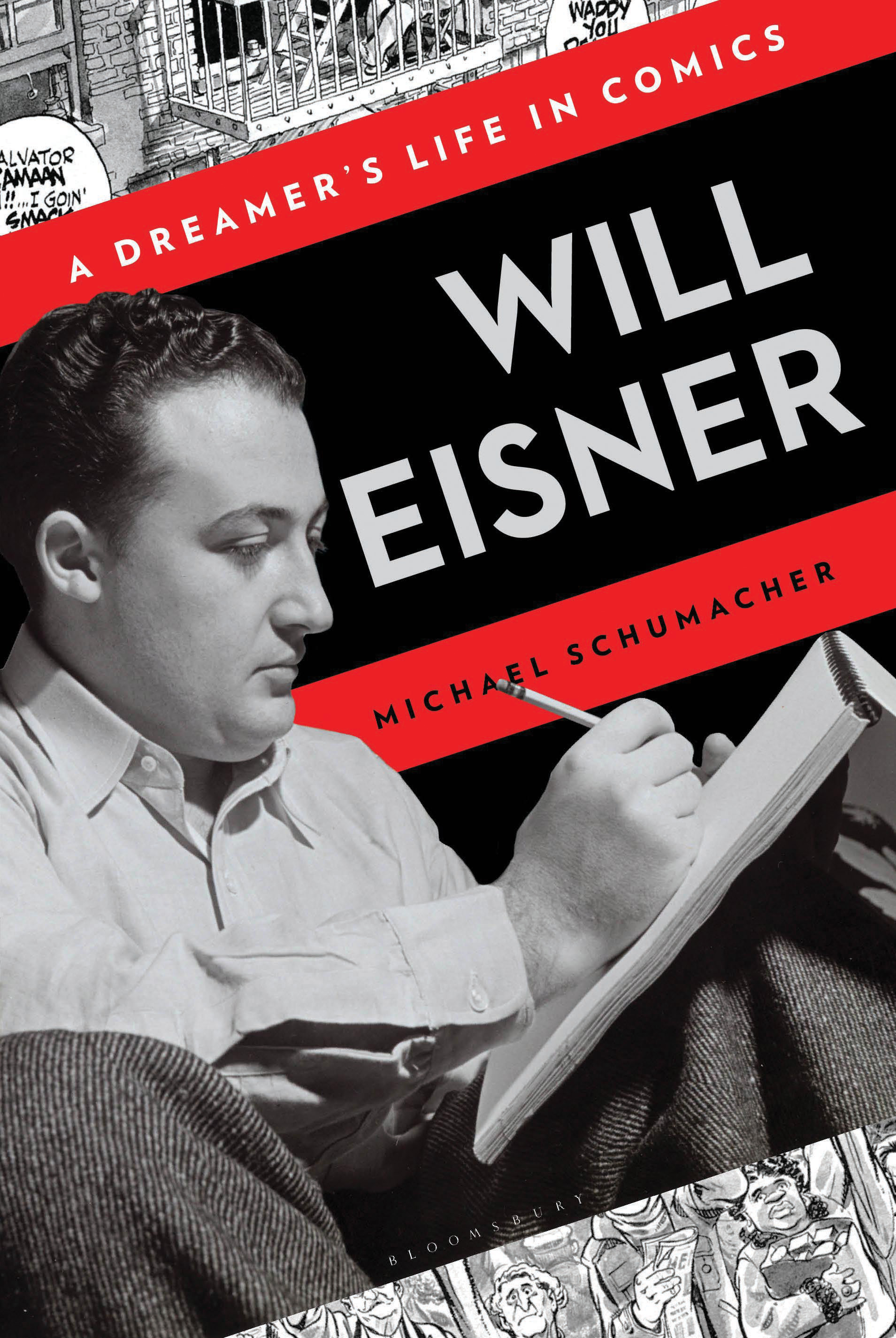

Will Eisner

Authors: Michael Schumacher

W I L L E I S N E R

A Dreamer’s Life in Comics

M i c h a e l S c h u m a c h e r

T o I v y a n d D y l a n

w h o s e d r e a m s I c a n ’ t r e m e m b e r o r i m a g i n e

I wasn’t aware that I was making a revolution. I knew what I was

doing was different because I

meant

it to be different, and I was talking

to a totally different reader.

—Will Eisner

We used to feel very much like a Mama Rabbit and a Daddy Rabbit,

who were running around, being chased by a bunch of dogs. They

dove into a hole and the Mama Rabbit is quivering. She’s saying,

“Oh, this is terrible. We’re doomed.” The Daddy Rabbit says, “No,

don’t worry about it. We’ll stay here, and in a half an hour, we’ll

outnumber them.” I always think of that when people ask me how

I felt about all those years of so-called struggle.

—Will Eisner

C O N T E N T S

Chapter 1

The Depression’s Lessons

Chapter 2

A Business for Thirty Bucks

Chapter 3

Supermen in a World of Mortals

Chapter 4

A Spirit for All Ages

Chapter 5

A Private Named Joe Dope

Chapter 6

Flight

Chapter 7

Ann

Chapter 8

Out of the Mainstream

Chapter 9

Back in the Game

Chapter 10

Resurrection

Chapter 11

A Contract with God

Chapter 12

Outer Space, the City—No Limits

Chapter 13

A Life Force

Chapter 14

Winners and Losers

Chapter 15

The Heart of the Matter

Chapter 16

Polemics

chapter one

T H E D E P R E S S I O N ’ S L E S S O N S

I carry with me a cargo of memories, some painful and some pleasant,

which have remained locked in the hold of my mind. I have an ancient

mariner’s need to share my accumulation of experience and observations.

Call me, if you will, a graphic witness reporting on life, death,

heartbreak and the never-ending struggle to prevail …

or at least to survive.

W

ill Eisner boasted that he could draw the New York City of his childhood from memory, that he didn’t have to consult old photographs or conduct research to conjure up images of towering tenement buildings with their wrought-iron fire escapes and broken front stoops, of clothes hanging on lines cast between buildings, of fire hydrants and subway grates, of endless rows of grimy windows, of kids playing stickball in the street and their parents engaged in the mighty struggle of stretching a few last dollars from Tuesday to Friday, hollering their frustrations at one another or, if the moment was right and the shades were drawn, slipping into tenderness offering reassurance, if not promise. To the New Yorker growing up in Depression-era Bronx or Brooklyn, as Eisner did, the neighborhoods, packed tight with immigrants and buildings and shifty politics, were places to survive until hope began to make sense. Eisner’s graphic novels caught all this and more, often in tenement buildings on the fictitious Dropsie Avenue, where Eisner’s memories gathered and, in the solitude of a drawing board, took flight.

“The city, to me, is a big theater,” he once said. “It’s a never-ending source of story, largely because there’s a concentration of human beings who are impacting on each other. And each human carries with him, or her, a whole story. It’s a struggle for existence.”

Eisner was always the outsider. His family moved frequently, usually as the result of his father’s inability to pay rent and make ends meet, so as the perpetual new kid on the block, he was continually the observer, again and again learning the lay of the land, guarding his younger brother and sister, dealing with these lower-middle-class neighborhoods’ anti-Semitism, finding a way to fit in—surviving. And, too soon, at an age when other boys were trying out the fit of adolescence, he became the unofficial head of the household, the provider. His childhood was over and his city shrank.

Born on March 6, 1886, Shmuel (Samuel) Eisner, Will Eisner’s father, was an old world artist and intellectual who learned, during the bleak days of the Depression, that neither art nor intellectualism could buy you a half a loaf of bread or a few eggs at the corner store. Sam Eisner’s perfect world was Viennese café society: fine art painting, intelligent conversation, literature, friends, and endless cups of strong coffee. And, yes, watching his children grow into healthy, happy adults. Life was enrichment of the mind, and joy was finding a creative way to express that enrichment.

His real world bore little resemblance to this. He was born in Austria, in Kollmei, a village not far from Vienna. His father, a laborer—“a kerosene miner or something like that,” as Will Eisner would recall—had all he could handle in feeding his wife and eleven children.

Although he never formally studied art, Sam was a natural painter, gifted with backgrounds and landscapes, enough so that when he moved to Vienna as a teenager, he was able to find a job as a muralist’s apprentice. Wealthy patrons hired him to paint scenes on the walls of their homes, or more often Sam would find himself decorating the walls and ceilings of Vienna’s Roman Catholic churches. This irony, of a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old Jewish boy painting blue skies and fluffy clouds and rosy-faced singing cherubim in a Catholic church, would amuse his son for his entire adult life.

One by one, Sam’s brothers and sisters moved away, some to other cities in Europe, others overseas to America, where they established residence, found work, and sent for other siblings. Rather than face enlistment in the army, Sam left Vienna for the United States, arriving in New York just before the outbreak of World War I. If he envisioned America as a land brimming with opportunity and potential wealth, that notion was quickly put to rest. Sam knew how to speak German and Yiddish, but not English, and he learned early on that job hunting was going to be challenging: there was very little demand for alfresco painters in New York City. He eventually landed a job as a background painter for stages in Yiddish and vaudeville theaters—a far cry from the kind of art he aspired to create and earning him barely enough to get by. Like many immigrants, he attended night school to learn English, but it was tedious and the language came slowly to him.

*

Fortunately, though, he was gregarious and charming by nature, and he made friends easily.

Perhaps it was this charm, and particularly his ability to tell a good story, that attracted Fannie Ingber to him, for it is otherwise difficult to imagine what brought together this most unlikely couple. Fannie, a Romanian, had been born on April 25, 1891, on a ship bound for America. Her father, Isaac, seventy at the time of her birth, had been married to Fannie’s mother’s older sister, and when she died of influenza, he’d returned to his homeland for another wife. Fannie’s mother, a sickly woman, died on Fannie’s tenth birthday, and Isaac Ingber died later that same year, leaving Fannie in the custody of an older stepsister, Rose, who treated her more like a slave than family. Besides being overloaded with household chores, Fannie helped Rose do piecework for a garment factory and looked after her younger brother and sister. She found very little time or use for enjoying friends, hobbies, or the big city around her. When she grew older, she dated a few young men, but none of them met with the approval of her stepsister, who in all likelihood was more concerned about losing a servant than gaining a brother-in-law.

Fannie dreamed of saving enough money to open her own business, preferably a bakery, but by the time she had met, courted, and married Sam Eisner, she was hard-bitten and realistic enough to know that dreams were meant for people with better backgrounds than hers. She had worked while others had attended school; she knew English, but she couldn’t read or write it—a fact that she went to great lengths to hide from her children. Factory work, at which she had excelled, had prepared her for a life of repetition. To Fannie, life was something to endure.

According to Will Eisner, his parents were distantly related, maybe second or third cousins, and they had been introduced by family. They had absolutely nothing in common, other than they were single, had ties to Europe, had a few nearby relatives they weren’t especially close to, and possessed limited marketable job skills. They did have each other, but, as Will Eisner showed in his autobiographical work,

To the Heart of the Storm

, that offered little cause for celebration. Fannie wept when she accepted Sam Eisner’s marriage proposal. The only thing that frightened her more than the prospect of marriage was the possibility of growing old alone.

William Erwin Eisner, the first of his parents’ three children, was born in New York City on March 6, 1917, the same month and day as his father. As time would show, he was an almost perfect combination of his parents’ strongest traits: artistic dreamer and steely realist. A brother, Julian, followed four years later, on February 3, 1921, and a sister, Rhoda, was born on November 2, 1929.

Called Billy or Willie by his parents, Eisner claimed that, as a boy, he never fully realized how impoverished his family was. His father was always working at some type of job, normally a low-paying one, and his family lived in modest but not run-down apartments. If his parents were ill suited for each other, at least it wasn’t open warfare all the time. Fannie Eisner would berate her husband, often in front of the children, for his failure to earn a decent living and for the way he always seemed to be borrowing money or relying on other assistance from his older brother Simon, but Sam seemed willing to shrug off the barbs rather than allow them to escalate into serious altercations.

Billy Eisner, at age one. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State University

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Billy saw enough hardship in his friends’ families to lead him to believe that tensions over money were normal. When the sniping began, Billy would turn his attention to a book, close himself off in his room, or head outside, to a cacophony of noise that obliterated the angry sounds within his apartment, unaware that someday his graphic novels would bear the fruits of this distraction.

Fannie Eisner suffered from debilitating headaches, which she attributed to her difficult life. Sam, she claimed, was killing her with his job problems. She would have preferred that he just take a job painting houses, a practical enough solution to their money woes. But he would hear none of it. He was smarter than the common laborer, and he would find a way of using his talents to succeed.

Unfortunately, even though his labor wasn’t common, it was sporadic, and success eluded Sam Eisner. Opportunities for scene painting dried up as time went on, with vaudeville slowing down and movies picking up in popularity. At Fannie’s urging, Sam left that work for a more promising—and far less interesting—job painting finish on metal beds, making the beds look as if they had been constructed of mahogany or walnut. But the benzine and turpentine used in the process made him ill, and after consulting with a doctor, he had to quit. Then he tried his hand at opening a secondhand furniture store, but it lasted barely a year. Sam reasoned that new furniture was being produced and sold so cheaply that he couldn’t compete. After the furniture store debacle, Sam, bankrolled by his brother Simon, opened a fur-coat-manufacturing factory. This, too, spiraled to disaster, and after four years of lousy sales, largely because Sam couldn’t spot the trends in the business, Simon and a couple of other investors pulled the plug on the venture.

For the Eisner family, these different jobs meant a lot of moving around—or at least that’s the story Sam preferred to tell them. More likely it was a matter of moving before the family faced eviction. It was getting tougher and tougher to make rent, and the moves were to cheaper places. The bed-painting job found the Eisners relocating to New Jersey, only to head to Brooklyn for the furniture store. Then it was off to the Bronx. Staying hopeful wasn’t easy for the normally upbeat Sam Eisner, not when he was being badgered by an increasingly impatient wife and when he saw the difficulties the moves placed on his kids, particularly his oldest son.

Mother and son, in an undated photo. (Will Eisner Collection, the Ohio State

University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Billy Eisner, age three, with his parents, Sam and Fannie Eisner. (Will Eisner Collection,

the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

Each new neighborhood meant establishing a presence, making friends, fending off threats, and meeting new schoolmates and teachers. The neighborhoods were occupied by Irish and Italians with appalling anti-Semitic attitudes, and young Billy Eisner, not the most patient person to begin with, wasn’t inclined to take a lot of crap. He’d use his fists whenever he felt it necessary, despite his father’s counsel that brainpower would beat brutishness. Sam Eisner had faced such anti-Semitism in Europe, and for him, the United States was just more of the same. Billy would come home with cuts and scrapes and black eyes, still seething in anger from the latest string of slurs flung in his face, only to have his father advise him that bigotry, sadly enough, was an element of living in a city where different kinds of people gathered. At one time, Sam explained, the Italians and Irish picking on Billy had been victimized by prejudice themselves.