Wicca (9 page)

*

One of these that usually isn’t stated is the most obvious: people like to look at naked bodies. Some unscrupulous persons form covens with the sole purpose of practicing social nudity. Such groups, it is readily apparent, aren’t promoting the aims of Wicca: union of the Goddess and God and reverence for nature. I hasten to add that the majority of covens that practice ritual nudity aren’t of this type.

*

I realize that this is a heretical statement. Many Wiccans become quite angry when I suggest this. Such a reaction is the product of traditional Wiccan training. I feel, however, that wearing clean street clothing during ritual is no more absurd than is doning the ubiquitous, hot, and uncomfortable robes that so many Wiccans seem to love. To each their own.

7

The Magic Circle and the Altar

THE CIRCLE, MAGIC

circle, or sphere is a well-defined though nonphysical temple. In much of Wicca today, rituals and magical workings take place within such a construction of personal power.

The magic circle is of ancient origin. Forms of it were used in old Babylonian magic. Ceremonial magicians of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance also utilized them, as did various American Indian tribes, though not, perhaps, for the same reasons.

There are two main types of magic circles. Those used by ceremonial magicians of yesterday (and today) are designed to protect the magician from the forces which he or she raises. In Wicca, the circle is used to create a sacred space in which humans meet with the Goddess and God.

In pre-Christian Europe, most pagan religious festivals occurred outdoors. These were celebrations of the sun, moon, the stars, and of the earth’s fertility. The standing stones, stone circles, sacred groves, and revered springs of Europe are remnants of those ancient days.

The pagan rites went underground when they were outlawed by the newly powerful Church. No longer did meadows know the sounds of voices chanting the old names of the sun gods, and the moon hung unadored in the nighttime skies.

The pagans grew secretive about their rites. Some practiced them outside only under the cover of darkness. Others brought them indoors.

Wicca has, unfortunately, inherited this last practice. Among many Wiccans, outdoor ritual is a novelty, a pleasant break from stuffy housebound rites. I call this syndrome “living room Wicca.” Though most Wiccans practice their religion indoors, it’s ideal to run the rites outside beneath the sun and moon, in wild and lonely places far from the haunts of humans.

Such Wiccan rites are difficult to perform today. Traditional Wiccan rituals are complex and usually require a large number of tools. Privacy is also hard to find, and fear of merely being seen is another. Why this fear?

There are otherwise responsible, intelligent adults who would rather see us dead than practicing our religion. Such “Christians”

*

are few but they certainly do exist, and even today Wiccans are exposed to psychological harassment and physical violence at the hands of those who misunderstand their religion.

Don’t let this scare you off. Rituals can be done outdoors, if they’re modified so as to attract a minimum of attention. Wearing a black, hooded robe, stirring a cauldron, and flashing knives through the air in a public park isn’t the best way to avoid undue notice.

Street clothing is advisable in the case of outdoor rituals in areas where you may be seen. Tools can be used, but remember that they’re accessories, not necessities. Leave them at home if you feel that they’ll become problems.

On a 1987 trip to Maui, I rose at dawn and walked to the beach. The sun was just rising behind Haleakala, tinting the ocean with pinks and reds. I wandered along the coral sand to a place where the warm water crashed against lava rocks.

There I set up a small stone in the sand in honor of the ancient Hawaiian deities. Sitting before it, I opened myself to the presence of the

akua

(gods and goddesses) around me.Afterward I walked into the ocean and threw a plumeria lei onto the water, offering it to Hina, Pélé, Laka, Kane, Lono, Kanaloa, and all their kin.

†

I used no lengthy speeches and brandished no tools in the air. Still, the deities were there, all around, as the waves splashed against my legs and the sunrise broke fully over the ancient volcano, touching the sea with emerald light.

Outdoor rituals such as this can be a thousand times more effective

because they are outdoors,

not in a room filled with steel and plastic and the trappings of our technological age.

When these aren’t possible (weather is certainly a factor),Wiccans transform their living rooms and bedrooms into places of power. They do this by creating sacred space, a magical environment in which the deities are welcomed and celebrated, and in which Wiccans become newly aware of the aspects of the God and Goddess within.Magic may also be practiced there. This sacred space is the magic circle.

It is practically a prerequisite for indoor workings. The circle defines the ritual area, holds in personal power, shuts out distracting energies— in essence, it creates the proper atmosphere for the rites. Standing within a magic circle, looking at the candles shining on the altar, smelling the incense and chanting ancient names is a wonderfully evocative experience. When properly formed and visualized, the magic circle performs its function of bringing us closer to the Goddess and God.

The circle is constructed with personal power that is felt (and visualized) as streaming from the body, through the magic knife, (athame) and out into the air. When completed, the circle is a sphere of energy that encompasses the entire working area. The word “circle” is a misnomer; a

sphere

of energy is actually created. The circle simply marks the ring where the sphere touches the earth (or floor) and continues on through it to form the other half.

Some kind of marking is often placed on the ground to show where the circle bisects the earth. This might be a cord lain in a roughly circular shape, a lightly drawn circle of chalk, or objects situated to show its outlines. These include flowers (ideal for spring and summer rites); pine boughs (winter festivals), stones or shells; quartz crystals, even tarot cards. Use objects that spark your imagination and are in tune with the ritual. (See chapter 13, Ritual Design, for more information regarding the magic circle.)

The circle is usually nine feet in diameter,

*

though any comfortable size is fine. The cardinal points are often marked with lit candles, or the ritual tools assigned to each point.

The pentacle, a bowl of salt, or earth may be placed to the north. This is the realm of earth, the stabilizing, fertile, and nourishing element that is the foundation of the other three.

The censer with smoldering incense is assigned to the east, the home of the intellectual element, air. Fresh flowers or stick incense can also be used. Air is the element of the mind, of communication, movement, divination, and ascetic spirituality.

To the south, a candle often represents fire, the element of transformation, of passion and change, success, health, and strength.An oil lamp or piece of lava rock may be used as well.

A cup or bowl of water can be placed in the west of the circle to represent water, the last of the four elements. water is the realm of the emotions, of the psychic mind, love, healing, beauty, and emotional spirituality.

Then again, these four objects may be placed on the altar, their positions corresponding to the directions and their elemental attributes.

Once the circle has been formed around the working space, rituals begin. During magical workings the air within the circle can grow uncomfortably hot and close—it will truly feel different from the outside world, charged with energy and alive with power.

The circle is a product of energy, a palpable construction that can be sensed and felt with experience. It isn’t just a ring of flowers or a cord but a solid, viable barrier.

In Wiccan thought the circle represents the Goddess, the spiritual aspects of nature, fertility, infinity, and eternity. It also symbolizes the earth itself.

The altar, bearing the tools, stands in the center of the circle. It can be made of any substance, though wood is preferred. Oak is especially recommended for its power and strength, as is willow that is sacred to the Goddess.

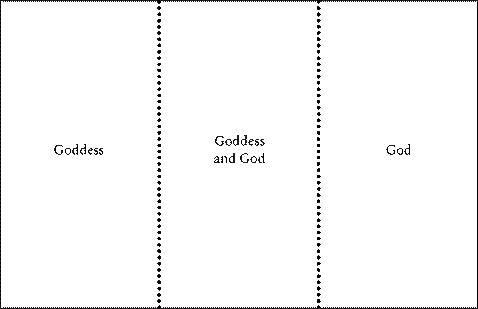

Symbolic divine areas of the altar

The Wicca don’t believe that the Goddess and God inhabit the altar itself. It is a place of power and magic, but it isn’t sacrosanct. Though the altar is usually set up and dismantled for each magical ritual, some Wiccans have permanent home altars as well. Your shrine can grow into such an altar.

The altar is sometimes round, to represent the Goddess and spirituality, though it may also be square, symbolic of the elements. It may be nothing more than an area of ground, a cardboard box covered with cloth, two cinder blocks with a board lying on top, a coffee table, an old sawed-off tree stump in the wild, or a large, flat rock. During outdoor rituals, a fire may substitute for the altar. Stick incense may be used to outline the circle. The tools used are the powers of the mind.

The Wiccan tools are usually arranged upon the altar in a pleasing pattern. Generally, the altar is set in the center of the circle facing north. North is a direction of power. It is associated with the earth, and because this is our home we may feel more comfortable with this alignment. Then too, some Wiccans place their altars facing east, where the sun and moon rise.

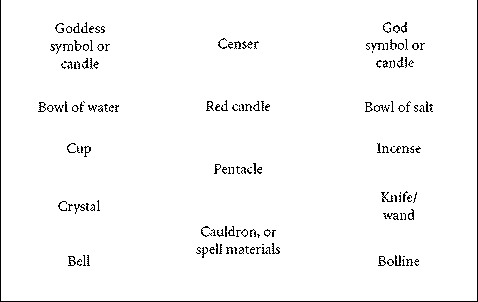

The left half of the altar is usually dedicated to the Goddess. Tools sacred to her are placed there: the cup, the pentacle, bell, crystal, and cauldron.An image of the Goddess may also stand there, and a broom might be laid against the left side of the altar.

*

If you can’t find an appropriate Goddess image (or, simply, if you don’t desire one), a green, silver, or white candle can be substituted. The cauldron is also sometimes placed on the floor to the left side of the altar if it is too large to fit on top.

To the right side, the emphasis is on the God. A red, yellow, or gold candle, or an appropriate figure, is usually placed there, as are the censer, wand, athame (magic knife), and white-handled knife.

Flowers may be set in the middle, perhaps in a vase or small cauldron. Then too, the censer is often centrally situated so that its smoke is offered up to both the Goddess and the God, and the pentacle might be placed before the censer.

Some Wiccans follow a more primitive, nature-oriented altar plan. To represent the Goddess, a round stone (pierced with a hole if available), a corn dolly, or a seashell work well. Pine cones, tapered stones, and acorns can be used to represent the God. Use your imagination in setting up the altar.

If you’re working magic in the circle, all necessary items should be within it before you begin, either on the altar or beneath it. Never forget to have matches handy, and a small bowl to hold the used ones (it’s impolite to throw them into the censer or cauldron).

Though we may setup images of the Goddess and God,we’re not idol worshippers. We don’t believe that a given statue or pile of rocks actually is the deity represented. And although we reverence nature, we don’t worship trees or birds or stones. We simply delight in seeing them as manifestations of the universal creative forces—the Goddess and God.

Suggested altar layout

The altar and the magic circle in which it stands is a personal construction and it should be pleasing to you.My first Wiccan teacher laid out elaborate altars attuned with the occasion—if we couldn’t practice outdoors. For one full moon rite she draped the altar with white satin, placed white candles in crystal holders, added a silver chalice, white roses, and snowy-leafed dusty miller. An incense composed of white roses, sandalwood, and gardenias drifted through the air. The glowing altar suffused the room with lunar energies. Our ritual that night was one to remember.

May yours be the same.

*

I put quotes around this word for obvious reasons: such violent, crazed individuals certainly aren’t Christians. Even Fundamentalists usually limit their activities to preaching and picketing—not violence, fire-bombing, and beatings.