Winter Soldier (12 page)

Authors: Iraq Veterans Against the War,Aaron Glantz

Tags: #QuarkXPress, #ebook, #epub

One of the first things we noticed when we entered Tal Afar is that kids approached our vehicles fairly fearlessly. I asked my interpreter why and he told me they wanted soccer balls. Apparently, the unit before us had frequently taken soccer balls out and given them to the kids. Soon, we began to bring candy out in bags and the guys up in the turret of the Bradleys would throw it out the sides of the vehicle. The kids all rushed to the sides of the vehicle and hung out and fought for the candy. It was billed as a gesture of goodwill. There was also another motive: If the kids were around our vehicles, the bad guys wouldn’t attack. We used the kids as human shields.

Not long after we got to Tal Afar, we were told that two rival tribes had fought over control of the hospital in the city. The tribe that currently controlled the hospital, we were told, wanted us to provide security for it. So we started doing rotations at the hospital. There were already Iraqi army troops on the roof, inside the hospital, and at the gates. At first, we took over a room on the ground floor with hospital beds in it and that’s where we stayed.

As soon as we arrived, the hospital was attacked and the Iraqi army troops on the roof fired wildly into the neighborhoods. So within the few hours of us arriving, the hospital saw patients. A man came in shot through the chest; a boy came in shot through the leg. And the cycle repeated. Every time we would go out, people would mortar the hospital, shoot RPGs and small-arms fire, and normally the Iraqi army would fire back.

Eventually somebody suggested that staying in the hospital as a fighting force might be a violation of the Geneva Conventions. It was a sergeant who suggested that in the presence of an officer. And a few days later we moved to a government building about fifty feet away from the hospital. The hospital was still mortared because mortars are not very precise. Even when they were shooting at the government building fifty feet away, we were still drawing fire into the hospital.

Eventually, the first soldier in my platoon was killed by an RPG. After that, my unit left the hospital and moved to a different area of the city. Another unit in the regiment took over operations there and the Iraqi army troops remained stationed inside the hospital, on the roof, and at the front gate, under the guidance of American advisors.

In September 2005 we began a two-week-long mission Time magazine dubbed “The Battle of Tal Afar.” The army called this Operation Restoring Rights. The idea was to search the entire city, house by house, block by block, and clear it of weapons. Up until that point, we had permitted every adult male Iraq to keep one AK-47 for self-defense. With about two hundred thousand residents and several million dark windows from which to shoot, this wasn’t working well. So we swept through the city with around eight thousand Iraqi and American troops and began to search every house. We sometimes knocked down their front gates with our Bradleys, and occasionally blew them off the hinges with explosives. But usually we went from rooftop to rooftop and entered their homes from above. We separated the men from the women and the children, questioned people, checked their IDs, collected their weapons, and did fairly light searches of the houses.

At the same time, we cordoned off the southeast corner of the city, which was known as the Sari neighborhood. We had been repeatedly told that this neighborhood was an insurgent stronghold, so we gave the residents an order to evacuate their homes and provided camps outside the city for them to stay in. After that, we bombed their neighborhood for several days and nights using AC-130 Spectre Gunships, Apache helicopters, and tank rounds. The idea was that the insurgents would stay behind and fight while the civilians left. On September 10, the Kurdish militias entered Sari with U.S. Special Forces to clear the neighborhood of any remaining insurgents. As they began moving through, our troops entered to gather evidence of the insurgency and, in particular, of foreign fighters.

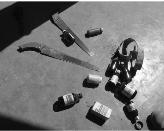

We were told to search Sari aggressively, to teach the residents a lesson: Don’t harbor terrorists. We knocked down doors, dumped drawers out, pushed furniture over, broke windows, and generally trashed the homes. In the end, my platoon found absolutely no evidence of foreign fighters; no weapons caches except common household items. This is a representative photograph of “evidence” of the insurgency. I was asked to take this photograph by the commissioned officer on the scene.

I remember someone said, “The saws might be used by terrorists to dismember bodies.” And the officer standing nearby asked suggestively, “Seriously, why would anyone have this many saws?” As though having wood saws was suspicious. In the end, we photographed kitchen knives, wood saws, some ragged old pistol belts, and empty bottles of antibiotics. After we had searched the entire Sari neighborhood ahead of schedule and found no resistance, someone in the chain of command came up with another suggestion. “Maybe the insurgents somehow escaped north to another neighborhood just past our checkpoints.”

So, we struck out on September 12 and sent the Kurdish militia in to round up every military-aged male from every house in another section of the city. We sat about five hundred men down in a large, barbed wire enclosure and stood guard as the families all gathered on the other side of the street. At that point, one of our interpreters sent a single anonymous, masked man in desert camouflage up and down the lines of men. He either gave a thumbs up or a thumbs down before each man he passed. Thumbs up meant the guy was a terrorist, thumbs down meant he wasn’t. In this way, we detained about fifty men from the group, zip-tied them, and in some cases wrote their alleged crime—“Cuts heads,” for instance—on their arm with a permanent marker. Another commissioned officer, Captain Noah Hanners, wrote “Cuts heads” on a detainee’s forearm and is quoted in the September 13, 2005, edition of the Washington Post as saying, “You get treated special today, buddy.”

One of the other statements made in the press around this time was by our squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Hickey. He was quoted in the Washington Post as saying, “We lose these people if we go in there and tear people’s homes apart,” which makes sense to me. It’s consistent with counterinsurgency doctrine, which places an emphasis on winning the support of the local population. But after Operation Restoring Rights ended, we continued our aggressive search tactics.

I decided to e-mail Lieutenant Colonel Hickey recently and I asked him about this. He replied, “The way you described being aggressive in our search, I would characterize as being disrespectful and counterproductive to what we were trying to do. I do not support tactics that ransacked homes.”

So where did things go wrong? There is no question that we ransacked homes and did so under orders. Equally, it’s clear to me that this kind of behavior was not consistent with counterinsurgency doctrine, in which Colonel H.R. McMaster, the commander of our regiment, was clearly well versed.

I have to conclude that even in the best of situations in Iraq, civilians still die, questionable decisions are still made, the insurgency still rages, and in the end the only war our country has waged well is a propaganda war on its own people.

Specialist, United States Army, Florida Army National Guard, Infantry, Bravo Company, 2nd of the 124th Infantry

Deployment: February 2003–January 2004, Kuwait, Qatar, Balad

Hometown: Orlando, Florida

Age at Winter Soldier: 36 years old

I was a military brat. My father served two tours in Vietnam and is currently rated 100 percent disabled by the Veterans Administration due to PTSD and Agent Orange exposure.

When I deployed to Balad, my unit was tasked with gate and perimeter security at Camp Anaconda, the largest of the enduring bases in Iraq. We were tasked with clearing Iraqi nationals who worked on post, doing such jobs as filling sand bags, clearing rubble and trash, etc.

These Iraqi nationals were paid a dollar a day and were given an MRE for lunch. They worked under extreme conditions of heat and dust, oftentimes 130-degree temperature, and were always escorted by armed guards. Every morning, the Iraqis that wanted to come on post to work were herded into a barbed wire enclosure. Almost every day, they would start pushing each other into the barbed wire. In order to get them to stop doing that, we used physical force. This included shoving, stroking Iraqis with the butts of our weapons, and threatening them with bayonets. There were several occasions when we locked and loaded our weapons and told them if they didn’t stop pushing each other that we were going to open fire.

One of our other responsibilities at the front gate was to search the several hundred dump trucks and semitrailers that were coming on post every day. The dump trucks were also driven by Iraqis. We usually had one or two interpreters on duty with us, but inevitably there would be miscommunication.

One day, an Iraqi dump truck driver didn’t understand that he was supposed to stop and continued forward in his truck. My team leader interpreted this as a hostile action, ran over, yanked him out of the truck, and the rest of my team responded. We beat the crap out of this guy, pushed him down in the dirt, detained him, roughed him up, and told him that he was not allowed to come back on the post for at least a month. I don’t know what he did for the next month.

We also raided houses. One of the first houses we raided was supposedly the home of a former Ba’ath official. It was the middle of the day when we arrived in the neighborhood. The raid started when the armored cavalry unit that was with us rolled over the front wall of the house. I was second in the stack formation of troops that went through the gate. There was an older female who was in the courtyard and she was screaming something unintelligible in Arabic. One of the soldiers behind me apparently thought that she was a threat. He butt stroked her in the face, knocked her to the ground, and someone after him zip-tied her and took her out into the front yard.

We proceeded to ransack this house. I was in the master bedroom. There were dressers and wardrobes; the wardrobes were locked. We pulled the doors off. We turned everything in the room upside down. We went through everything. Personnel in my unit that were in the kitchen turned the refrigerator upside down and broke the stove: pulled it out of the wall, broke the line to it. After, we searched through the house and we had everyone including the children zip-tied on the front lawn. Then someone in my chain of command realized that we had the wrong home. We were on the wrong street. The home we were supposed to have raided was actually behind this house on another street.

So we went and raided that house. Going through the gate of that home, I almost fired on a person that was mentally disabled. He was standing in a window directly in front of us and he didn’t understand what was going on. I almost fired and then realized that there was something wrong with him and he just didn’t realize what was happening.

We searched through that home, detained the person that we were supposed to detain, and started coming across all this paperwork in his office and his bedroom. It looked to me like he was an algebra instructor, maybe at the local high school, maybe at a local university, because there were reams of paper that were just math problems. This guy was supposed to be a former Ba’ath official.

We took him, put a sandbag over his head, loaded him on a truck, and started back toward Camp Anaconda. He was on my vehicle with my squad and on the way back to Camp Anaconda—it was about a forty-five-minute drive—my squad leader thought that it would be funny to pose for a picture next to this guy. He asked me to take a photo of him and this detainee, but I refused to do so. Upon arrival back at our quarters, I was disciplined, including physical punishment, because I had disobeyed him in front of the rest of the squad.

The turning point for me in Iraq was an incident that occurred when I was off duty at night. There was a “hard core” platoon in my company. Every unit has one platoon that is more extreme than the rest. This platoon happened to have a squad that was attacked while they were hiding out in the farms in the surrounding area, trying to detain people who were out past curfew.