Winger (2 page)

Authors: Andrew Smith

Besides wearing ties and uniforms, all students were required to play sports at PM. I kind of fell into rugby because running track was so boring, and rugby’s a sport that even small guys can play—if you’re fast enough and don’t care about getting hit once in a while.

So I figured I could always outrun Chas if he ever went over the edge and came after me. But even now, as I write this, I can still remember the feeling of sitting on the bottom bunk, there in our

quiet room, just staring in dread at the door, waiting for my roommate to show up for first-semester check-in on that first Sunday morning in September.

All I had to do was make it through the first semester of eleventh grade without getting into any more trouble, and I’d get a chance to file my appeal to move back into my room with Seanie and JP in the boys’ dorm. But staying out of trouble, like not getting killed while living with Chas Becker, was going to be a full-time job, and I knew that before I even set eyes on him.

NO ONE HAD TO KNOCK

in O-Hall.

The knobless doors couldn’t be locked, anyway.

That’s the biggest part of the reason why my day started off upside down in a toilet.

So when I heard the door creak inward, it felt like all my guts knotted down to the size of a grape.

It was only Mr. Farrow, O-Hall’s resident counselor, pushing his mousy face into the room, scanning the surroundings through thick wire glasses and looking disappointedly at my unopened suitcase, the duffel bag full of rugby gear stuffed and leaning beside it, a barrier in front of me, while I slumped down in the shadows of the lower bunk like I was hiding in a foxhole, preparing for Chas Becker’s entrance.

“Ryan Dean,” he said, “you’ll have time to unpack your things before picking up your schedule, but I’m afraid you’ll need to hurry.”

I looked past Farrow’s head, into the dark hallway, to see if he was alone.

I was still missing one shoe.

“I can do it this afternoon, Mr. Farrow,” I said. “Or maybe after dinner.”

I leaned forward and put my hands on my suitcase. “Should I go to the registrar?”

“Not yet.” Mr. Farrow looked at a folder of schedules in his hands. “Your appointment is at one fifteen. You have time.”

A shadow moved behind him.

“Excuse me, Mr. Farrow.”

And there was Chas Becker, pushing the door wide and squeezing

past Farrow as he hefted two canvas duffels that looked like the things a coroner would use to cart away bodies, and dropped them with a

thud!

in the middle of the floor.

Then Chas noticed me, and I could see the confused astonishment on his face.

“I’m rooming with

Winger

?” He turned to look at Farrow, like he didn’t know if he was in the right place. Then he leered at me again. “How’d Winger end up in O-Hall?”

I didn’t know if I should answer. And I didn’t know if Chas even knew my actual name, because, like a lot of the guys on the team, he just called me Winger or Eleven (which was the number on my jersey), or the couple times when I’d dorked a kick, he called me Chicken Wing, or something worse that included the French word for “shower.”

I glanced at Farrow, who shrugged like he was waiting for me to say something. Oh, and besides the sports, no cell phones, and the neckties and uniforms, PM had a very strict ethics policy about telling the truth, especially in front of officers of the Truth Police like Mr. Farrow.

“I stole a cell phone.” I swallowed. “From a teacher.”

“Winger’s a boost?” Chas smiled. “How cool is that? Or is it dorky? I don’t get it.”

I felt embarrassed. I looked at my hands resting on my suitcase.

And then Chas, all six-foot-four inches and Mohawk-stripe of hair

pointing him forward, stepped toward the bed, loomed over me like some giant animated tree, and said, “But you’re sitting on my bed, Winger. Don’t ever sit on my bed. You get tops.”

“Okay.”

I wasn’t about to argue the Pine Mountain first-come-first-served tradition. Anyway, I thought he was going to hit me, so I was happy that Mr. Farrow was watching our heartwarming get-acquainted moment. Even though I’d always liked school, I suddenly realized how shitty this particular Sunday-before-the-school-year-begins was turning out after the simple addition of one Chas Becker. That, and the whole head-in-a-toilet thing.

And Mr. Farrow cleared his throat, mousylike, saying, “You’re going to need to reinvent the haircut, Chas.”

Nothing that bordered on the undisciplined or unorthodox was tolerated at PM. Not even facial hair, not that I had anything to worry about as far as that rule was concerned. I’d seen some girls at PM who came closer to getting into trouble over that rule than me. The only thing I’d ever shaved was maybe a few points off a Calculus test so my friends wouldn’t hate me if I set the curve too high.

“I’ll shave it off after schedules,” Chas said.

“You’ll need to do it before,” Farrow answered. He explained, “You know that ID pictures are today, and you’re not going in looking like that.”

I waited until Chas backed up a step, and then I stood up, hitting my head squarely on the metal frame beneath my new sleeping spot.

And as I rubbed my scalp I thought Chas was probably just waiting for Farrow to leave so he could reassign me to the floor.

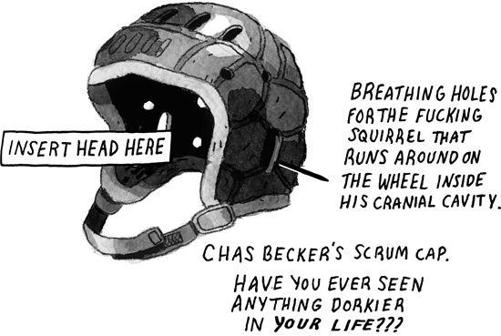

“You need to wear a scrum cap when you go to bed, too, Winger?” Scrum caps are things that some players wear to protect their heads in rugby. But wings don’t wear them, and all they really are good for is keeping your ears from getting torn off, so second-row guys like Chas

had

to wear them. In fact, I clearly saw one on top of his kit bag when he came in and I felt like—

really

felt like—giving him a clever comeback so Farrow could see the new, eleventh-grade version of me, but I couldn’t think of anything witty because my head hurt so bad.

I fucking hated Chas Becker.

There were chairs at each of the desks in the room, but I knew better than to pull one out, because Chas would just say that was his too. And as I fumbled with climbing up onto the top bunk, wondering

how I was ever going to get in and out of bed if I needed to pee in the middle of the night, already mentally rigging the Ryan Dean West Emergency Gatorade Bottle Nighttime Urinal I would have to invent, Farrow slipped backward out the door and pulled it shut behind him.

So it was me and Chas.

Pure joy.

Bonding time.

And I couldn’t help but wonder how much blood could actually be contained by the 160-pound sack of skin I walked around in.

Well, to be honest, it’s 142.

Yeah . . . I am a skinny-ass loser.

And I’d had a talk with my very best friend, Annie, just that morning when we showed up at school. Annie Altman was at Pine Mountain because she

chose

to enroll at the school. Go figure.

Annie Altman was going into eleventh grade too, which meant she was two full years older than me, so, most people would think there couldn’t possibly be anything between us beyond a noticeable degree of friendship, even if I did think she was smoking hot in an alluring and mature, “naughty babysitter” kind of way. I was convinced, though, that as far as Annie was concerned, I was more or less a substitute for a favored pet while she had to be here at PM, probably a red-eared turtle or something. At least she usually got to go home on weekends and see the pets she really loved.

I had hoped that she’d get over it, but there’s no balancing act

between fourteen-year-old boys and girls who are sixteen, even if I did grow taller over the summer, even if I didn’t sound or look like such a little kid anymore.

Even if Annie knew everything in the world about me.

Well, I didn’t tell her about the toilet thing.

Anyway, Annie told me that this was going to be my make-it-or-break-it year, and that I was going to have to suck it up if I was going to survive in O-Hall, which is about the same as a state pen as far as we were concerned.

It kind of made me feel all flustered and choked up when she told me that I might have to take a few lumps in order to gain the respect of the other inmates so they’d learn right away not to mess with Ryan Dean West.

She said she’d learned that particular strategy by watching a documentary about guys who get killed in jail.

So now that Chas and I were alone, I closed my eyes and tried to relax, wondering if I was taking my final breaths or taking the first steps toward standing up to Chas Becker and becoming someone new.

Or something.

There weren’t any lights on in our room. That was bad, I thought. People like to do terrible things to other people when the lights are out, even if it’s daytime.

In the unvoiced and universal language of psychopaths, a flipped-down light switch is like one of those symbol-sign thingies that would

show a silhouette stick figure strangling the skinny silhouette stick figure of a fourteen-year-old.

I could see the swath of Chas’s Mohawk pointing at me, and the whites of his eyes looking straight across at me, where I sat on the bunk bed.

Chas began unpacking, stuffing his folded clothes into the cubbies stacked like a ladder along one side of our shared closet.

“You got any money?” he asked.

And I thought,

God, he’s already going to start with the extortion

. I tried to remember what Annie told me, but the toughest, most stand-up-for-yourself thing that wasn’t in Latin I could think of was “Why?”

Chas folded his empty bags and kicked them under the bed. He turned around, and I could practically feel him breathing on me. He put both of his hands on the edge of my bed, and at that moment I felt like a parakeet—but a tough, stand-up-for-yourself variety of parakeet—in a stare-down with a saltwater crocodile.

“After lights-out, a couple of the guys are going to sneak in here for a poker game. That’s why. We always play poker here on Sundays. Twenty-dollar buy-in. Do you know how to play poker?”

“Count me in.”

I don’t know if the choking or unconsciousness urge was stronger at that point, but I survived my first private, witness-free encounter with the one guy who I was convinced would end up trying his hardest to thoroughly ruin my life just before killing me sometime during my eleventh-grade year at Pine Mountain.

AFTER CHAS TRIMMED HIS MOHAWK

down to a buzz cut, we put on our shirts and ties and went to the registrar to get our schedules and ID photos taken—not that we actually walked there together.

I saw my former roommates, Seanie and JP, waiting in line for pictures, and it made me feel good to see my old friends, but sad, too, because I missed rooming with them. We all three shared a room for our first two years at PM.

In the regular boys’ dorm, the rooms were big and comfortable and usually had three or four guys per room, not like O-Hall, where the rooms were like tiny cells with those dreaded metal bunk beds.

Seanie and JP played rugby too. We hung out and got along because they weren’t forwards either. Seanie played scrum half, even though he was really tall and skinny, but he had a wicked pass and flawless hands; and JP played fullback, which is the position usually given to the all-around fittest, most-confident guy on the team, and with the highest tolerance for pain. This year, they’d both be moving up to the varsity team since about half the starters from last year had graduated.