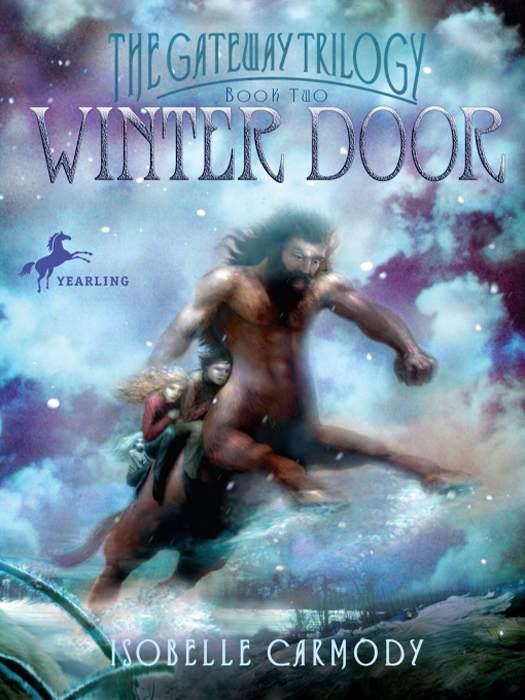

Winter Door

Authors: Isobelle Carmody

Contents

Join Rage, Billy Thunder, and their...

Other Yearling Books You Will Enjoy

For my nephew John,

For my nephew John,

brave enough to be gentle

If human lives be, for their very brevity, sweet, then beast lives are sweeter still. But sweetest of all is the Mayfly day. That life, between sunrise and set, is pure ecstasy.

For more than forty years, Yearling has been the leading name in classic and award-winning literature for young readers.

Yearling books feature children’s favorite authors and characters, providing dynamic stories of adventure, humor, history, mystery, and fantasy.

Trust Yearling paperbacks to entertain, inspire, and promote the love of reading in all children.

There was a rattle of hailstones against the window.

Rage looked up, startled, but there was nothing to see. Her own reflection got in the way. She went close to the glass, looking through her shadow. Even the gnarled lemon tree that grew right outside the window was invisible. It was so dark that the glass might have been painted black.

The window shuddered under another onslaught, and the lights dimmed for a moment. Rage reached up to pull the curtain closed, wishing her uncle were home. He had left a note saying that he had gone out to check the fences and would not be back until late. That meant he had gone to the far paddocks, where the snow had pulled the fences down. Rage shivered. It wasn’t that she was afraid of being alone, but tonight the darkness was so thick that it might have been a black fog or some huge, dark animal prowling the night.

Rage turned the radio on as she set about washing the dishes. The radio announcer said that it was right on five-thirty p.m. and that the news would be coming up after the next song. Then a singer began to wail about being lonely to the sound of a twanging guitar. Rage dried a plate, thinking wistfully of the dishes she had washed whenever Mam cooked up one of her experimental seven-course meals. She thought of the night at the beginning of last spring when Mam had failed to come and get her from school. The way the headmaster’s shoulders hunched during the call to check with the police. She had wanted to run away from the room and not hear what he would tell her. But there was no use in running away from bad news.

The news had been of her mother’s car accident.

Mam was still in Hopeton General Hospital all these months later. When she had awakened from her long and dangerous coma to the amazement of the doctors and nurses, Rage had thought that it would be a matter of weeks before she would come home. But her mother had continued to grow paler and weaker, and now there was talk about moving her to Leary, where the hospital had better facilities and all sorts of important specialists.

Overhead, thunder cracked and echoed and the music fused into screeching and hissing. Then the radio went dead and the lights went out. Rage groped for the candle and matches that were on the sill in every room, but even as she took them up, the lights came back on. She set the candle in a bottle just the same and laid the matches by it in readiness. This was by far the worst winter since she and her mother had come to Winnoway Farm. In fact, it was the worst winter anyone could

remember,

according to the radio. Mam loved unpredictable, difficult weather. The only thing she didn’t care for were the sorts of perfect sunny days that most people seemed to spend their lives wishing for. She said there was no mystery in such days. But after

this

winter, Rage thought that even Mam might yearn for a simple warm day with a bright, clean sky. Rage wouldn’t have bet her life on it, though, because her mother was as unpredictable as the weather she loved.

The radio gave an asthmatic wheeze and came back to life. The announcer spoke in a fuzzy but serious voice about the dangers of black ice on the roads. Then he quoted statistics about how many car accidents had happened since the winter had begun. As he came to the end of the news, the radio screamed and died again.

Rage wiped the sink down, wondering if her mother was watching the storm and longing to be out in it. She had a bed by a window in Hopeton General, but the nurses said that she slept most of the time. Last weekend when Rage had visited the hospital, Mam had been half-dazed. Rage had asked the nurse what was wrong with her. The nurse explained gravely that her mother needed lots of quiet and calm, so they had given her medication to make her sleepy and relaxed.

As usual, Uncle Samuel hadn’t been in to see Mam; he just talked to her doctors. In the car on the way home, Rage had told Uncle Samuel what the nurse had said. That was when he had told her about the possibility of moving Mam to the Leary hospital. He said that there were two more serious operations that Mam had to undergo, one on her spine and one on her neck. But first the doctors needed to know why she wasn’t getting stronger, and they thought it would be better done at the bigger hospital.

Rage had wanted desperately to tell Uncle Samuel to go in and see Mam. She was sure that if her mother saw her long-lost beloved brother, it would be better for her than a hundred medicines. But the doctors had forbidden any shocks, and Uncle Samuel had told Rage that seeing him would be a shock to her mother, even if it was a good one. After that, there was no point in arguing because Uncle Samuel had spent his whole life rebelling against the things he had been told to do, and he blamed himself for what had happened to Mam. He was now so determined to do what was right, Rage knew she would never be able to convince him that in this case, the right thing might be

not

following the rules. If only there were someone to advise her. In stories there was always a true friend or an old, wise mentor who told you what to do.

Rage glanced over her shoulder at Billy Thunder sprawled on the mat in front of the potbelly stove and wished she could ask him for advice. But there was no telling what the big toffee-colored dog thought now. He seemed content to lie by the fire and to tag along after her or Uncle Samuel. There was nothing to show that he remembered the journey to the magical land of Valley, or that he missed his friends who had stayed there. But how could he have forgotten them? The little syrup-colored Chihuahua, Mr. Walker; the tan-and-white bull terrier, Elle; the neighbor’s goat, Goaty; and Billy’s own mother, the enormous Bear? She had thought she knew the dogs well before the firecat had lured them all through the enchanted bramble gate, but only after the dogs’ transformations into part-humans, when they had been able to speak with her, had she understood their true natures. Billy had become the most human, a boy of bright, complicated thoughts and clever ideas. Could he really have forgotten how much he had loved to think?