Why the West Rules--For Now (49 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

In the thousands of years since Old World farmers had started crowding into villages, they had evolved a nasty set of pathogens. Most were highly contagious; many could be fatal. Large populations breathing on one another and sharing body fluids spread diseases rapidly, but sheer numbers also meant that plenty of people happened to have the right antibodies to resist them. Over the millennia these people spread their defenses through the gene pool. Random mutations could still turn dormant diseases back into killers that would burn through the human population like wildfire, but hosts and viruses would then work out a new balance where both could survive.

People exposed for the first time to an unfamiliar package of germs have few defenses against the silent killers. The most famous example is what the geographer and historian Alfred Crosby has called the “

Columbian Exchange

,” the horrific, unintended fallout of Europe’s conquest of the New World since 1492

CE

. Entirely separate disease pools had evolved in Europe and the Americas. America had unpleasant ailments of its own, such as syphilis, but the small, rather thinly spread American populations could not begin to compete with Europe’s rich repertoire of microbes. The colonized peoples were epidemiological virgins. Everything from measles and meningitis to smallpox and typhus—and plenty in between—invaded their bodies when the Europeans arrived, rupturing their cells and killing them in foul ways. No one knows for sure how many died, but the Columbian Exchange probably cut short the lives of at least three out of every four people in the New World. “

It appears

visibly that God wishes that [the natives]

yield their place to new peoples,” one sixteenth-century Frenchman concluded.

A similar but more evenly balanced “Old World Exchange” seems to have begun in the second century

CE

. The Western, South Asian, and Eastern cores had each evolved their own unique combination of deadly diseases in the thousands of years since agriculture had begun, and until 200

BCE

these developed almost as if they were on different planets. But as more and more merchants and nomads moved along the chains linking the cores, the disease pools began to merge, setting loose horrors for everyone.

Chinese documents record that mysterious pestilences broke out in an army fighting nomads on the northwest frontier in 161–162

CE

, killing a third of the troops. In 165 ancient texts again talk of disease in the army camps; but this time the texts are Roman, describing pestilence in military bases in Syria during a campaign against Parthia, four thousand miles from the Chinese outbreak. Plagues returned to China five more times between 171 and 185 and ravaged the Roman Empire almost as often in those years. In Egypt, where detailed records survive, epidemics apparently killed more than a quarter of the population.

It is hard to figure out just what ancient diseases were, partly because viruses have continued to evolve in the past two thousand years, but mostly because ancient authors described them in such maddeningly vague ways. Just as aspiring writers today can buy books such as

Screenwriting for Dummies

then churn out movies or TV shows to formula, ancient authors knew that any good history needed politics, battles, and plagues. Their readers, like us when we go to movies, had a strong sense of what these plot elements should look like. Plagues needed omens of their approach, gruesome symptoms, and staggering death tolls; rotting corpses, the breakdown of law and order, and heartbroken widows, parents, and/or children.

The easiest way to write a plague scene was to lift it from another historian and just change the names. In the West the archetype was Thucydides’ eyewitness account of a plague that hit Athens in 430

BCE

. In 2006, a DNA study suggested that this was a form of typhoid fever, though that is not entirely obvious from Thucydides’ narrative; and after other historians had recycled his (admittedly gripping) prose for a thousand years, not very much at all is obvious about the epidemics they described.

Despite this fog of uncertainty, Roman and Chinese sources contrast sharply with Indian literature, which mentions no plagues in the second century

CE

. That may just reflect the educated classes’ lack of interest in something as mundane as the deaths of millions of poor people, but more likely the plagues really did bypass India, which suggests that the Old World Exchange spread mostly across the Silk Road and steppes rather than by the Indian Ocean trade routes. That would certainly be consistent with how the epidemics began in China and Rome, in army camps on the frontiers.

Whatever the mechanisms of microbial exchange, terrible epidemics recurred every generation or so from the 180s

CE

on. In the West the worst years were 251–266, when for a while five thousand people died each day in the city of Rome. In the East the darkest days came between 310 and 322, beginning again in the northwest, where (according to reports) almost everyone died. A doctor who lived through the sickness made it sound like measles or smallpox:

Recently there have been

persons suffering from epidemic sores that attack the head, face, and trunk. In a short time, these sores spread all over the body. They have the appearance of hot boils containing some white matter. While some of these pustules are drying up a fresh crop appears. If not treated early the patients usually die. Those who recover are disfigured by purplish scars.

The Old World Exchange had devastating consequences. Cities shrank, trade declined, tax revenues fell, and fields were abandoned. And as if all this were not enough, every source of evidence—peat bogs, lake sediments, ice cores, tree rings, strontium-to-calcium ratios in coral reefs, even the chemistry of algae—suggests that the weather, too, turned against humanity, ending the Roman Warm Period. Average temperatures fell about 2°F between 200 and 500

CE

, and since the cooler summers of what climatologists call the Dark Age Cold Period reduced evaporation from the oceans and weakened the monsoon winds, rainfall declined as well.

Under other circumstances, the flourishing Eastern and Western cores might have responded to climate change just as effectively as they had done when the Roman Warm Period began in the second century

BCE

. But this time disease and climate change—two of the five horsemen

of the apocalypse who featured so prominently in

Chapter 4

—were riding together. What that would mean, and whether the other three horsemen of famine, migration, and state failure would join them, would depend on how people reacted.

LOSING THE MANDATE OF HEAVEN

Like all organizations, the Han and Roman empires had evolved to solve specific problems. They had learned how to defeat all rivals, govern vast territories and huge populations with simple technologies, and move food and revenue from rich provinces to the armies on their frontiers and the crowds in their great cities. Each, though, did all this in slightly different ways, and the differences determined how they responded to the Old World Exchange.

Most important was how each empire dealt with its army. To confront the Xiongnu from the 120s

BCE

onward, the Han had developed huge cavalry squadrons, increasingly recruited from the nomads themselves, and as they perfected the “using barbarians to fight barbarians” policy in the first century

CE

they settled many of these nomads within the empire. This had the double consequence of militarizing the frontier, where Xiongnu fighters lived with little Han supervision, and demilitarizing the interior. Few troops were to be found in the heart of China, except at the capital itself, and fewer still were recruited there. Chinese aristocrats saw little to gain from serving as officers over “barbarians” stationed far from the capital. War became something that distant foreigners did on the emperor’s behalf.

The upside for emperors was that they no longer had to worry that powerful noblemen would use the army against them; the downside, that they no longer had much of a stick with which to beat any noblemen who did become troublesome. Consequently, as the state’s monopoly on force weakened, aristocrats found it easier to bully local peasants, swallowing their farms into huge estates that the landlords ran as private fiefdoms. There is a limit to how much surplus can be squeezed out of peasants, and when the landlord was so near and the emperor so far away, more surplus was handed over to local masters as rent and less sent to Chang’an as tax.

Emperors pushed back, limiting the size of estates aristocrats could hold and the number of peasants on them, redistributing land to free (and taxable) small farmers, and raising cash from state monopolies on necessities such as iron, salt, and alcohol. But in 9

CE

the emperor-landlord tussle turned critical when a high official named Wang Mang seized the throne, nationalized all land, abolished slavery and serfdom, and pronounced that from now on only the state could own gold. His near-Maoist centralization collapsed immediately, but peasant uprisings convulsed the empire, and by the time order returned, in the 30s

CE

, Han policy had gone through a sea change.

The emperor who replaced Wang Mang, Guangwu (reigned 25–57

CE

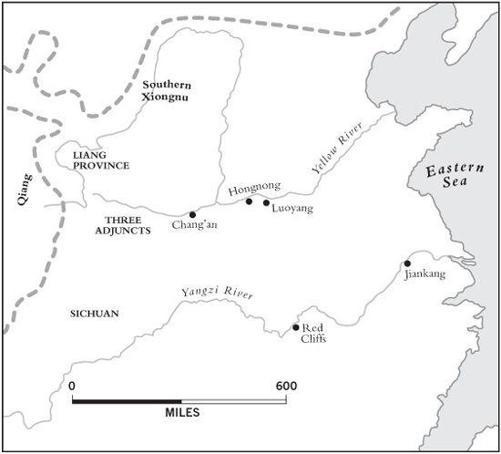

), came from a propertied family, not one that drew its power from links to the old court. To restore Han authority, Guangwu had to work closely with his fellow magnates, and he threw his lot in with them, initiating a golden age for landowners. Growing as rich as kings and ruling thousands of peasants, these grandees virtually ignored the state and its bothersome taxmen. Formerly Han emperors had moved troublesome landowners to Chang’an so they could keep an eye on them, but Guangwu instead moved the capital to Luoyang (

Figure 6.4

), where the landowners were strongest and the magnates could monitor the court.

*

The elite began rolling back the state and steadily disengaging from its biggest budget item, the army. By the late first century

CE

, with the Xiongnu no longer a major threat, the great cavalry army that had been built to fight them was being left to fend for itself, which meant plundering the peasants it supposedly protected. By about 150

CE

the Southern Xiongnu, theoretically vassals, were more or less independent.

Nor was much effort made to reshape the army to meet new threats being posed by the Qiang, a name the Chinese used loosely for farmers and herders around their western frontier. Thanks perhaps to the clement weather of the Roman Warm Period, Qiang numbers had been growing for generations and small groups had moved into the western provinces, occupying land when they could, fighting and stealing

when they could not. To keep this under control the frontier needed garrison troops, not nomadic cavalry, but the landowners of the Luoyang region did not want to pay for them.

Figure 6.4. The end of the Han dynasty, 25–220

CE

: locations mentioned in the text

Some officials suggested abandoning the western provinces altogether and leaving the Qiang to their own devices, but others feared a domino effect. “

If you lose

Liang province,” one courtier argued, “then the Three Adjuncts will be your border. If the people of the Three Adjuncts move inward, then Hongnong will be the border. If the people of Hongnong move inward, then Luoyang will be the border. If you carry on like this you will reach the edge of the Eastern Sea, and that, too, will be your border.”

Persuaded, the government stayed the course and spent a fortune, but infiltration continued. In 94 and again in 108

CE

Qiang groups took over broad swaths of the western provinces. In 110 there was a

general Qiang uprising, and by 150 the Qiang were as much beyond Luoyang’s control as were the Xiongnu. On both the western and the northern frontiers local landowners had to organize their own defenses, turning dependent peasants into militias, and the governors, forgotten by the state that had sent them there, also raised their own armies (and plundered their provinces to pay them).

It must have been hard not to conclude that the Han had lost the mandate of heaven, and in 145

CE

three separate rebellions demanded a new dynasty. For the great landowning elite, however, the cloud had a thick silver lining. The empire was smaller, tax receipts were dwindling, and the army was, in a sense, being privatized, but their estates were more productive than ever, imperial tax collectors left them alone, and war was but a distant rumor. All was, after all, for the best.

China’s Panglosses had a rude awakening when the Old World Exchange burst onto this scene in the 160s. Plagues ravaged the northwest, where the Qiang were moving into the empire, and spread across the land. And rather than responding with strong leadership, the imperial court imploded.