Wobble to Death (4 page)

Although the atmosphere in the area of the huts was wors-ening, conditions on the track had improved during the day. The gas was now on again, and much of the fog had receded. Officials still stamped their feet and complained of the cold, and the runners were still mostly well-covered in layers of clothes. But the presence of two thousand or more shilling spectators injected some warmth of spirit into the occasion. Knots of enthusiasts roared encouragement and abuse at the contestants, occasionally inspiring or goading one to complete a quicker circuit. Betting was heavy, chiefly on the two ‘inside’ men, and Chadwick was firmly reinstated as favourite. He completed his ninetieth mile shortly after 7 p.m., only twenty minutes behind his rival, Darrell. Three-quarters of an hour later O’Flaherty and Williams followed. Chalk and Reid passed the same point shortly before 8.30 p.m., and seven stragglers followed during the next two hours. Mostyn-Smith strolled serenely on, scheduled to reach this landmark at 1 a.m. on the following morning.

Walter Jacobson paced the area behind the stands. Unlike Sol Herriott, he was not a man who believed in being the centre of public attention when he was in charge. Experience of management in several of Herriott’s sporting enterprises had taught him that it was prudent to move into the shadows when Herriott was away, for that, inevitably, was when problems and complaints would arise. He justified this shunning of the limelight by telling himself that he was ‘making a check.’ Why, somewhere on his rounds he might surprise a workshy member of the Hall staff who could be detailed to clean Mostyn-Smith’s hut.

As he neared the side of the Hall which housed the restaurant and offices, Jacobson decided to check that the evening’s takings had been locked away. In the boardroom where the safe was kept, there was a set of decanters. A glass of madeira would be warming after his tour of the perime-ter. He turned into the staff corridor, and stopped. From the kitchens came shouts and screams of panic. Fearful of what he would find, he ran through the almost empty restaurant, flung open the service door and was enveloped in black smoke.

‘Shut the bloody door!’ someone shrieked. From the ovens flames leapt to the ceiling. Two or three of the kitchen staff were standing in pools of water trying to control the fire with water drawn from the taps.

‘The hydrant!’ Jacobson shouted. ‘In the corridor!’

By an unaccustomed stroke of fortune he had remem-bered that hydrants in various parts of the building were connected with a reservoir containing 5,000 gallons. A hose was played out, and in a minute a jet of water leapt to the source of the fire.

A short while later they stood ankle-deep in a blackened room, surveying the damage, which was worse in appear-ance than in fact. The cause, Jacobson discovered, was care-lessness on the part of an inexperienced girl, using a bowl of fat near a flame. She was unhurt, but shaken.

‘How long are you on duty for?’ he asked.

‘Till six tomorrow, sir.’

‘Do you live near by?’

‘Very close sir, in Parkfield Street.’

‘Get home and rest then, for an hour. We’ll take you out of the kitchen tonight. Give you a chance to recover your-self. When you return see me personally. There’s a job that you can do in another part of the building.’

‘Very good, sir. Thank you, sir.’

Jacobson dutifully admonished the head cook for failing to recognise the danger in allowing the girl to move the fat. Then he left the kitchen staff to restore the room to nor-mality. In the staff wash-room nearby he wrung out his socks and tried to brush the odour of smoke from his clothes and hair. He thought of Herriott dining out in luxury; of Mostyn-Smith’s threat; of the stupid face of the cook; of the prospect of a night with his feet damp and numb; and he swore again, repeating the earlier obscenity, slowly, four times.

The Pedestrian Contest at Islington

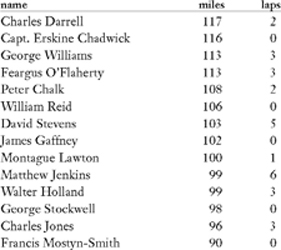

POSITIONS AT THE END OF THE FIRST DAY

P. Lucas (78 miles) and J. Martindale (61 miles) retired from the race.

A BELL WAS RUNG at 1 a.m. to signal the end of the first day’s running—or the beginning of the second, depending on how one mentally approached the race. Its none too cheerful clanging in Jacobson’s hand interrupted the trance-like atmosphere in the Hall. Several competitors either stepped off the track or looked hopefully around for their attendants. Sam Monk wrapped a horse-blanket around Darrell’s shoulders and guided him to his tent nearby. In the last hour Darrell’s progress had slowed markedly, and blis-ters seemed to be the cause. He had stopped two or three times to adjust his boots, and finally flung them away and continued barefoot.

‘No matter,’ his trainer reassured him. ‘I’ll wrap a calf’s bladder round that foot when you begin again. Like running on velvet, that’ll be. Three hours’ rest, and you’ll be out on track for the next hundred.’

Erskine Chadwick wearily completed another lap before marching across the arena to accept Harvey’s ministrations in the second tent. He approached his athletics much as he approached service as a Guards’ Officer; other ranks should not be permitted to see that their superiors, too, required rest. But in quarters, as it were, with only the discreet Harvey present, he flopped gracelessly across his bed, groaning. Running had been a novel exercise. Now his mus-cles were registering their protest.

‘It can’t go on like this,’ he groaned, as Harvey pum-melled the stiffening limbs. ‘Walking, yes. I can give any man alive five miles in a hundred on the open road. But this damned circus . . . My lungs must be ruined by now. Cigar smoke, fog, gas fumes, cattle dung. How can a man practise athletics in these conditions? I tell you, Harvey, I doubt whether I shall go on tomorrow.’

‘But you must, sir. You’ve never given up before.’

‘Never felt as bad as this,’ Chadwick muttered. ‘It’s not really the legs or the feet, though they ache appallingly. I think it’s the effect on the brain of endlessly running in small circles.’

‘Darrell can’t last long,’ Harvey consoled him. ‘Fair hob-bling he was this last hour. Blisters’ll finish him. Surprised me to see that. Monk shouldn’t let him run barefoot. Tear his feet to pieces, he will.’

‘Pour me some claret, man, and leave me to get my rest. But let me know when Darrell goes back on the track. I must keep up somehow. And turn out the gas.’

Harvey was deeply depressed as he fixed the tent-flap and left Chadwick lying on his bed with mouth gaping, breath-ing heavily, the claret untouched on his table. Years of serv-ice to this peevish ex-soldier had instilled a fierce loyalty in Harvey. He knew very well that for the first time in his life Chadwick was mentally preparing for defeat.

There was now little activity on the tracks. Most of the first day’s survivors had been happy to follow the example set by the star performers. The lion-hearted Billy Reid tottered on in the lowered gaslight, remembering his brother’s words before he left for a sleep in the hut: ‘Keep at it when the oth-ers stop, Bill. Every step then is a yard in credit.’ Another who persevered was Mostyn-Smith, humming cheerfully to himself to sustain the rhythm of his march. A new team of officials had taken over the watches and lap-scoring.

Sol Herriott had returned to the Hall soon after mid-night, listened to Jacobson’s account of the fire, and shaken with laughter.

‘I arranged it all before I went, Walter. Didn’t I warn you about a fire?’

Jacobson mustered a weak smile, secretly hating his fat superior.

Herriott altered his tone.

‘You acted splendidly, old man. It could have ruined the whole promotion if a panic spread through the building. Damn it, you still reek of smoke. Get along home for a change of clothes, Walter. I’m quite capable of managing here for an hour or so.’ He flicked cigar ash behind him casually. ‘No likelihood of another fire. I’ll check the tents and huts, though. These addle-brained foot-racers probably hang their clothes over the gas to dry them.’

SHORTLY BEFORE ONE-THIRTY Sam Monk left Darrell’s tent. His movement through the half-light to the Liverpool Road exit was not observed. Outside, a hansom was waiting. He climbed in briskly, sat back in the darkness and relit a cigar that Herriott had given him earlier. The cabby cracked his whip and in seconds Darrell’s trainer was being borne at speed away from the Agricultural Hall and northwards through Highbury.

SHORTLY BEFORE ONE-THIRTY Sam Monk left Darrell’s tent. His movement through the half-light to the Liverpool Road exit was not observed. Outside, a hansom was waiting. He climbed in briskly, sat back in the darkness and relit a cigar that Herriott had given him earlier. The cabby cracked his whip and in seconds Darrell’s trainer was being borne at speed away from the Agricultural Hall and northwards through Highbury.

The cab drew up after twenty minutes in a long street of recently built terraced houses in Finsbury Park. Monk set-tled his fare, made some arrangement with the driver and stepped quickly across the pavement and up the tiled path to the porch of a house. He held a key ready and had let him-self in before the cab trundled away.

He stood in a darkened, stone-floored hallway and waited, while his eyes adjusted and identified a pot of ferns to his left and a monstrous hall-stand beside it. He deposited his cap and overcoat, felt blindly for his tie and straightened it, groomed his hair with his palms, which he afterwards brushed on his trousers, and called aloud, ‘Which way?’

A woman’s voice answered: ‘In here.’

Monk found a line of light which broke the regularity of the wainscoting, and fumbled above it for a door-handle. He let himself into a large drawing-room, lit by gas, but mainly illuminated by a well-banked log fire, which glowed orange and flickered in miniature on a dozen glass ornaments and on the polished surfaces of ornate dark-wood furniture. The ceiling was high, but the movement of the flames glowed there, too. Over the marble mantelpiece, in place of a mir-ror, was a broad presentation belt, glittering with studs and silver embossments.

Monk stood by the door, reluctant to step from the stained floorboards on to the small island of carpet in the centre. If Monk had been a sensitive man, his hesitation might have had some symbolic significance. For the occu-pant of the tufted island, smiling from a velvet sofa, was Cora Darrell.

‘You are very punctual,’ she said. ‘Would you like a chair?’ ‘Thank you. I’d rather sit on the footstool here and warm myself for a while.’

‘What was happening when you left?’

‘Not very much,’ Monk answered. ‘He’s sleeping till four. Should sleep content, too, for he’s in the lead.’

‘He is all right, Sam?’

‘Oh, pretty good, pretty good. A spot of foot trouble towards the end, but that will pass. If he needs encourage-ment he only has to look at Chadwick. I never saw a man so beat at the end of one day.’

For some seconds neither spoke. A clock under a glass dome on the mantelshelf chimed the hour. Monk spread his hands to the fire and rubbed them vigorously.

‘You say four,’ Cora said. ‘That isn’t long. You must leave by half past three. Have you arranged a cab?’

He stood, warming the backs of his thighs.

‘Of course. Are you tired? Did you enjoy your dinner out?’

She smiled towards the fire.

‘The meal was excellent, but I could have wished for dif-ferent company. One day I shall persuade you to escort me for an evening.’

‘I like this arrangement better,’ said Monk. ‘Let them with the money provide the food and wine. I supply what you don’t want from them. Ain’t that so?’

He had perched himself on an edge of the sofa and was raising her face in his open palms. Cora allowed Monk to kiss her.

‘And what,’ she murmured, ‘have you brought to break my resistance?’

Monk grinned with the confidence of a suitor who has already stated the time available for love’s preliminaries.

‘As it happens, I did bring this. Where are the glasses?’

From his pocket came a flask of whisky, which Cora may well have seen earlier in her husband’s tent, with other rubs and embrocations. She pointed to a cabinet sideboard on which glasses were waiting. He filled them generously, giv-ing no thought to Darrell’s deprived limbs.

‘My name should be on there,’ he said, indicating the cham-pion’s belt above the mantelpiece. ‘Fifteen years back, or less per-haps, I ran Johnny White, the Gateshead Clipper, ten miles at Bow Running Grounds. Could have beaten him easy after six. He wasn’t the same man who thrashed Deerfoot. Out of form, he was, and I was twenty and going full bat. Then they offered me fifty to run to the book. Like a mug I agreed. Johnny won in slow time and kept the belt till Young England thrashed him. I’m glad it was Charlie who finally won it outright, though. I’m out there with him, when he runs, every yard.’

‘Except when you take his place here,’ said Cora, laugh-ing. ‘Take my drink, Sam. I’ve already drunk enough this evening.’

Monk drained his own glass, and then Cora’s.

‘There ain’t much time,’ he said. ‘Let’s get upstairs.’

She was shaking her head.

‘I wouldn’t like that, Sam. Why do you think I banked the fire up in here? The bed is cold. This is different, anyway. Charles has never approached me here. Here, Sam. Love me in here.’

Monk was feeling warm for the first time in twenty-five hours and readily acquiesced. He draped himself along the sofa and kissed her resolutely.

Minutes later Cora knelt before the fire while Monk began the tantalising work of disrobing her. She had slipped off her shoes, but the rest was left to him. His fingers coped haltingly with hooks and eyes and tiny buttons. The dress bodice eventually fell.

‘Warm your hands again before you touch my camisole,’ she commanded him between giggles, squealing as his hands gripped her shoulders and he buried his face in her neck.

‘Bows, Sam. They shouldn’t trouble you so much. Here, I’ll pull off a stocking while you untie them.’

The next layer presented its own problems.

‘Leave the corset, then, and I’ll manage my skirt and pet-ticoats,’ she offered. ‘Turn out the gas.’

When he turned she was stepping from a frothy moun-tain of petticoats. Monk gathered himself. There remained the corset. The rest would not be difficult.

She gasped with relief from constriction as the unlacing progressed. And finally corset, white chemise, lace drawers, black silk stockings and garters lay scattered.

‘If I had the patience and time,’ whispered Monk, ‘I’d make you undress me.’

Instead he stripped himself in seconds, and lifted her gen-tly back to the sofa.

‘I think you’re right,’ he said. ‘Much better in a warm room beside a fire.’

FEARGUS O’FLAHERTY GRUNTED, turned on his side and sniffed again. He felt sure that he had not been sleeping long. It could not be one of his dreams, he was certain, for he remembered the race, his aching legs and the hut. Nothing was going to make him leave the warmth of that bed; not for three more hours, anyway. But what was that blasted smell, which had not been there before? He opened his eyes reluctantly and looked across to the bed that Mostyn-Smith had been allocated. It was still empty. That greenhorn would probably walk all night. He’d need to if he was going to make a hundred miles. Grinning contentedly, the Irishman closed his eyelids and began to drift back to unconsciousness.

FEARGUS O’FLAHERTY GRUNTED, turned on his side and sniffed again. He felt sure that he had not been sleeping long. It could not be one of his dreams, he was certain, for he remembered the race, his aching legs and the hut. Nothing was going to make him leave the warmth of that bed; not for three more hours, anyway. But what was that blasted smell, which had not been there before? He opened his eyes reluctantly and looked across to the bed that Mostyn-Smith had been allocated. It was still empty. That greenhorn would probably walk all night. He’d need to if he was going to make a hundred miles. Grinning contentedly, the Irishman closed his eyelids and began to drift back to unconsciousness.

Suddenly the warmth drained from his veins. His limbs tensed and he held his breath. In the hut he could distinctly hear the sound of breathing. And Mostyn-Smith’s bed lay undisturbed. O’Flaherty slowly lifted his head from the pile of clothes which served as a pillow and looked along the length of the bed towards the door, which was slightly open. His eyes swivelled to the right and left, but nobody was vis-ible. His head dropped heavily back on the pillow and he lis-tened again.

The breathing was still there, more urgently now, and the smell had returned. But what made O’Flaherty’s eyes bolt wide in horror was a second sound, a powerful scratching on the stone floor, the unmistakable movement of something large, heavy and alive, steadily towards his bed. With a yell of fear the Irishman leapt upright on the bed—or almost upright, for in rising he crashed his head on the hut roof, groaned and collapsed. The young girl who had been detailed by Jacobson to scrub the hut screamed, jumped to her feet and bolted for the doorway, crashing over her pail of liquid carbolic as she went. O’Flaherty lay dazed and groaning. When he recovered enough to open his eyes again they focused on a scrubbing-brush lying in a pool of carbolic. He crossed himself, swore violently and bundled the bedclothes over his shivering body and head.