Why We Broke Up (16 page)

“Lottie Carson.” I stepped close to you, but you held your hands out, you weren’t done.

“And they’ll say things, right? I know they will, of course they will. Your friends are, probably, too, right?”

“

Yes

,” I said. I felt furious, or furiously

something

, pacing with you and waiting to fall into your moving arms.

“

Yes

,” you said, with a huge grin. “Let’s stay together, I want to be with you. Let’s. Yes?”

“Yes

.”

“Because I don’t care, virginity, different, arty, weird parties with bad cake, that igloo. Just

together

, Min.”

“Yes.”

“Like everyone is telling us not to be.”

“Yes!”

“Because Min, listen, I love you.”

I gaped.

“Don’t, you don’t have to—I know it’s crazy, Joan says I’ve really lost it, but—”

“I love you too,” I said.

“You don’t have to—”

“I’ve been wanting to,” I said, “say it. But everyone says—”

“Yeah,” you said. “Me too. But I do.”

“Yes,” I said. “I don’t care what they say about it, any word of what they say.”

“I love you,” you said again, and then you stopped and we went at it, laughing and hungry on the sofa with our mouths open in a long, desperate kiss, sliding off to the floor, which was hard,

ouch

, too hard without the cushions there. We were laughing. We kissed more, but it was uncomfortable on the floor.

“What happened to the cushions?”

“Joan did that too,” you said. “But fuck that and fuck her.”

I laughed.

“What do you want to do now, Min?”

“I want to try the Pensieri.”

You blinked. “What?”

“The liquor for the cookies,” I said. “I got it. I want to

try it.” I hoped you wouldn’t ask where I got it, and you didn’t, so I never told you.

“The liquor for the cookies,” you said. “OK. Yes. Where is it?”

I went and got it, no glasses, just twisted at the top until it was open and the strange rich smell was in my face, like wine but with something running through it, herbal or mineral, dazzling and weird. “You first,” I said, and handed it over. You frowned into the bottle, then smiled at me and took a slow swig and immediately spat it out down your T-shirt.

“Criminy!” you shrieked. “That is, what is that? It tastes like somebody killed a spicy fig. What’s in that?”

I was laughing too hard to answer. You grinned and threw off your T-shirt. “I don’t even want to touch it! Criminy, it’s on my pants!” You tried to pour the bottle into my shrieky mouth, spilled it on my top. I squealed and grabbed it, threatening Pensieri everywhere like a hand grenade, you undid your pants smiling, I felt the liquor sticky on my skin and put the bottle down, took off my shirt without unbuttoning it, a ripping sound, a button skittering under the television, heaving there in my bra, laughing at you struggling with the last bit of your jeans. I’ve seen

Now Calls the Wilderness

on the big screen, Ed, I’ve seen a fully restored print of

The Acrobats

. I have never seen anything so very beautiful as you in your underwear like a little boy, then naked, hooting with laughter, the drink a streak on your chest, excited,

looking at me in the living room. I kept that beautiful sight deep inside me, all the way home hours later, the Pensieri in the pocket of the coat I bought you, which you gave back to me because the weather had gotten cold and worse, wrapping me in what you’d never wear again, buttoning it so it might hide my ruined top, all the way home thinking of your laughing naked face. Nothing else came close. Not even what you managed to do with me later, breathless and open and flushed after I answered your next question, patient with your fingers and your mouth so warm on me I could not tell one from the other, what no boy could ever pull off because no boy asked so sweet and happily for help, as terrific and gasping as it was, not even that overcame the sight of you there laughing. I never told you that, even after telling you I love you, all those times all that day, I never told you how beautiful it was then, like everyone was telling us not to be. I never told you that, it was too tremendous a thing to tell until now in tears in Leopardi’s with my friend restored to me, just something to gaze at in the light of that gorgeous morning smiling at me smiling at you.

“And now, Min,” you asked me then in a pant, “what do you want to do now?” and I’m flushing now at what I said then.

Indelible

is the word the book uses,

When the Lights Go Down

, indelible images is what they keep saying. The brass mask of the emperor, floating faceup in the churning water before slowly sinking into black

in

Realm of Rage

. Patricia Ocampo’s sad, contemptuous gaze at the departing stagecoach in

The Last Days of El Paso

. Paolo Arnold screaming at the sky and carving the Sphinx. Bette Madsen’s legs they call indelible, the splits she does in

What a Hoot!

with those impossible stockings, the children playing as the assassin bleeds on the other side of the fence is indelible in

The Body Is a Machine (Le corps est une machine)

, the flying saucers in

The Flying Saucers!

indelible too. All it means is, I looked it up online to be sure, stays in your head. I’d only heard it about ink.

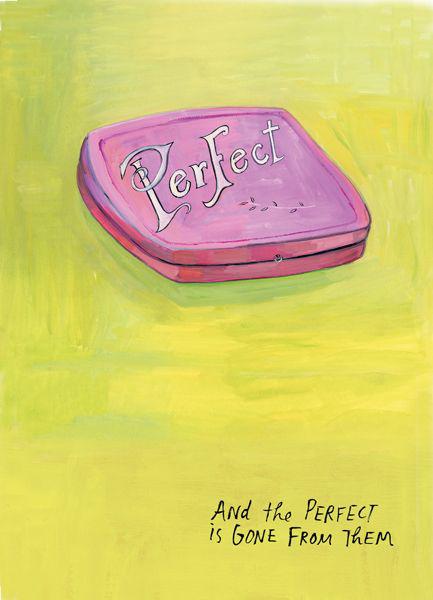

One I have is me in the empty band shell of Bluebeard Gardens. I can see it: I was wearing jeans, the green top you told me you like but probably couldn’t pick out of a lineup now, my black Chinese slippers falling off my feet, my sweater tied and drooping around my waist because it was sweaty to walk all that way from the bus. Sitting where they play the marches for the Fourth of July, where long-past-cool folk singers come to sing for free about overcoming injustice, just cold gray cement in the off-season, with dead leaves and the occasional squirrel in a frantic hurry. And me, sitting with my legs stretched out in a V, eating the pistachios your sister spiced and put in this elegant tin for you. It’ll never fade. It’s not what I saw—it’s not something I could have possibly seen—because we were together there, but when I see it, you’re not in the picture. In the indelible image, I am alone eating the pistachios and lining up perfectly the shells in half circles getting smaller and smaller like parentheses in parentheses. Really, you were just checking for electricity.

“There is,” you called happily from behind a pile of tarps, “a whole row of outlets here.”

“Working?”

“Should I stick my finger in them? I’m sure they’re

working. Who would turn them off? Enough for lights and music. Joan’s old boom box thing should do it, it’s ugly but loud.”

“And lights?”

“We have Christmas lights, but it’s a pain to get them. Do you have them somewhere better than our messy attic?”

I waited.

“Oh, right.”

“Right.”

“No Christmas for you.”

“No Christmas for me,” I said.

“But Hanukkah lights?” you said, bounding back to me. “They have those. I mean, it’s the Festival of Lights, right?”

“How do you know that?”

“I read about Jewish. I wanted to know.”

“Come on.”

“Annette told me,” you admitted, frowning a pistachio open. “But

she

read it someplace.”

“Well, I don’t have them. I’ll help you get them out of the attic. They’re not

too

Christmas-y, are they?”

“White, some of them are.”

“Perfect,” I said, and stretched my legs out further. You stood over me watching, munched, pleased.

“Is it?”

“Yes,” I said.

“And you laughed.”

“I didn’t

laugh

.”

“But you didn’t think of it,” you said, and did a few quick steps back and forth on the stage, athletic and cute. It was perfect, Bluebeard Gardens, fashioned crumbly and quaint like

Stage Door Kisses

or

And Now the Trumpets

. There were chairs down in the audience to sit in. Space for dancing, a platform where we could put the food. And out past the stage and the seats, the beautiful statues would keep stern and silent watch. Soldiers and politicians, composers and Irishmen, all along the perimeter, angry on horseback or proud with a staff. A turtle with the world on its back. A few modern things, a big black triangle, three shapes on top of one another, surely a spooky shadow at night. An Indian chief, nurses of the Civil War, the man who discovered something, the ivy too thick on the plaque to see, a test tube in his hand where birds had shat, a clipboard held at his side. Two women in robes representing the Arts and Nature, given to us from our sister city of somewhere in Norway. If we invited no one, it would still be a beautiful crowd of glamour, the commodore, the ballerina, the dragon for the Year of the Dragon 1916. I’d been here before as a kid for a few picnics, but my dad always said, I can hear him now, indelible, it was too loud. But without the hullabaloo it was the perfect, perfect place for Lottie Carson’s eighty-ninth birthday party.

“Are there cops here at night, I wonder,” I wondered.

“No.”

“How do you know?”

“Amy and I used to hang out here. She lived up on Lapp, just one block there. You can see the lions from her porch.”

“Amy?”

“Amy Simon. Sophomore year. She moved, her dad got transferred. Real asshole, that guy, strict and paranoid. So we used to sneak here.”

“So I’m not the first girl you’ve gotten naked in a park?” I said, smiling and thinking about this. I began to drop the shells one by one into this tin.

You looked up at the curve of the band shell for a sec,

perfect if it rains

, you’d told me. You’d thought of everything, you’d been thinking about the party, all by yourself. “You are, actually,” you said. “You’re the only one. But you’re not the only one I

tried

to get naked in a park.”

I laughed a little, dropped a few more in. “I guess I can’t blame you for trying.”

“No other girl,” you said. “Nobody else ever did anything but freak out if I mentioned any other girl.”

“I’m different, I know,” I said, a little bored of that.

“I don’t mean

that

,” you said. “I mean, I love you.”

Every time you said it, you really said it. It wasn’t like a sequel where Hollywood just lines up the same actors and hopes it works again. It was like a remake, with a new director and crew trying something else and starting from scratch.

“I love you too.”

“I can’t believe this is what you want.”

“What,” I said, “you?”

“No, I mean planning a party. Finding a park, just

showing

it to you, and you act like I did something.”

“You

did

. This

is

.”

“I mean, with my friends—we buy stupid things for our girlfriends.”

“Yeah, I’ve seen that around.”

“Teddy bears, candy things, magazines even. Don’t say it’s stupid, because we all think so, everybody, but it’s what we do. What do you guys do? Poems or something, right? I’m not going to write you a poem.”

Joe, actually, used to write me poems. Once, one of them was a sonnet. Those I gave back in an envelope. “I know. This is—I like

this

, Ed. This is a perfect place.”

“And I can’t buy you flowers, because we haven’t had a fight yet, really.”

“And I told you never to buy me flowers,” and I can see it, you rolling your eyes and smiling on the stage. I smiled back, an idiot who didn’t want flowers, the fucking flower shop where everything collapsed, why the bottom of this box is carpeted with dead rose petals like a shrine on the highway where there’s been a wreck.

“Do we have to go?”

We were skipping, but I had a test. “We have time, a little.”

“Gosh,” you said, “what can me and my girlfriend do in a park—”

“Nope,” I said. “A, too cold.”

You leaned down and gave me a lengthy kiss. “And B?”

“Actually that’s the only reason I can think of, is A.”

Your hands moved. “It’s not

that

cold,” you said. “We wouldn’t have to take

everything

off.”

“Ed—”

“I mean, we wouldn’t have to do a lot.”

I shrugged out of your arms, put the last shells in. “My test,” I said.

“OK, OK.”

“But thanks for taking me here. You’re right.”

“I told you it was perfect.”

“So for the party we have food—”

“Drink. Trevor said he’d do it. But it can’t just be champagne, it’s too word-I’m-not-allowed-to-say.”

“OK. And Trevor won’t be an asshole at the party?”

“Oh,” you said, “I guarantee he will. But not, you know, too much.”

“OK, so food, drink, music, lights. Everything but invitations and a guest list.”

“Everything but,” you said, with a tiny smirk. I threw a shell at you and then stood up to get it. I didn’t know why, not then. There was no reason to keep them, unremarkable nothings, even now they look like anything else.

But everything else is gone.

I mean

,

I love you

is gone, and your dance upon the stage, and all the perfection for the party. Even the party would have been gone, had we ever had it, the music back to Joan, the lights back in your attic, the food digested and the drinks thrown up, Lottie Carson driven home very politely and helped through her own sculpture garden to her front door late, late at night, tired from the lovely celebration, thankful and calling us

dear

. All gone, indelible but invisible, not quite everything but

everything but

. Mr. Nelson said it went on my permanent record, fifteen minutes late on a test day, but that’s gone too, along with my B- and the essay question I totally bluffed through, and gone is the reason I was late, how I ran to you and kissed your neck and pressed my hand against you, murmuring that it seemed like

everything but

felt pretty good to you. We didn’t do a lot, as you promised. We did a little, and the little is gone, those twenty-whatnot minutes scurried away wherever the actors go when the movie’s over and we’re blinking at the lights of the exit signs, wherever the old loves go when they move away with their asshole dads or just look elsewhere when I walk by in the halls. And the feeling, the real perfect of that afternoon, that you were thinking about me, that you’d remembered this garden and waited outside geometry to get me to skip class and see what you knew I’d love—that feeling’s gone forever too.