Why We Love Serial Killers (24 page)

Read Why We Love Serial Killers Online

Authors: Scott Bonn

In contrast to functionalism, the conflict perspective (or conflict theory) can be traced to the work of German philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818–1883), who believed that society is a dynamic entity that is constantly undergoing change driven by class conflict. Whereas functionalism perceives society as a complex system striving for equilibrium, the conflict perspective views it as constant competition. According to the conflict perspective, society is made up of individuals competing for limited resources such as money, real estate, or sexual partners. From a conflict perspective, competition over scarce resources is at the heart of all social relationships. Competition, rather than consensus, is the key characteristic of human relationships. Broader social structures and organizations such as religion and government reflect the competition for resources and the inherent inequality that competition entails. Thus, some people and organizations have more resources, including social power and influence, and use those resources to maintain their positions of dominance and control in society. Sociologists who operate from the conflict perspective study the distribution of resources, power, and inequality in society.

The third major sociological tradition, symbolic interactionism, is a theoretical approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between human beings and society. The basic premise of symbolic interactionism is that human actions and interactions are understandable only through the exchange of meaningful communication, language, or symbols. In this approach, humans are portrayed as acting, as opposed to being acted upon by larger social forces, as they are in functionalism and conflict theory.

86

As explained in

Symbolic Interaction: An Introduction to Social Psychology

, the main principles of symbolic interactionism are: 1) human beings act toward things on the basis of the meanings that things have for them; 2) all meanings arise out of social interaction; and 3) social action results from a fitting together of individual lines of action. According

to symbolic interactionism, the objective world has no reality for humans. Only subjectively defined objects and symbols have meaning for people. Meanings are not universal entities that are bestowed on humans and they are not learned objectively. Instead, social meanings can be altered through the creative capabilities of humans, and individuals may influence the many meanings that comprise their society. Therefore, according to symbolic interactionism, human society is subjectively defined in a particular context rather than being an objective, universal truth.

87

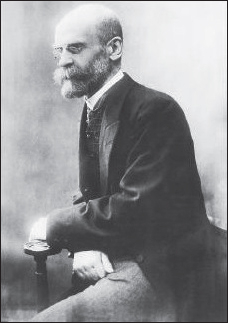

Emile Durkheim and Functionalism

The French social scientist Emile Durkheim (1858–1917), a leading developer and proponent of functionalism, is one of the most influential and respected sociologists in the history of the discipline. He is considered by many to be the founding father of modern sociology and, in many ways, criminology as well. Although Durkheim was not the first social scientist to advocate and employ the functionalist approach in his work, he is the figure most often associated with the theory. Durkheim began his academic career in the late 1800s, a time when sociology was not widely accepted in Europe or anywhere else as an independent scientific discipline. Durkheim devoted his life’s work to the advancement of sociology. In his first two major books originally published in the early 1890s,

The Division of Labor in Society

and

The Rules of Sociological Method

, Durkheim outlined what he perceived to be the distinctive theoretical problems and methodological strategies of sociological inquiry.

In his book on the rules of research methods, he identified the analysis of “social facts” as the unique subject matter for sociological inquiry. Social facts, according to Durkheim, are phenomena that are properties or patterns of society rather than of individual members of society. The rates of divorce, crime and suicide in a society and the nature of a society’s legal system are examples of social facts that Durkheim considered to be definitive of a society and to exist external to its individual members. Durkheim argued that social facts could only be explained sociologically—that is, in reference to other social facts. He said, “The determining cause of a social fact should be sought among the social facts preceding it and not among the states of the individual consciousness.”

88

French philosopher and social scientist Emile Durkheim.

Collective Consciousness and Social Solidarity

Emile Durkheim identified two concepts that are essential to an understanding of his functionalist theoretical perspective. These two important concepts are

collective consciousness

and

social solidarity

—both of which Durkheim used to support his conclusion that crime and deviance are not manifested in the actions of individuals but, rather, in the shared beliefs of the people in society. In

The Division of Labor in Society

, Durkheim defined collective consciousness as the totality of beliefs and sentiments that are common to the members of society.

89

In other words, collective consciousness represents a shared system of values and beliefs in which the boundaries of right and wrong, legal and illegal, are clearly defined. According to Durkheim, the collective consciousness is a powerful social force that existed before society’s current members were born and it will endure long after they are gone. Therefore, the collective consciousness of society has a life of its own and, most importantly, it provides the basis for social solidarity. According to Durkheim, solidarity refers to the ties that bind people to one another in society. In other words, solidarity is the integration or cohesion manifested by society in its individual members. The collective consciousness leads to social solidarity as certain common values and beliefs are diffused and integrated across society as a whole.

Durkheim applied his general functionalist principles to a specific form of deviance in his third major book, the groundbreaking

Suicide

, originally published in 1897. He deliberately focused on the seemingly individualistic phenomenon of suicide in order to demonstrate the power and singularity of sociological inquiry. What better or more dramatic phenomenon to build an argument for the importance of sociology as a scientific field than to look beyond the individual to society for

the causes of suicidal behavior? Using a tremendous amount of data from official records on suicides in different parts of Europe, Durkheim documented significant variations between countries in their rates of suicide. This evidence, Durkheim argued, shows that “each society has a definite aptitude for suicide” which is a social fact that is external to the individual members of a given society.

90

Additional analyses of these data convinced Durkheim that the suicide rate of a given society could not be explained by psychological abnormalities or other individual pathologies and that, “by elimination, it must necessarily depend upon social causes.”

91

It is important to understand that Durkheim was preoccupied with discovering and proving the effects of social change throughout his career. He sought to demonstrate/verify that certain conditions or characteristics of the social environment are the underlying causes of different patterns of suicide or other social facts. He believed, for example, that sudden, disruptive change in societal conditions such as a severe economic depression could lead to an increase in suicide. Durkheim identified four distinct environmental conditions that he believed to be responsible for various patterns of high suicide rates: egoism, altruism, anomie, and fatalism. In this chapter, we shall focus only on the best known of these four causes of suicide—anomie—because it relates directly to our discussion of serial homicide and helps to explain the actions of serial killers and their effect on society.

The Concept of Anomie

Durkheim explained

anomie

as a condition of deregulation and normative breakdown in society.

92

Stated differently, anomie is a condition where social norms or expectations of behavior are confused, unclear, or simply not present. Anomie occurs in society when the rules on how people ought to behave with each other crumble and, as a result, people do not know what to expect from one another. Durkheim believed that individuals cannot find their place or function properly in society without clear rules to help guide them. In a state of anomie, the members of society no longer have clear social norms to regulate or constrain their goals and desires. A society characterized by anomie fails to exercise adequate control over the actions and behaviors of its individual members. The state of norm confusion or normlessness that occurs in a society characterized by anomie can lead its individual members to engage in deviant behavior such as violence and suicide.

As explained by Dr. James Orcutt in his fine book

Analyzing Deviance

, Durkheim believed that the condition of anomie could explain at least three kinds of suicidal phenomena.

93

First, using historical data on suicide patterns in Europe, Durkheim determined that sharp increases or decreases in the economic wellbeing of a society were associated with an increasing rate of suicide. He further found that suicide rates were lowest during times of economic stability and highest during times of economic instability. Durkheim reasoned that economic crises disrupted society’s regulatory influence on the material desires of its members. Economic booms or depressions undercut the predictable material goals from which individuals would ordinarily derive satisfaction. Second, Durkheim presented evidence that “one sphere of social life—the sphere of trade and industry—is actually in a chronic state” of anomie.

94

In commercial segments of society, where far-reaching, aggressive economic goals are continually sought and greed is aroused in people without their knowing where to find an outlet, a lack of moral restraint over material desires becomes a constant plague of the social environment. Durkheim explained high rates of suicide among business people as a result of this chronic state of anomie. Finally, Durkheim analyzed how inadequate regulation of sexual desires could also produce high rates of anomic suicide among certain social groups. Single males, in particular, are in social circumstances where their unrestrained pursuit of physical pleasure is likely to lead to disillusionment and suicide, according to Durkheim. Marriage functions to regulate sexual desire and married males typically have lower rates of suicide than unmarried males. Durkheim documented these patterns and considered them to be important social facts. The concept of anomie was thus used by Durkheim to explain a variety of social facts as they relate to suicide, including occupation, employment status, and marital status.

It is also important to recognize that Durkheim’s conceptualization of anomie is based on a general assumption about the biological nature of individual human beings. He believed that the human “capacity for feeling is in itself an insatiable and bottomless abyss.”

95

From Durkheim’s viewpoint, individual happiness and well being depend on the ability of society to impose external limits on the potentially limitless passions and appetites that characterize human nature in general. Under the condition of anomie, however, society is unable to exert its regulatory and disciplining influences. Human desires are left unchecked and unbounded—that is, the individual aspires to everything and is satisfied

with nothing. Out of disillusionment and despair with the pursuit of limitless goals, many individuals in an anomic society take their own lives, according to Durkheim. Therefore, high rates of anomic suicide are the product of the environmental condition of anomie. By extension, high rates of other deviant or criminal acts such as alcoholism, rape, or murder may also be attributed to the existence of anomie in society.

Durkheim’s work has been the subject of extensive discussion and debate over the years, as noted by Dr. James Orcutt in

Analyzing Deviance

. Nonetheless, Durkheim’s study of suicide has endured as a classic example of the functionalist sociological approach to theory and research on deviance. Some social scientists have questioned the sociological purity of Durkheim’s analysis by pointing out that certain psychological rather than sociological assumptions about the limitless nature of human desires can be found in his writings on suicide. However, Durkheim generally treated psychological human qualities or potentials as constants rather than as variables in his research. In other words, he viewed human nature as fundamentally the same in its essential qualities among all people. According to Durkheim, variations in suicide rates cannot be explained by psychological constants that exist among all people but only by variations in the social environment that lies outside of individuals and exerts external influences upon them. Following the clear directions and path laid down by Durkheim, the functionalist tradition in sociology has continued to focus its search for the causes of crime and deviant behavior on large-scale variations in the environmental features of society.