with their genes and languages when they spread across Europe; Europeans took it along when they colonized other parts of the globe after 1500

CE;

and that is why the West rules.

Like the racist theories discussed in

Chapter 1

, this is almost certainly wrong, for reasons the evolutionist and geographer Jared Diamond laid out forcefully in his classic book

Guns, Germs, and Steel

. Nature, Diamond observed, is just not fair. Agriculture appeared in the Hilly Flanks thousands of years earlier than anywhere else not because the people living here were uniquely smart, but because geography gave them a head start.

There are 200,000 species of plants in the world today, Diamond observed, but only a couple of thousand are edible, and only a couple of hundred have much potential for domestication. In fact, more than half the calories consumed today come from cereals, and above all wheat, corn, rice, barley, and sorghum. The wild grasses these cereals evolved from are not spread evenly over the globe. Of the fifty-six grasses with the biggest, most nutritious seeds, thirty-two grow wild in southwest Asia and the Mediterranean Basin. East Asia has just six

wild species; Central America, five; Africa south of the Sahara, four; North America, also four; Australia and South America, two each; and western Europe, one. If people (in large groups) were all much the same and foragers all over the world were roughly equally lazy, greedy, and scared, it was overwhelmingly likely that people in the Hilly Flanks would domesticate plants and animals before anyone else because they had more promising raw materials to work with.

The Hilly Flanks had other advantages too. It took just one genetic mutation to domesticate wild barley and wheat, but turning teosinte into something recognizable as corn called for dozens. The people who entered North America around 14,000

BCE

were no lazier or stupider than anyone else, nor did they make a mistake by trying to domesticate teosinte rather than wheat. There was no wild wheat in the New World. Nor could immigrants bring domesticated crops with them from the Old World, because they could enter the Americas only while there was a land bridge from Asia. When they crossed, before the rising oceans drowned the land bridge around 12,000

BCE

, there were no domesticated food crops to bring; by the time there were domesticated food crops,

*

the land bridge was submerged.

Turning from crops to animals, the odds favored the Hilly Flanks almost as strongly. There are 148 species of large (over a hundred pounds) mammals in the world. By 1900

CE

just 14 of them had been domesticated. Seven of the 14 were native to southwest Asia; and of the world’s 5 most important domesticates (sheep, goat, cow, pig, and horse), all but the horse had wild ancestors in the Hilly Flanks. East Asia had 5 of the 14 potentially domesticable species and South America just 1. North America, Australia, and Africa south of the Sahara had none at all. Africa, of course, teems with big animals, but there are obvious challenges in domesticating species such as lions, who will eat you, or giraffes, who can outrun even lions.

We should not, then, assume that people in the Hilly Flanks invented agriculture because they were racially or culturally superior. Because they lived among more (and more easily) domesticable plants and animals than anyone else, they mastered them first. Concentrations

of wild plants and animals in China were less favorable, but still good; domestication came perhaps two millennia later there. Herders in the Sahara, who had just sheep and cattle to work with, needed another five hundred years, and since the desert could not support crops, they never became farmers. New Guinean highlanders had the opposite problem, with just a narrow range of plants and no domesticable large animals. They needed a further two thousand years and never became herders. The agricultural cores in the Sahara and New Guinea, unlike the Hilly Flanks, China, the Indus Valley, Oaxaca, and Peru, did not develop their own cities and literate civilizations—not because they were inferior, but because they lacked the natural resources.

Native Americans had more to work with than Africans and New Guineans but less than Hilly Flankers and people in China. Oaxacans and Andeans moved quickly, cultivating plants (but not animals) within twenty-five centuries of the end of the Younger Dryas. Turkeys and llamas, their only domesticable animals other than dogs, took centuries more.

Australians had the most limited resources of all. Recent excavations show that they experimented with eel farming, and given another few thousand years may well have created domesticated lifestyles. Instead, European colonists overwhelmed them in the eighteenth century

CE,

importing wheat and sheep, descendants of the original agricultural revolution in the Hilly Flanks.

So far as we can tell, people were indeed much the same everywhere. Global warming gave everyone new choices, among working less, working the same amount and eating more, or having more babies, even if that meant working harder. The new climate regime also gave them the option of living in larger groups and moving around less. Everywhere in the world, people who chose to stay put, breed more, and work harder squeezed out those who made different choices. Nature just made the whole process start earlier in the West.