Why the West Rules--For Now (38 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

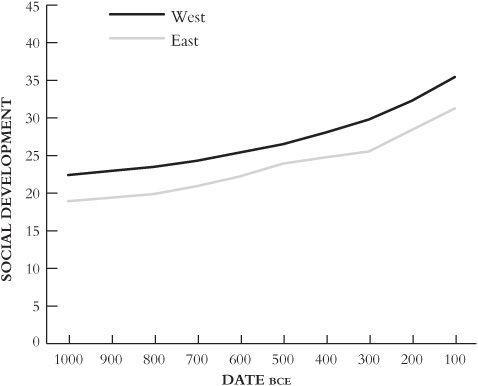

Figure 5.1. The dullest diagram in history? Social development, 1000–100

BCE

Why did the Western core not collapse around 700

BCE

, or the Eastern around 500

BCE

, when each hit twenty-four points? Why did social development rise so high by 100

BCE

? Why were the Eastern and Western cores so alike by this point? These are the questions I try to answer in this chapter, although the obvious follow-up questions—why, if social development was so high in 100

BCE

, did ancient Rome or China not colonize the New World? Or have an industrial revolution?—must wait till

Chapters 9

and

10

, when we can compare what happened after 1500

CE

and what didn’t happen in antiquity. Right now, though, we need to see what

did

happen.

KINGSHIP ON THE CHEAP

In a nutshell, the Eastern and Western cores avoided collapse in the first millennium

BCE

by restructuring themselves, inventing new

institutions that kept them one step ahead of the disruptions that their continuing expansion itself generated.

There are basically two ways to run a state, what we might call high-end and low-end strategies. The high end, as its name suggests, is expensive. It involves leaders who centralize power, hiring and firing underlings who serve them in return for salaries in a bureaucracy or army. Paying salaries requires a big income, but the bureaucrats’ main job is to generate that income through taxes, and the army’s job is to enforce its collection. The goal is a balance: a lot of revenue goes out but even more comes in, and the rulers and their employees live off the difference.

The low-end model is cheap. Leaders do not need huge tax revenues because they do not spend much. They get other people to do the work. Instead of paying an army, rulers rely on local elites—who may well be their kinsmen—to raise troops from their own estates. The rulers reward these lords by sharing plunder with them. Rulers who keep winning wars establish a low-end balance: not much revenue comes in but even less goes out, and the leaders and their kin live off the difference.

The biggest event in the first millennium

BCE

in both East and West was a shift from low-end toward high-end states. States had been drifting that way since the days of Uruk; mid-third-millennium-

BCE

Egyptian pharaohs already had enough bureaucratic muscle to build pyramids, and a thousand years later their successors organized complex armies of chariots. But the scale and scope of first-millennium-

BCE

states dwarfed all earlier efforts. The activities of states—management and fighting—therefore dominate this chapter.

Eastern and Western states took different routes toward the high end during the first millennium

BCE

, but both were bumpy. Eastern states, created so much later than Western ones, were still near the low end of the spectrum around 1000

BCE

. The Shang state had been a loose collection of allies who sent turtles and horses to Anyang and sometimes showed up for wars; and when King Wu overthrew the Shang in 1046

BCE

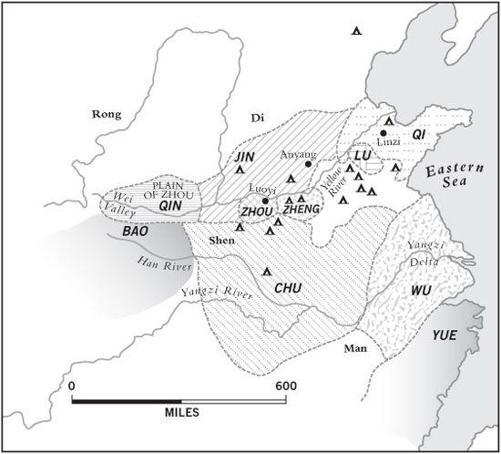

his Zhou state was perhaps even looser. Wu did not annex the Shang kingdom, because he had no one to run it. He simply put a puppet king over the Shang and went home to the Wei Valley (

Figure 5.2

).

This is a cheap way to control former enemies when it works, but in this case sibling rivalry, a perennial problem in low-end organizations,

soon undid it. Wu could not rely on his family to do what he wanted. He died in 1043

BCE

, leaving behind three brothers and a son. According to the Zhou dynasty’s official version, written of course by the winners, Wu’s son Cheng was too young to rule, so the Duke of Zhou, Wu’s younger brother, loyally agreed to serve as regent (many historians think the duke actually launched a coup). King Wu’s two elder brothers reacted by joining forces with the remnants of the Shang regime to resist the duke.

Figure 5.2. Low-end kingship in the East: sites from the first half of the first millennium

BCE

mentioned in the text. Triangles mark major Zhou colonies.

In 1041

BCE

the Duke of Zhou won this civil war and killed his elder brothers, but he realized he could neither rule the Shang as cheaply as Wu had hoped nor leave them to plot against him. He came up with a brilliant low-end solution: he would send members of the Zhou royal clan to set up virtually independent city-states along the

Yellow River valley (between twenty-six and seventy-three of them, depending on which ancient author we believe). These cities did not pay taxes to him, but he did not have to pay them to be there either.

The Zhou kingdom really was a family business—one that had much in common with that most famous of family businesses, the Mafia. The king, effectively the Zhou family’s

capo di tutti capi

, lived off huge estates in the Plain of Zhou, running them with a rudimentary bureaucracy, while his subsidiary rulers—“made men,” in the Mob’s terms—lived in their own fortified cities. When the king called on them, these lords provided him with muscle, showing up with chariots and troops so the king could shake down his enemies. When the fighting was over the mobsters shared the plunder and went home. Everyone was happy (except the plundered enemies).

Like bosses in

la cosa nostra

, Zhou kings offered emotional as well as material incentives to keep their captains loyal. In fact, they invested heavily in legitimacy, which is often the only thing that separates kings from gangsters. They convinced the subsidiary rulers that the king—as head of the family, master of divination and the ancestor cult, and the contact point between this and the divine world—had a right to call on them.

The more a king could rely on his kinsmen’s loyalty, of course, the less he had to rely on sharing plunder. Zhou kings actively promoted a new theory of kingship: that Di, the high god in heaven, chose earthly rulers and had bestowed his mandate on the virtuous Zhou because he was disgusted by the Shang’s moral failings. Stories about King Wu’s virtue grew so elaborate that by the fourth century

BCE

the philosopher Mencius was claiming that rather than fighting the Shang, Wu had merely proclaimed, “

I come

to bring peace, not to wage war on the people.” Immediately, “the sound of people knocking their heads on the ground [in submission] was like the toppling of a mountain.”

Few—if any—Zhou lords can have believed such silliness, but the mandate-of-heaven theory did encourage them to go along with the kings. It could also be turned on its head, though: if the Zhou ceased to behave virtuously, heaven could withdraw its mandate and bestow it on someone else. And who, if not the lords, was to say whether the kings’ behavior met heaven’s standard?

Zhou aristocrats liked to inscribe lists of the honors they received on the bronze vessels they used in rituals to honor their ancestors,

revealing nicely the combination of material and psychological rewards. One, for instance, describes how King Cheng (reigned 1035–1006

BCE

) “made” a follower in an elaborate ceremony, granting him his own lordship and lands. “

In the evening

,” the inscription says, “the lord was awarded many ax-man vassals, two hundred families, and was offered use of the chariot team in which the king rode; bronze harness-trappings, a dustcoat, a robe, cloth, and slippers.”

While it worked, the Zhou racket was highly effective. Kings mobilized quite large armies (hundreds of chariots by the ninth century

BCE

) and won general agreement that the ancestors wanted them to squeeze protection money from “barbarian enemies” who surrounded the Zhou world. Farmers within the Zhou realm, increasingly safe from attack, worked their fields and fed growing cities. Instead of taxing the farmers, the lords extracted labor dues. In theory, fields were laid out in three-by-three grids, like tic-tac-toe boards, with eight families working the outer fields for themselves and taking turns to work the ninth field, in the middle, for their lord. Reality was doubtless messier, but the combination of peasant labor, plunder, and extortion made the elite rich. They buried one another in spectacular tombs, and while they sacrificed fewer people than the Shang aristocrats, they buried far more chariots. They cast and inscribed astounding numbers of bronze vessels (some thirteen thousand examples have been excavated and published), and although writing remained an elite tool, it spread beyond its narrow Shang-era uses.

The system had one weakness, however; it depended on a steady diet of victories. The rulers delivered for nearly a century, but in 957

BCE

King Zhao failed. Failure was not something anyone wanted to write down, so all we know about it comes from a throwaway comment in the

Bamboo Annals

, a chronicle buried in a tomb in 296

BCE

and rediscovered when the tomb was plundered nearly six centuries later. It says that two great lords followed King Zhao against Chu, a region south of the Zhou realm. “

The heavens

were dark and tempestuous,” says the chronicler. “Pheasants and hares were terrified. The king’s six armies perished in the River Han. The king died.”

All at once the Zhou lost their army, their king, and the mystique of the mandate of heaven. Maybe, the lords apparently concluded, the Zhou were not so virtuous after all. Their problems compounded: after 950

BCE

inscriptions on bronze vessels found at the eastern end of the

Yellow River stop professing loyalty to the Zhou, and as the kings struggled to keep these vassals in line they lost control of “barbarian enemies” in the west, who began threatening the Zhou cities.

With the supply of newly conquered territories running low, elite conflict over land apparently increased. Faced with a meltdown in his low-end state, King Mu turned toward higher-cost solutions by building up a bureaucracy after 950

BCE

. Some Zhou kings (we aren’t sure which ones) then used their administrators to transfer land between families, perhaps to reward loyalty and punish betrayal, but the aristocracy pushed back. Piecing together the story from brief accounts on bronze vessels, it sounds like someone deposed King Yih in 885

BCE

, only for the “many lords” to restore him; and then Yih went to war with the greatest of these lords, Marquis Ai of Qi, boiling him alive in a bronze cauldron in 863. In 842 the “many lords” struck back, and King Li, like some Mob boss going to the mattresses as treacherous captains try to take him out, fled into exile.

At the other end of Eurasia, Western kings were also building low-end states in the tenth and ninth centuries

BCE

. How the Western core pulled out of its post-1200

BCE

slump is almost as unclear as how the slump began, but the inventiveness born of desperation probably played a part. The collapse of long-distance trade had forced people to fall back on local resources, but some vital goods—above all tin, essential for making bronze—were just not available in many places.

*

Westerners therefore learned to use iron instead. Smiths on Cyprus, which had long been home to the world’s most advanced metallurgy, had already figured out before 1200

BCE

how to extract a serviceable metal from the ugly red and black iron ores that crop up all around the Mediterranean, but so long as bronze was available iron remained merely a novelty item. The drying up of the tin supply changed all that, making it iron or nothing, and by 1000

BCE

the new, cheap metal was in use from Greece to what is now Israel (

Figure 5.3

).

Back in the 1940s Gordon Childe, one of the giants of European archaeology, suggested, “

Cheap iron

democratized agriculture and industry and warfare too.” Another sixty years of excavations has left us little clearer about exactly how this worked, but Childe was certainly right that iron’s easy availability made metal weapons and tools more

common in the first millennium

BCE

than they had been in the second; and when trade routes revived, no one went back to bronze for weapons or tools.