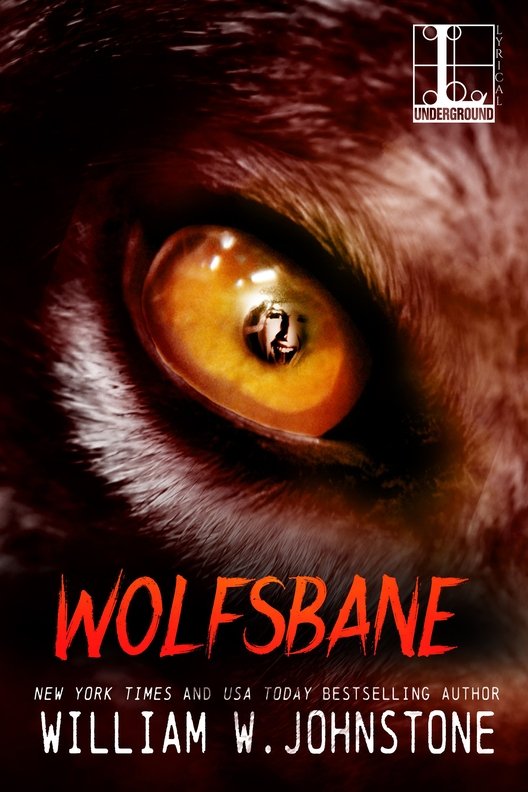

Wolfsbane

Authors: William W. Johnstone

Wolfsbane

W

ILLIAM

W. J

OHNSTONE

ILLIAM

W. J

OHNSTONE

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Copyright Page

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Copyright Page

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Prologue

Ducros Parish, Louisianaâ1934

Â

Â

Only an hour remains until dawn in the bayou country. The moonlight has wanned; only a memory as the light from the crescent orb has served another night and moved on to please yet another master.

But it is unnaturally silent as dawn approaches. The singing of birds is absent. Insects are still. Animalsâof the four-legged kindâremain motionless in their lairs.

Then a figure, slightly hunchbacked, emerges cautiously from the brush. Tuffs of hair cover the face, reddened eyes peer animal-like from slanty sockets, and the creature's clothing is torn and muddy.

The creature suddenly throws back his head and howls, exposing fanged teeth.

The shouting of men silences the howling. The creature drops to all fours and snarls, saliva dripping from its mouth. What is left of his shirt is ripped at the chest, exposing a five-pointed star: the pentagram that signifies the mark of the human/beast.

The impression is dark and permanent: burned into the flesh from birth by an invisible iron, held in the smoking hands of the devil.

The shouting of the men draws closer and the creature not only can hear the marching footsteps, but can smell the scent of humans on the hunt.

For him.

He tries to run as a seizure grips him in an iron fist. He foams at the mouth and cries out, writhing on the ground, damp with dew. He beats his hairy fists on the earth, drumming his animal-like feet on the ground.

Then, as his spasms taper off into a trembling, men stand over him as his features change. The hair on his face has disappeared, leaving smooth skin. His hands ungnarl, becoming once more human. His eyes lose their beastlike, slanty redness and his back straightens.

A man raises his rifle, levering a round into the chamber. He looks into the eyes of the man on the ground. “Claude Bauterre, I am sorryâbut you have to die.”

Claude Bauterre gazes upward at the man. His eyes are calm. He is silent.

“Die, Bauterre!” a man yells.

Claude Bauterre laughs as his eyes take in the men forming the circle of death around him. His laughter echoes through the bayou. He laughs as the men empty their rifles and shotguns into his body. The ground beneath and around him grows red and soggy from his blood. The first rays of sunlight touch the bayou country.

His bullet-riddled body is wrapped in a tarp and carried to a cart on a nearby road and transported to the Church of Our Lady of Peace. There, a priest stands, waiting for the return of the men. The priest lifts one corner of the tarp and gazes at the bloody corpse.

“Take him to the blacksmith's shop,” the priest orders. “Burn what is left of him to ash.”

“And then?” a man asks.

“Seal the ashes in a thick steel box and bury him; seal the grave with concrete. All around him.”

“His wife will want the burial in the family plot,” the priest is reminded.

The priest battled with his conscience, then nodded his head. “She had nothing to do with the making of this monster. . . .”

“She's a witch!” a man shouted. Other men nod their heads in agreement.

“No!” the priest returns the shout. “We don't know that. I cannot deny her the right to have her husband buried in the sight of God. Go! I will be along soon. Now I must see this . . . creature's wife.” He walked back into the church.

All that day the men of the village stoked the fires at the local

forgeron's

shop, burning the body of Claude Bauterre. The ashes were black.

forgeron's

shop, burning the body of Claude Bauterre. The ashes were black.

“Comme péché,

” a man said, wiping the sweat from his face.

” a man said, wiping the sweat from his face.

As sin.

But at the mansion, Claude Bauterre's wife would not admit the priest. She sat in the darkened plantation house and refused to see him. The priest hammered on the door, shouting out for her to admit him.

She would not.

He prayed on the steps of the mansion.

Inside, the woman laughed at him, her laughter echoing about the raging October storm that lashed the bayou country, her taunting dark mirth shattering his prayers.

“I have a son!” she screamed at him. “I have a daughter. And they will not rest until their father's death is avenged.”

“He was a monster!” the priest shouted at her, his face slick from the driving rain, his dark hair plastered to his skull. “He was evil!”

She screamed obscenities at him.

“He was possessed by the devil. You know that is true. Claude Bauterre killed by night.”

Her screaming was joined by that of her children. The evil howling chilled the priest and he shivered on the steps of the great house. He bowed his head and prayed for strength and guidance.

“Get out!” the woman shrieked at him. “Leave these grounds or die!”

Father Huval backed away from the steps of the mansion as lightning danced over the swamps and bayous. He raised his Bible to the house and prayed. But his prayers could not match the black, evil chanting of the woman in the house; the storm seemed to draw strength from her words. When the children joined in, the storm hit its fury, the winds screaming.

Father Huval ran to his buggy, parked in the drive. He lashed the horse into a run and raced back to town. At the church, he gathered a few men around him and told them what must be done. They agreed and picked up their guns, following the priest back to the mansion. There, they physically drove the woman and her children from the mansion. In the still-pouring rain, Father Huval told the woman, “See your beast/husband put into the ground, Madame Bauterre, and then get out. Never return to this village.”

She screamed and spat at him, the boy and girl by her side following her actions. From the windows of the great mansion, servants watched impassively.

She was allowed to pack a few belongings and then was escorted to the graveyard. There, with her children, she watched as Claude Bauterre's ashes, encased in a steel box, were entombed in concrete. Mother and children stood silently as the priest prayed for God to forgive the man being buried and the men who had taken his life.

Father Huval turned to the woman. “Get out!” he told her.

“I'll be back,” she hissed at him, her eyes dark with rage.

At gunpoint, the woman and her children were escorted to a waiting car.

The years of terror had ended. At least, that is what was hoped.

The Bauterre mansion remained void of life for years, except for a caretaker and two servants. In 1945, the oldest child, Claire, returned to the mansion and delivered her only child, a girl. She named her Janette. The second-born of Claude and Victoria Bauterre returned to the mansion two years later, with his wife. Their only child was delivered in the home. A boy, he was named after his grandfather. He died on his eighth birthday. His mother killed herself. The father went insane. So the story went.

Janette Bauterre Sievert and Claude Bauterre, brother and sister, were born at night, within seconds of the other's birth, very close to midnight, on the last day of October. It was always storming, the winds howling like a demon.

And along the bayou trail that had soaked up the blood of Claude Bauterre, years before, wolfsbane grows each October. All along the trail. Without fail.

And every October, without fail, strange sightings are witnessed in Ducros Parish, Louisiana. Beastlike creatures, half man, half animal, who prowl the bayous and howl at the moon.

Chapter One

Ducros Parish, Louisianaâ1976

Â

Â

“What the hell is that smell?” the fisherman asked, his nose wrinkling in disgust.

“Damned if I know. Whew! Push us off, Roy. That's making me sick to my stomach.”

“Paul?” Roy said, turning a little pale around the mouth. “Look to your right and tell me what you see. Just past that stob sticking out of the water.”

Paul looked. And looked. “Nothing,” he said. “What was I supposed to see?”

“I don't know,” his friend muttered. “It's gone, now. But I've never seen anything like it before. Never. Except in . . . ah! Forget it.”

“No, come on, Roy. What did you see?”

“A thing.”

“A thing?”

“I think it . . . must have been a bear.”

“There's sure bear in here. But that wasn't any bear, Roy. If he'd run off, we'd have heard it. All that brush over there . . . sound like a freight train goin' through it. And bears don't smell like that smell. You said something 'bout âexcept in.' What'd you mean by that?”

“Well,” Roy sighed. “It . . . looked like a man with hair all over his face. Ugly. Scary-looking. And it had pointy ears, too.”

Paul started laughing.

Roy's face reddened. “Well, goddamnit! I know what I saw. And I told you what I saw. So if you don't believe me, then screw you!”

“Whoa!” His longtime friend held up his hand, his laughter fading into the swamp. “Easy, friend. We're buddies, remember? You're serious, aren't you?”

“You still smell it, don't you?”

His friend sniffed. They were seventy-five feet from the bank and the odor had faded. But it was still in the air. “Yeah, I do. But that was no bear, Roy. No way. He would have made some noise gettin' away from us. You know that. We've hunted bear all over, and we've seen plenty of them.”

“Yeah, you're right. Sure, you are. Hell, I guess it was something else and my imagination just took off with me. Kinda tired; been fishin' all day.” He laughed, patting the top of the ice chest. “And hittin' the beer pretty good, too.”

“Let's cut out of here, Roy-boy. Go on back to the lodge. It's been a long day. . . . I'm tired, too.”

In the murkiness of the swamp growth, eyes watched them leave. Animal-like ears flicked at a fly, and drool dripped from a fanged mouth. The beast snarled softly, then dropped back onto the ground, curling up, to rest until full darkness. Then he would hunt.

Â

After supper, Roy walked down to the water's edge. He had seen the camp owner head that way, and he wanted to talk to him.

“Mr. Guilbeau?”

“Down here, son,” the man answered. “Over by the boathouse.”

Roy followed the sound of the voice and located the man. He stood for a moment in silence, trying to collect his thoughts; trying to put what he wanted to ask in such a manner that the man would not think him a fool.

“Have you lived here long, Mr. Guilbeau?”

“All my life. All sixty-one years. My family been on this bayou for two hundred yearsâgive or take a few. Come down from Canada 'bout 1778, I tink it was. When New Iberia was founded. Yeah. Why you ask?”

“Mr Guilbeau . . . I don't want you to think I'm drunk, or crazy, but I saw something late this afternoon. ”

“What you see?”

“Well . . . after my buddy laughed at me, I pretended that maybe I didn't see it. Too much beer, too much fishing, you know. But I saw it. And I've never seen anything like it before in my life. Except in the movies.”

Guilbeau straightened up and looked at the man. “You still ain't tole me what you seen.”

“I saw . . . I saw . . . a half man, half beast,” he blurted.

“Did you now?” The fisherman and camp-owner's voice was as soft as the bayou under moonlight. “Where you see dis ting you see?”

“Right off that bayou where you took us that first day over here. Down that chute. And there was an odor about this thing. A real bad smell.”

“Ummm. Maybe you seen the swamp man, huh?”

“Swamp man?”

“Oh, shore. We got swamp men. People been seein' swamp men 'round here for long time. Hundred or more years. Got 'um over in the Honey Island Swamp, too. We've had scientists in this part of Louisiana from all over lookin'. Just lak the Bigfoot up in the nortwest. Don't hurt nobodies. Jist curious, at's all.”

Roy laughed, his tensions easing away. “You mean, you believe in folklore? You believe in swamp men?”

“Shore.” The Cajun grinned good-naturedly. “But I tell you what: if I was you I wouldn't go back to where I seen the ting. He might be hongry, eh?” He punched the Mississippi man lightly on the arm and winked.

“You don't believe me, do you?”

“Yeah, son,” Guilbeau said. “I

do

believe you. Me, I seen him plenty times. But I don't go back

where

I seen him for tree, four days. Jist to be on the safe side, you know?”

do

believe you. Me, I seen him plenty times. But I don't go back

where

I seen him for tree, four days. Jist to be on the safe side, you know?”

“Well,” Roy said, not knowing whether to believe Guilbeau or not. “Okay. But I did see something.”

“'At's rat, you seen someting. But it din hurt you. Din try to bother you none. He don mean you no harm. Jist curious, at's all.”

Roy stuck out his hand and the older man shook it. “We're pulling out early in the morning, Mr. Guilbeauâheadin' back to Hernando. We've both enjoyed it here. Fine fishin'. And,” he smiled, “I won't say a word about what I saw . . . to anybody. Believe me.”

“'At's good.”

When the man from Mississippi had faded into the night, Guilbeau went to his office in the now deserted lodge and picked up the phone, quickly dialing a number. “Trahan? Where is that idiot boy of yours? Naw, don tell me he's chained. One of my tourists seen that fool late this afternoon. You shoulda put that boy in the asylum years ago, Louie. Now I'm gonna tale you someting: that idiot boy of yours scare jist one more of my fishermen, run off my business, I'll call the state and have him put away.”

Guilbeau listened for a moment. Despite himself, he felt a cold finger of fear touch his belly.

“Louie! A man from Mississippi

seen

him. Don lie to me, Louie. Okay. Fine. I see you later.”

seen

him. Don lie to me, Louie. Okay. Fine. I see you later.”

Guilbeau turned to look into the eyes of his wife, standing behind him. “Trahan's poor child loose again, Eddie?”

“Louie said no. Said he's been chained all day long. He took an oath he was speakin' to me the truth.”

She put a hand on his shoulder. “Eddie? Call the sheriff. It's past time. It's not fair to the boy to be kept chained up like he's been. There ain't no hope for the boy, I don care what Louie believes . . . there ain't no hope for him. Now you either do it, or I'll call the priest and tell him about it. I'll call him right now.”

“You rat, Jenny.” Eddie grinned. “As usual. Yeah. Dat dog-boy belong in a place where he can get hep. Treat dat disease he got. But Jenny, if it wasn't Trahan's dog-boy . . . who was it? Or . . . what was it?”

Fear darted across her face. She quickly crossed herself. “Don't you start, now, Eddieâdon do it. I won't have it . . . no more it in this house. I mean it.”

“If I din know better, I'd bet you a Bauterre was behind all it . . . whatever it is. Goddamn 'em all!”

His wife paled as the blood rushed from her face. Her husband watched as her face mirrored her dread.

“What's wrong wit you, Jenny?”

She shook her head. “All the bad Bauterres is dead, Eddie. You-all killed them forty year ago. Least you say you did.”

“Relax, mommaâcalm yourself. Claude Bauterre was the last of the bad ones. He's dead. We shot him more'un fifty time and took him to Blanchet's Funeral Parlor. We burned him to black ash and sealed the ash in a steel box . . . burried him in tree feet of concrete.” He pointed. “Rat over there in the graveyard. Rat where he's been since turdy-four.”

His wife shook her head.

“What you meanâ

non!?

I hepped do it.”

non!?

I hepped do it.”

“Madame Bauterre is back,” she said.

“Back here?” The question was almost a shout.

“She come back las week. Open Amour House. Talk is she's gonna stay.”

“How come nobody seen fit to tale me 'bout dis?”

Jenny shrugged as only a Cajun can.

“Old Victoria mus be at least ninety! Who she bring wit her?”

“A lady servant. I ain't seen her. But I heard she jus lak Madame Bauterre. And you know what I mean.”

Eddie ignored her last sentence. He shook his head in disbelief, astonished the old woman was still alive. But, should he be surprised? Since she was a . . . He refused to even think the word. But the fact that she was back chilled him. He shook off the feeling of dread.

“Ninety year old and come back.

Faible?”

Faible?”

“Non.

Not feeble at all. Gets around good, so I was tole.”

Not feeble at all. Gets around good, so I was tole.”

He looked at his wife. “Jenny, you holdin' someting back from me. What else you hear?”

“Things been seen, Eddie. You know what I mean. Just lak that tourist seen today.”

Eddie fought back the rising fear in him. It was far too early for the swamp men to appear; they always came out in October. Ever since . . . He willed his mind not to remember that night. His mind refused to obey. They had been seen ever since that early morning so many years ago.

“Where you hear all dis talk?” he asked his wife.

She sulled up, refusing to look at him or reply.

“Come on, Jennyâyou tale me, now. Hear?”

“Annie Metrejean,” she mumbled.

“Aw, shit!” Eddie turned away. “I tole you and tole you to stay the hell away from dat woman. She's crazyl”

“Is she, Eddie?” Her eyes were serious. “Eddie, I'm scared. Papa was wit you men in turdy-four. Where is he? Why ain't he been around lak he usually do? How come we ain't seen him in three, four days?”

He put his arms around her and patted her trembling shoulder. “I'll ride out to his place in the morning, Jenny. Check on the old man. He's awrat. Probably fishin', is all.”

“Annie Metrejean says bad tings gonna happen in Ducros . . . soon. Says they alratty begun in some ways.”

“Jenny,” he said, holding her close, hoping his own fear would not transmit itself to her. “I want you to stay 'way from Annie. She's gittin' you all worked up 'bout nuttin'. But he seriously doubted his own words. Madame Bauterre had said she would be back, and she would have her revenge. He pushed that thought from him. ”Annie is jist as badâin her own wayâas them damn Bauterres was.”

“Non!”

She pulled away from him, spitting the denial at him. “She's rat and you know it. She sees and hears tings we don't. Everbody knows that. You know well as me who tole Sheriff Cargol 'bout Claude Bauterre. Annie Metrejean did. Said he wasn't no bad person. Said the sheriff was pickin' on the wrong person. And she was rat, wasn't she?” she glared at her husband.

She pulled away from him, spitting the denial at him. “She's rat and you know it. She sees and hears tings we don't. Everbody knows that. You know well as me who tole Sheriff Cargol 'bout Claude Bauterre. Annie Metrejean did. Said he wasn't no bad person. Said the sheriff was pickin' on the wrong person. And she was rat, wasn't she?” she glared at her husband.

“I don know, Jenny. I don know what to believe no more. I don know whether the old ways was rat or not. I don know whether Annie is a

sorcière

or not. She ain't lak us, I know 'at much. Prowls the bayous at night; goes into places wit her pirogue where big men won go. Believes in the old ways; won turn loose.”

sorcière

or not. She ain't lak us, I know 'at much. Prowls the bayous at night; goes into places wit her pirogue where big men won go. Believes in the old ways; won turn loose.”

“She says the roo-garous are walking.”

Eddie lost his .temper. “Goddamnit, Jenny! There ain't no such creature as a roo-garou. Doc Lormand said Claude Bauterre had a disease. Can't pronounce the name of it. Don 'member it. Don wanna 'member it.”

“If old Claude Bauterre had a disease, and wasn't no roo-garou, how come you menâmy papa wit youâshoot the man more'un fifty time? Burn his body? Seal him in a steel box? Burry him in tree, four feet of cement?”

“ 'Cause we was stupid, Jenny! Me, you poppa, and the priest, too. We was clingin' to ways that never were true and ain't true now.” He shook her like a child. “Jenny, listen to me: there ain't no such ting as a gris-gris. No such ting as a spirit man that roams the bayous. And they ain't no such ting as a roo-garou.”

She stubbornly shook her head. “You said you seen him change from a beast, Eddie. You been lyin' to me all these years?”

“Non,

Jenny,” he said softly. He wanted desperately to believe his own words. “But Doc Lormand said sometimes men who have this disease can really look lak a beast. Jist lak Trahan's dog-boy! Act lak one, too. Claude Bauterre was sick in the body and in his head. And weâall of usâwas drinkin' at night. To hep our courage. Bauterreâor somebody,” he said, a sickness welling up within him. “had killed the sheriff and been prowlin' the bayous for years. Maybe kilt tree, four others, too. Can't be sure. But our . . . emotions was runnin' high and hot; makes men do and see funny tings. ”

Jenny,” he said softly. He wanted desperately to believe his own words. “But Doc Lormand said sometimes men who have this disease can really look lak a beast. Jist lak Trahan's dog-boy! Act lak one, too. Claude Bauterre was sick in the body and in his head. And weâall of usâwas drinkin' at night. To hep our courage. Bauterreâor somebody,” he said, a sickness welling up within him. “had killed the sheriff and been prowlin' the bayous for years. Maybe kilt tree, four others, too. Can't be sure. But our . . . emotions was runnin' high and hot; makes men do and see funny tings. ”

“I believe the priest, Eddie. Father Huval wasn't wrong. He said this has happen before, here and in other places, too. Maybe we oughtta talk to the priest, Eddie. Talk to young Father Huval. Maybe his cousin tell him someting 'bout what happen 'fore he died?”

Eddie shook his head. “Old Father Huval din tale his cousin nuttin 'bout that night and followin' day, Jenny. I know that.” He walked to the door.

“Where you goin', Eddie?”

“To pick up LeJeune and Bares. I got to see someting wit my eyes. After that, the tree of us will ride out to see 'bout your poppa.”

Eddie picked up Tony LeJeune and Frank Bares. They drove to Claude Bauterre's crypt. There, they all saw something. They looked in horror at something: Claude Bauterre's ashes were gone. The steel box that had contained them was broken open.

Other books

Duskfall by Christopher B. Husberg

Secrecy by Belva Plain

Play My Game by J. Kenner

Kill Me Softly by Sarah Cross

From Fake to Forever by Jennifer Shirk

Come Twilight by Tyler Dilts

The Smuggler and the Society Bride by Julia Justiss

¿Por qué leer los clásicos? by Italo Calvino

The Counterfeit Mistress by Madeline Hunter

The Saint in Europe by Leslie Charteris